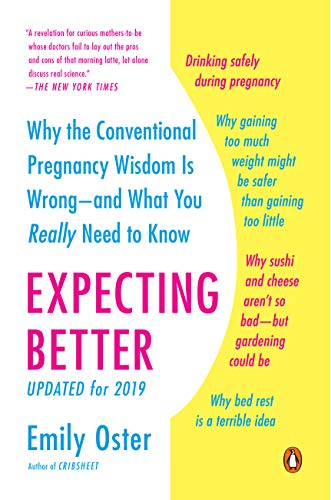

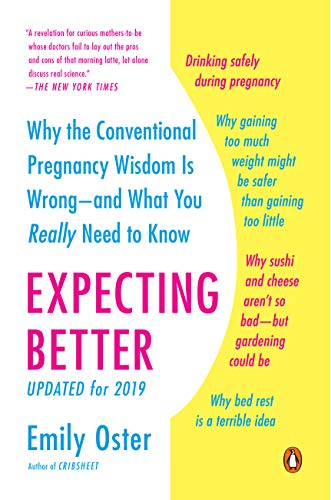

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Expecting Better" by Emily Oster. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Does it make sense for you to undergo genetic prenatal testing? What are the different ways you can do this, and what are their pros and cons? Learn the three methods of genetic testing here.

Why Do Prenatal Genetic Testing?

The primary purpose of prenatal screening during pregnancy is to detect chromosomal abnormalities, the most common being Down Syndrome, or trisomy 21. Tests also screen for the rarer Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) and Patau syndrome (trisomy 13), both more severe than Down Syndrome with babies rarely surviving their first year. Families at high risk for genetic disorders may also screen.

The risk of Down Syndrome increases with maternal age, from 1 in 1488 from ages 20-24, to 1 in 746 in ages 30-34, to 1 in 30 for age 45 (a fuller chart is shown later). For some comparison, the risk of a car accident in the next year is 1 in 50, and the risk of being audited in the next year is 1 in 200.

There are largely two types of screening: non-invasive (cell-free fetal DNA, ultrasound), and invasive (amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling). Non-invasive tests pose no risk to the fetus but are more prone to false positives and false negatives. In contrast, invasive tests have higher accuracy, but pose a risk of miscarriage (according to Oster, 1 in 800).

Spoiling the punchline: cell-free fetal DNA tests have advanced non-invasive screening considerably from the ultrasound days.

Plan Ahead Before Screening

Typically, people consider getting a non-invasive genetic screen first, then depending on the results, they might get an invasive genetic screen.

Before getting a screen, it’s useful to consider what you’re going to do based on the news you receive. For some parents, screening may have no point – no matter what they find, they’ll continue with the pregnancy. Then testing would just cause undue anxiety and may be unnecessary.

If you do want a genetic testing during pregnancy, then consider what you’ll do if you get a positive or negative result. For instance, if you get a non-invasive test and it comes back negative (things check out as normal), would you get an invasive test anyway to be sure? If so, then you might just skip to the invasive test anyway.

Noninvasive Test: Cell-free Fetal DNA

Cell-free fetal DNA tests use fetal DNA that is circulating in the mother’s bloodstream.

The mother’s bloodstream contains not just fetal cells but also fetal DNA outside of cells. In fact, 10-20% of DNA isolated from maternal plasma is from the fetus.

Theoretically, if the fetal DNA could be isolated fully from the mother’s DNA, then full genomic sequencing could occur. We’re not quite there yet, but bulk defects can still be detected – for instance, if a higher than expected proportion of chromosome 21 is in the mix, there’s a good chance it indicates trisomy 21.

The sensitivity (true positive rate, or accurate detection of a disorder) is remarkably high – in one large-scale study, 99.1% of trisomies are detected with this procedure. The false negative rate is also low, at 0.05% (of 146,000 women without Down Syndrome, 61 were given a false positive).

In essence, if you get a positive result, it’s very likely the child has Down Syndrome; and if it’s negative, it’s very unlikely the test is wrong.

If you get a positive result when you’re younger, the chances that the child actually has Down Syndrome are lower as well.

(Shortform note: the true positive rate increases with age because the risk increases a lot with age. When the baseline rate is high and the test is positive, chances are better that the test is correct, compared to younger mothers.)

Noninvasive Test: Ultrasound + Blood Test

The newer cell-free fetal DNA test may not be covered by insurance until you’re over 35. In contrast, the more traditional screen consists of an ultrasound to detect nuchal translucency (fluid behind the baby’s neck) and a blood test for hormones in maternal blood (PAPP-A, hCG).

This test’s accuracy is much worse than the cell-free DNA test – it detects only 90% of Down Syndrome cases (vs 99%), and it has a false positive rate of 6.3% (vs 0.05%).

An additional second trimester test draws blood and tests for alpha-fetoprotein, hCG, unconjugated estriol, and inhibin A. Combined altogether, the performance improves – up to 97% of Down Syndrome cases are successfully detected.

(Shortform note: the author doesn’t comment on the accuracy of combining the cell-free fetal DNA with the noninvasive test, but given the accuracy of the cell-free test, things may not improve by much.)

Invasive Test: CVS and Amniocentesis

Both invasive tests use a needle to extract something from the womb – in chorionic villi sampling (CVS) it’s part of the placenta; in amniocentesis, it’s amniotic fluid. CVS is performed earlier between 10-12 weeks, while amniocentesis is done between 16-20 weeks.

The accuracy of both tests is very high (Shortform note: the author doesn’t put numbers to this).

The risk of miscarriage is the worrisome part – inserting the needle might hit the fetus or pierce the placenta. Common wisdom puts the risk of miscarriage at 1 in 200.

Oster argues this number is outdated and based on research from the 1970s, which found a non-significant increase of miscarriages from 3.2% to 3.5%. With better procedures (using ultrasound to guide the needle), Oster believes the risk of miscarriage is now closer to 1 in 800, if there is any risk at all.

However, one factor may increase risk – the popularity of cell-free DNA testing has lowered the need for CVS, and practitioners may become rusty. So if you want to get invasive testing, go to someone who still does them often.

Making a Choice

Now equipped with this information about genetic testing during pregnancy, you can make a choice about risks and what you gain.

For instance, if you’re 35, get a cell-free DNA test, and receive a negative result, the baby’s risk of Down Syndrome is 1 in 45,109. The invasive test has a chance of miscarriage of 1 in 800. Do you think that the risk of unexpectedly having a Down Syndrome child is 56 times worse (45109 / 800) than having a miscarriage? If yes, then proceed to the invasive test.

For what it’s worth, Oster chose ultrasound screening for her first child at age 31. For her second child at age 35, she believed the risk of miscarriage was less important now that they already had one child, and she chose to have amniocentesis in the second trimester. As Oster stresses, this was her personal choice, not what she dictates for everyone.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Expecting Better" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Expecting Better summary :

- Why much parenting advice you hear is confusing or nonsense

- The most reliable way to conceive successfully

- How much alcohol research shows you can drink safely while pregnant (it's more than zero)

- The best foods to eat, and what foods you really should avoid