This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The God Equation" by Michio Kaku. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Is string theory correct? Is it even possible to find out whether it is or not?

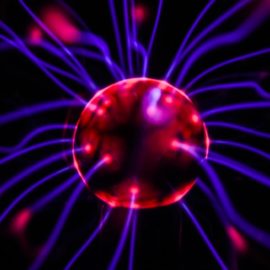

In The God Equation, theoretical physicist Michio Kaku suggests that string theory might be the path to uniting all the different laws of nature. But, many scientists reject string theory as a piece of mathematical sleight-of-hand.

Read more to learn about the fascinating debate surrounding string theory.

Investigating String Theory

Despite the encouraging direction string theory provides to theoretical physics, it hasn’t met with universal acceptance within the scientific community. The question “Is string theory correct?” might even be considered premature, as we don’t even know how to go about finding an answer. That’s right: The objections to string theory revolve around the fact that a scientific hypothesis has to be tested for it to be considered a viable theory, and, so far, string theory has failed to suggest even a method to test it. We’ll address these concerns and offer several potential avenues by which experimental data might confirm string theory’s claims.

Kaku says the most direct test of string theory would be to produce and observe a graviton to see if it conforms to string theory’s predictions. However, to observe a graviton with our current methods would require a particle accelerator the size of our whole solar system. Another facet of string theory that gives physicists pause is that string theory’s equations don’t allow for just a single universe but a potentially infinite multiverse. To this, Kaku replies that we don’t even have a final version of string theory’s equations as of yet. Perhaps there really is a multiverse out there, or maybe—whatever the true God Equation is—there’s only one viable solution with the others being too unstable to exist.

(Shortform note: The idea of a multiverse has become a staple of popular culture, in particular the Many Worlds Interpretation introduced by Hugh Everett in 1957. This approach to the quantum uncertainty problem suggests that every decision or random occurrence with more than one possible outcome produces one or more branching universes in which those outcomes took place. A different interpretation of the multiverse, the one that Kaku leans toward, suggests that other universes may exist in parallel, and completely separate from, our own. These other universes may have different laws of nature and particle interactions, such that most might be inimical to the development of life forms such as us.)

To the charge that we can’t directly test string theory, Kaku points out that science often tests its theories indirectly. One avenue might be through astrophysicists’ search for the unseen dark matter that permeates the universe. String theory predicts several options for what dark matter might actually be, such as microscopic black holes or particles called photinos. If any of these are eventually found, it would strengthen string theory’s overall standing. Another option comes from the recent discovery of gravity waves, as predicted by Einstein. Kaku writes that, if we can detect gravity waves generated by the Big Bang itself, they may confirm or deny string theory’s predictions about the nature of the universe’s origin.

(Shortform note: Progress has already been made to detect gravity waves. Kaku’s other two options may prove more difficult. Attempts to detect photinos in the 1980s and ’90s produced tantalizing hints but no actual results. A search for microscopic black holes in 2010 using the Large Hadron Collider likewise provided no evidence for their existence. A new avenue of approach that’s opened up is to use string theory to make predictions about the universe’s early inflation. If string theory suggests a solution to the question of what took place on the quantum level during that early epoch, then it may make predictions that can be confirmed via astronomy rather than looking at the subatomic scale.)

If we do find that string theory is correct, will it make a difference in our everyday lives? Kaku admits that it probably won’t—the energies involved in making use of string theory are orders of magnitude beyond what we possess. Its biggest impact might be felt in the circles of religion and philosophy. If one equation explains the entirety of the cosmos, it may change how we conceive of God and our place in the universe. Though Kaku describes himself as agnostic, he finds it amazing that all the laws of physics can be summarized succinctly and display such symmetry. For him, the mathematical beauty of the laws of physics opens the door to the possibility that there might actually be a grand design.

(Shortform note: While Kaku takes a cautious approach to linking string theory with the existence of God, others have openly embraced the idea. In Life After Death, Dinesh D’Souza argues that the multiverse interpretation of string theory opens the door, not only to God, but to the existence of heaven and hell beyond the bounds of our own universe. However, in The Trouble With Physics, Lee Smolin argues that, without experimental evidence, string theory has risen to the level of dogma, with many conjectures that must be accepted on faith. In other words, string theory may have stepped beyond science and become a quasi-religion unto itself.)

Exercise: Reflect on String Theory

String theory offers a mathematical resolution for the many incongruities between the laws governing the fundamental forces. Does its lack of experimental evidence make you doubt it, or do you believe that an elegant mathematical solution is persuasive on its own? Why do you feel one way or the other?

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Michio Kaku's "The God Equation" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The God Equation summary:

- The search for one theory that would unify all the rules of physics

- Why physicist Michio Kaku thinks string theory may hold the answer

- An explanation of string theory and the underlying symmetries of nature