This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Organized Mind" by Daniel J. Levitin. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How does attention work? How does your brain know what to focus on? Can you pay attention to more than one thing at a time?

Neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin explains the two modes of attention and how the brain chooses between them. He also argues that multitasking is impossible.

Continue reading to learn how attention works.

How Does Attention Work?

How does attention work? Levitin explains that we have two modes of attention: Our brains operate either in the “central executive” (CE) mode or the “mind-wandering” (MW) mode. CE mode is what you’re using to read this; it takes over when you’re trying to focus on a particular task. If you’re not in CE mode, your brain naturally reverts to MW mode: You’re not focused on anything in particular and are instead letting your thoughts flit among various topics.

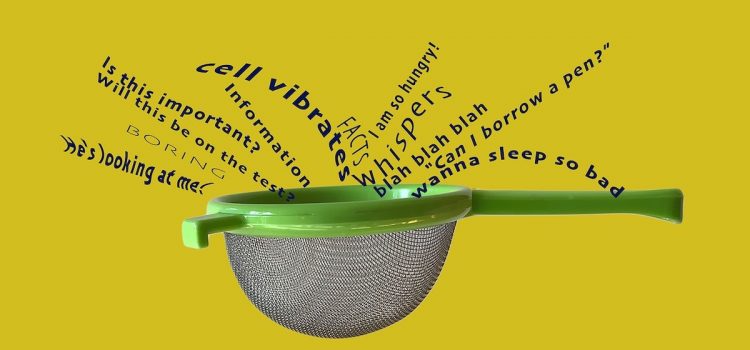

Levitin explains that your brain chooses your mode of attention using two mechanisms: the “attentional filter” and the “attentional switch.” Your attentional filter is a group of neurons that constantly assesses your environment and guards against unimportant information. But sometimes, your brain does decide that something is immediately relevant: In particular, it will do so if it detects something new or something significant. In that case, your attentional switch kicks in—and directs your attention to something else. (This can happen within or outside of your conscious awareness.)

For example, say you’re reading this guide in CE mode at a coffee shop. Your brain is registering countless stimuli—like the sound of the radiator and the smell of espresso—but your attentional filter is keeping it all at bay so that you can focus on reading. However, if you were to spill hot coffee on your pants, your attentional switch would alert you to the hot sensation (which is both new and important because it’s dangerous) so that you could jump up and clean it off. After that, you might decide to observe your fellow cafe-goers and relax for a few minutes—in which case you would consciously use your attentional switch to shift to MW mode.

(Shortform note: Levitin noted in a blog post that Donald Broadbent was one of the scientists who identified the “attentional filter.” This suggests that Levitin took the term from Broadbent’s filter model of attention, which was the first theory that posited that you filter out unimportant information so that you can pay attention to the things that matter. Additionally, Levitin is one of the few authors to use “attentional switch” to describe both the neural mechanism that redirects your attention and the process of redirecting your attention; other authors tend to use “attentional shifting” to describe the process of redirecting your attention.)

| How Switching Between The Brain’s Modes Helps You Solve Problems In A Mind for Numbers, Barbara Oakley also explains that your brain naturally alternates between two modes, but she calls them by different names. Focused-mode thinking is Levitin’s CE mode: It occurs when your attention is focused on something, and it allows you to process detailed information. Diffused-mode thinking is Levitin’s MW mode: It occurs when you relax your focus or let your mind wander. While Levitin focuses on how these two modes differ, Oakley, whose text is geared toward learning, focuses on how you can use these two modes in concert. Oakley explains that solving any difficult problem requires an exchange of information between these modes. So you should start by focusing on the problem, then deliberately divert your attention (for example, to exercising or doing routine tasks) so that your brain can switch to diffuse mode and approach the problem creatively. In other words, you must first employ your attentional filter to keep out irrelevant information so you can focus in CE mode, then deliberately use your attentional switch to move into MW mode. |

The reality of how attention works explains why multitasking doesn’t work. When faced with too many demands on your time, you may try to multitask. However, you’re incapable of multitasking: You may think you’re doing two things at once, but you’re actually alternating your focus between the two demands. This constant shifting takes a serious toll: It tires out your brain faster, which evidence suggests results in reduced mental abilities. Moreover, multitasking necessitates that you make several little decisions (like which task to focus on at any given moment)—and, as we discussed previously, the more decisions you make, the worse your ability to make them gets.

| When Multitasking Works Unlike Levitin, who argues against multitasking in all its forms, Hyperfocus author Chris Bailey suggests that you can easily perform some simple tasks simultaneously. Since these tasks take up so little attention, you’re able to focus on them simultaneously instead of shifting your attention, so you don’t get tired. This is especially true if these tasks are habitual tasks you perform in autopilot mode—which means you make minimal decisions about them, and thus you don’t tire yourself out. For example, if you perform your skincare regimen while listening to a podcast every night, you don’t need to decide when to apply lotion or turn on the podcast; you automatically turn on the podcast when you walk into the bathroom and reach for the lotion after you wash your face. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Daniel J. Levitin's "The Organized Mind" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Organized Mind summary:

- The key to living less stressfully in the modern world

- Why our current approach to dealing with stress doesn’t work

- Strategies for sorting and externalizing your thoughts, things, and relationships