This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Singularity Is Near" by Ray Kurzweil. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What are designer drugs? Can DNA rewrite itself? What if we could grow our own replacement organs?

In The Singularity Is Near, Ray Kurzweil makes predictions about technology in several areas. One field he addresses is biotechnology, in which advances in medicine and genetic engineering will dramatically extend the human lifespan while at the same time improving the quality of life.

Continue reading to learn about Kurzweil’s predictions about the biotechnology revolution and where progress actually stands today.

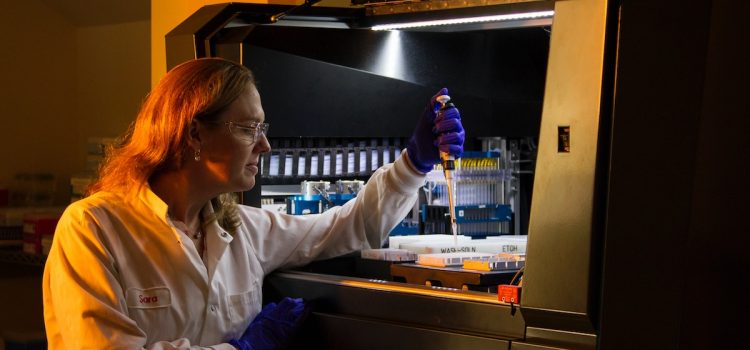

The Biotechnology Revolution

Kurzweil identifies three principal areas of technological advancement that he says will have the greatest impact on the world to come. The first of these is biotechnology. Here, we’ll explore the trends in the biotechnology revolution that Kurzweil highlights as the most intriguing—the use of genetics to create designer drugs, the progress toward rewriting DNA itself, and the potential to grow your own replacement organs by repurposing other cells in your body.

The first of these trends involves our ability to chase immortality via preventative maintenance on our bodies. This is already possible to some extent through the use of exercise, diet, and supplements. Kurzweil suggests that, the more we learn about DNA, the more we’re able to enhance this ability through the creation of bespoke disease-fighting medication that’s tailored to the specific genetic code of an individual. As opposed to broad-ranging chemical medications with their array of unwanted side effects, treatments tailored to a person’s genetic code can maximize the body’s defenses, combating disease and even turning back aging.

(Shortform note: In Lifespan, geneticist David Sinclair agrees with Kurzweil that aging is a treatable condition. Sinclair argues that aging is caused by a breakdown of the proteins that determine which genes are turned on or off. As a solution, Sinclair highlights approaches that can eliminate cells that no longer reproduce, identify genetic risk factors for disease long before their symptoms appear, repair the enzymes responsible for healthy genetic function, and reset your body’s biological clock. If medical science continues to advance at an accelerating rate, then all of these options become steadily more viable, and the people who live longer as a result will have an increased stake in safeguarding the future.)

Beyond targeting medication for individuals’ genetics, Kurzweil says that our ability to affect genes themselves is accelerating. The ultimate aim of this line of progress is to inject new DNA into the nucleus of the cell. This would let us replace damaged genes with healthy ones, eliminating genetic diseases and even introducing new genetic abilities, supplanting evolution by random mutations with human-designed, beneficial DNA. Kurzweil acknowledges that the main hurdle of gene manipulation is getting the altered genetic code past the cell’s natural defenses. If this can be accomplished, we could eliminate cancers, rid the body of toxins, and put a halt to the mitochondrial mutations that drive the aging process and eventually lead to death.

(Shortform note: Since the time of Kurzweil’s writing, geneticists have devised new, advanced methods of editing genes using CRISPR—Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats—to target and repair damaged DNA. CRISPR’s relative ease of use has sparked a new round of ethical debate regarding genetic manipulation. Concerns revolve around the safety of the process and whether gene therapy will be available to all or merely the super-rich. The possibility of using CRISPR to rewrite the genome of human embryos raises the question of consent regarding altered DNA that may be passed along to future generations.)

| Your Two DNAs Though Kurzweil discusses the difficulties of slipping engineered DNA around the cell’s barriers, those defenses evolved for a reason. In The Vital Question, biologist Nick Lane explains that the cells of all complex life forms descended from a hybrid of two separate orders of single-celled life. As a result, we have two sets of DNA—the DNA found in the nucleus, which contains the blueprints for our bodies, and that of the mitochondria, which generate energy for cells to function. According to Lane, the wall of the nucleus evolved to keep these two sets of DNA segregated. Furthermore, mitochondrial DNA reproduces much faster than nuclear DNA, meaning that it mutates and degrades much more quickly. Therefore, to achieve Kurzweil’s dream of halting the body’s natural decay, it may be just as important—if not more so—to address mitochondrial mutations rather than faults in our nuclear genetic code. |

The third path of research that Kurzweil writes about is in the replacement of sick and damaged organs. At present, this requires an organ donor and a risky surgical procedure. But, what if your body could be instructed to grow its own replacement parts? A potential avenue for this branches out from research into human cloning (which, in itself, Kurzweil finds ethically questionable). The breakthrough may come in a way to not only clone individual cells, but to reprogram them to serve other functions. Skin cells could be used to grow a new liver or kidney without running the risk of organ rejection, since the replacements would be from your own body and therefore already biologically compatible with the rest of your internal systems.

(Shortform note: Rather than cloning your own body’s cells to produce replacement organs as Kurzweil suggests, researchers have made progress in using stem cells from pigs to grow organs that could be used for human transplants. This potentially sidesteps concerns about extracting stem cells from human embryos for organ cloning. Meanwhile, as recently as 2018, researchers using CRISPR technology have made advances in repurposing human skin cells into stem cells, while the tech startup company Renewal Bio is working to create synthetic embryos as a means for growing new organs.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ray Kurzweil's "The Singularity Is Near" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Singularity Is Near summary:

- The upcoming technological shift that will change everything

- The revolutions in bioscience, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence

- How Kurzweil's predictions held up over time