Take a journey through the southern US, West Africa, and the Middle East with Ta-Nehisi Coates. The Message is more than a travelogue; it’s his exploration of how stories shape our understanding of race, power, and oppression.

Coates believes that writing is more than just putting words on a page—it’s a way to challenge injustice and reclaim stolen narratives. Keep reading to explore what he discovered on his travels.

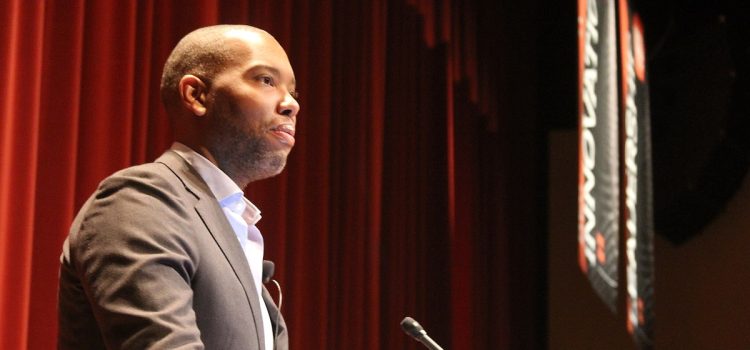

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons (License). Image cropped.

Overview of The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates

The 2024 book The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates weaves together a series of travelogues spanning visits to South Carolina, Senegal, and Palestine to explore how narratives about race and power shape our understanding of the world. He explains that he sees storytelling as an act of resistance, particularly for writers from historically marginalized groups who challenge systems of oppression through their work. By applying this perspective to cultural and political flashpoints in each of the places he visits, Coates presents The Message as both a personal journey and a testament to the power of writing.

In this overview of Coates’s book, we start by unpacking his love for storytelling and its power to challenge the American racial hierarchy. Then, we show how he brings that critical lens to his travels, starting with the West African nation of Senegal, where he grapples with the legacy of enslavement. From there, we travel with Coates to South Carolina, where he examines modern political battles over the teaching of American history. Finally, we follow Coates to Palestine, where he applies his insights on oppression and historical narrative to the Palestinian struggle.

Part 1: The Power of Storytelling

We’ll explore Coates’s impetus for writing The Message, looking at what he sees as the power of the written word to challenge racist narratives—and his desire to empower his students with that sense of purpose.

Why Coates Loves Storytelling

Coates says he became a writer because he loves the transformative power of language. He explains that narrative is what gives language power—it organizes words into stories that give meaning to the world’s events while imbuing people with agency and moral weight.

For example, by crafting a narrative about a young Black student who excels academically despite attending an underfunded school, a writer can transform cold statistics about educational inequality into a powerful story that reveals systemic injustice while showcasing human resilience and potential. The narrative moves beyond data to create emotional connection and moral clarity.

Coates’s Literary Mission

Coates says that, as a Black writer, he approaches his craft with a literary mission: He asserts that narratives can create great characters and produce powerful emotional responses, but they can also be used to reveal hard truths and give a voice to the voiceless. In a society that he says denies the full humanity of Black people and marginalizes their voices and experiences, telling stories and sharing experiences is a statement of Black humanity—and that is a political and revolutionary act in and of itself.

Coates also applies this mission to his teaching. He explains that as a writing professor at Howard University, the historically Black college he graduated from, teaching writing is about more than improving his students’ technical skills. It’s about empowering students to challenge the myths that marginalize communities of color, so they can transform words from tools of oppression into instruments of liberation and truth.

Why Coates Wrote The Message

It’s with this understanding of his mission as a writer that Coates dedicates his travel writings to his students. He presents them as a substitute for an overdue assignment—something he submits in lieu of an essay he promised he’d let them critique but which never materialized. He also notes that The Message is his contribution to the work of confronting injustice: The point of his travelogues is to help illuminate crucial truths about the world and Black humanity.

Part 2: The Journey Home: Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Journey to Africa

Now that we’ve discussed the reasons Coates wrote The Message, let’s turn to his travelogues. We’ll explore Coates’s observations and feelings from his journey to the West African nation of Senegal in the summer of 2023. To him, going to Africa wasn’t a vacation; it was a pilgrimage infused with deep meaning.

Coates explains that Senegal has become a founding myth to Black Americans, symbolizing the history of their ancestors’ enslavement. This is especially true of Senegal’s Gorée Island, with its famous House of Slaves (a museum that memorializes the export of enslaved Africans). Historians note that other locations in West Africa handled far greater numbers of enslaved people. But because of Senegal’s symbolic significance, Coates viewed it as a starting point to examine narratives about Black American identity.

During his journey through Senegal, Coates realized his perceptions of the country were shaped by the legacy of racist literature that minimized the humanity of African people. We’ll explore how Coates confronted those perceptions and look at what he learned during his trip to Gorée Island.

Coates’s Perceptions of Africa

Coates explains that the Western world’s ideas about Africa largely derive from the historical works of white racial propagandists who portrayed Africa as a backward land populated by uncivilized, superstitious, and simple-minded people. Coates says that by falsely portraying Black people as inherently inferior, enslavers and colonizers could justify subjugating them. It made their violence and economic exploitation seem natural and helped them maintain their moral self-image.

When Coates’s plane arrived in Dakar (the capital of Senegal), the first thing he saw was a beach strewn with what appeared to be discarded and abandoned exercise equipment. This presented him with a deeply unsettling thought: Were the white narratives of Black inferiority correct after all? He worried that this image represented the very worst stereotypes of Black Africans conjured by white-created mythology: an Africa marked by disorder, dysfunction, inefficiency, and poverty.

Finding Renewal

Coates writes that his initial feelings of unease about the city changed quickly. He discovered that amid the signs of poverty, there were also visible signs of beauty and renewal. Yes, he saw crumbling buildings, but he also saw people in perfectly tailored suits, as well as active construction sites for new, modern buildings. Dakar wasn’t some decaying ghost town, and Africa hadn’t shriveled and died after centuries of colonialism and depopulation through the slave trade. Coates also realized that his initial perception of disorder and chaos was false. The abandoned gym equipment wasn’t abandoned at all—it was being used as a community fitness space, available and open to everyone.

Examining His Own Myths

Coates recognized that he was engaging in myth-making of his own in thinking that African life and culture had been destroyed and left behind: that it was a static world forever rooted in its tragic past. In fact, Africa had survived and forged its own identity—separate from the Black American experience. The Senegalese people he met may have shared a historical connection to him, but Africa wasn’t his starting point or his origin story, nor did he have the right to claim it as such. The people there had created an identity and a story all their own.

The Social Construction of Race

Coates writes that as he ruminated on these historical and cultural legacies, Senegalese friends reminded him that race is socially constructed, not a biological reality. They told him that most Black Americans, including himself, would be seen as “mixed” in Senegal—not Black. This is because people’s racial identities fluctuate depending upon the historical era, geographical region, and socioeconomic circumstances in which they find themselves.

A Journey to Gorée Island

The emotional culmination of Coates’s journey to Senegal was his visit to Gorée, a small island just off Dakar. The Senegalese officials who maintain the memorials on the island claim that it was a major slave-trading center during the four centuries of the transatlantic slave trade, a site from which millions of Africans were forced onto ships bound for the Americas. However, Coates explains, research had proven that Gorée actually wasn’t a major point of departure for enslaved Africans—other locations trafficked more people. Regardless of that historical reality, visiting a place so fraught with emotional meaning moved Coates to tears.

This tension led Coates to a key insight: Even imagined traditions and places can hold legitimate power when we acknowledge their constructed nature. He argues that Black Americans have a right to consecrate symbolic sites like Gorée, but they’re also responsible for questioning historical myths. For Coates, sites like Gorée give meaning and purpose, and stand as both a beginning and an end point: a place where one people was eliminated and another was born. Thus, mythologizing Gorée is an act of a cultural creation by a people who wish to assert their own agency in telling their story—to reclaim an identity and a narrative that was stolen from them.

Part 3: A Classroom Under Fire in South Carolina

Now that we’ve discussed what Coates learned from Senegal, let’s turn to his visit to South Carolina. There, he visited a white high school teacher named Mary Wood, who’d assigned Coates’s book Between the World and Me to her English students. Her aim was to help them grasp racial injustice in America, but the assignment ignited a firestorm of controversy.

What Coates encountered in South Carolina was another reminder of the power of narrative. He recognized that the battle for how to reckon with America’s racial history wouldn’t be waged in the streets and or won with violence. Stories would be the true battleground. We’ll explore the controversy around the push to ban certain texts from classrooms, the struggle over American history, and how narratives and storytelling shape the limits of our moral and political imagination.

A Fight for Educational Freedom

Coates writes that Wood’s English class became a flashpoint when students complained that Between the World and Me made them feel bad about being white. In response, writes Coates, the local school board banned the teaching of what it believed to be “divisive” ideas or any that might cause students “discomfort.” Coates made the journey to South Carolina to support Wood at a school board meeting. Coates says he was heartened to see how many local residents turned up—many of them white Southerners deeply aware of their state’s racial history—to argue for Wood’s right to teach material that challenges traditional hierarchies.

History As a Battleground

Coates writes that the controversy he witnessed in South Carolina provided a window into how schools have turned into war zones over different ideas about America’s past. He writes that these school board hearings are about more than just which books get assigned on a curriculum. They’re about who gets to control the narrative of our past.

Coates argues that some Americans believe in a fundamentally benevolent vision of their country—they’re invested in a narrative that presents America as an exceptional, inherently just nation. Works of art and history that center Black voices can contradict that narrative by highlighting racist oppression. Confronted by these works, Americans who subscribe to the benevolent-nation narrative struggle to reconcile the gap between the evidence of oppression and what they want to believe. It’s often easier to resist or dismiss the evidence entirely, writes Coates—which is why books like his get banned.

Storytelling Shapes What’s Possible

Coates writes that the battle being waged over American history also affects the future. He explains that narratives don’t just depict life—they shape it by determining which experiences and perspectives are worth remembering and which aren’t. Writers, artists, and film creators all make choices about which voices to center, which experiences to validate, and which futures to envision—and these choices inevitably carry political weight. When we consistently see certain types of people as heroes, villains, or background characters, they shape our moral imagination by setting limits for what’s possible and what isn’t.

Coates writes that this is why white racial propagandists created their own corpus of art that affirmed their preferred narratives of white superiority and white people’s rightful place at the top of the hierarchy. This can be seen in films and novels of the 20th century that present the antebellum South as an idyllic place, downplaying the violence and exploitation at the heart of the plantation system. It can also be seen in contemporary works that present a “white savior” narrative, one that centers the heroism and decency of a white protagonist who helps Black people overcome racism and poverty—presenting Black characters as passive beings to be rescued, rather than having their own agency.

Meanwhile, stories that expand representation, challenge existing power structures, or imagine alternative ways of organizing society can begin to knock those mental barriers down. Coates writes that this is why authoritarians often target books and art. They understand that controlling the narrative, authoring the story, and shaping the limits of possibility are their most powerful weapons.

Part 4: Confronting Zionism and Historical Erasure

We’ll explore Coates’s experiences in Palestine—the Israeli-occupied territory on the West Bank of the Jordan River. We’ll look first at Coates’s analysis of Israel’s founding myth—a narrative that situates the nation as a safe haven for Jews established after the Holocaust. Then, we’ll explain why Coates believes Israel has itself become an oppressor in its treatment of the Palestinians, and we’ll explore what he sees as parallels between the Palestinian struggle and that of Black Americans. Finally, we’ll discuss Coates’s argument about the importance of elevating Palestinian narratives.

Oppression and Renewal: The Origins of the State of Israel

In Jerusalem, Coates visited the Yad Vashem memorial, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It tells the story of the near-destruction of the Jews of Europe through personal artifacts and survivor testimonies—creating not just a chronological narrative of the Holocaust, but conveying to visitors the profound weight of loss, the imperative of remembrance, and the enduring meaning of each individual life that was destroyed.

Coates describes being deeply impacted as he sees the Hall of Names, which lists the millions killed. While certainly aware of the Holocaust as a historical event, Coates found it hard to grasp tragedy at this scale as he came face to face with the sheer gravity and enormity of the atrocity.

Coates writes that the enormity of the Holocaust has become a foundational story for Israel—not merely as historical backdrop, but as the defining narrative that shapes its national identity and purpose. Just as he observes about America, Coates writes that Israel’s foundational story weaves a narrative about the nation and its people that places it firmly on the side of justice and truth. In this telling, the Jewish people rose from the literal ashes of the death camps to reclaim their own story and carve a democracy out of hostile terrain.

The Oppression of the Palestinians

Coates writes that Israel sees itself as the national homeland for a people who’ve endured millennia of oppression. However, during his ten days traveling through occupied Palestine, he came to believe that Israel was itself engaged in the brutal oppression of Palestinian people. He also saw parallels between Israel’s oppression of Palestine and the historical subjugation of Black people in the US.

A Modern-Day Colonial State

Coates sees Israel as an apartheid state. For him, Israel is a country in which the dominant ethnocultural group—Jewish Israelis—are given full rights of participation in a healthy democracy and are protected by the rule of law. On the other hand, he notes, Arab and Muslim Israelis (that is, Palestinians) are excluded from full participation in the country’s civic life, are subject to intimidation and harassment by the authorities, and have been economically marginalized. Daily life for Palestinians, Coates observes, is an ordeal of constant surveillance and control as they contend with regular military checkpoints and house searches that Jewish settlers aren’t subjected to.

Going further, Coates describes how he came to see Israel as a colonial project designed to extend Israeli political and economic dominance over the occupied territories. He points to how Israel makes it cheaper and easier for Jewish citizens to move to West Bank settlements, using things like housing discounts and better funding for schools and infrastructure. In contrast, writes Coates, Palestinians face a maze of permit requirements for basic construction, with most applications rejected. They’re often blocked from accessing farmland and natural resources, which get redirected to Israeli use instead. As a result, Israeli settlers maintain control over Palestinian land, which aligns with common definitions of colonialism.

Historical Parallels With Jim Crow

To Coates, Israel’s treatment of Palestine is reminiscent of the Jim Crow South, the system of state and local laws that enforced racial segregation and political disenfranchisement against Black Americans in the Southern US. He finds this connection reflected in the language Palestinian activists use in attempting to create their own story of subjugation, loss, and attempted renewal. His Palestinian friends and guides evoked writers from the canon of Black liberation—James Baldwin, Angela Davis, and even himself. In hearing this, Coates writes that he felt a sense of kinship with his Palestinian companions, a solidarity between historically oppressed peoples.

The Way Forward: Elevating Palestinian History and Voices

After exploring Israel’s subjugation of Palestinian people, Coates turns his attention to the way forward. He argues that for Palestine to be liberated, the world must hear directly from Palestinians because, as we’ve explored, narrative control represents one of the most fundamental aspects of power and oppression.

Historically, Israeli, American, and European authorities have controlled the Palestinian narrative. For example, Coates points to Israeli historical projects like the City of David, an archaeological site and national park that, he says, distorts ancient history to justify Israeli claims to Palestinian land. According to Coates, officials at the site selectively curate the artifacts and their presentation to visitors to advance a narrative of unbroken Jewish historical connection to the land—while minimizing other historical periods and cultures, particularly those of Palestinian, Byzantine, and Islamic heritage.

Coates adds that narrative control extends into media coverage of Israeli-Palestine relations. For Palestinians, decades of having their experiences filtered through Israeli, American, and European media have resulted in their systematic dehumanization and the erasure of their historical claims to land and dignity. Thus, writes Coates, Palestinian storytelling becomes an act of resistance against narrative colonization—just as it is for Black Americans. When Palestinians speak for themselves, they cease being objects of political discourse (who are passive and acted upon) and become human beings who act with agency.