What childhood experiences shaped Bill Gates into the tech visionary we know today? How did a rebellious middle child from Seattle end up founding one of the world’s most influential technology companies?

Bill Gates’s Source Code: My Beginnings reveals these formative moments. The book traces his journey from an energetic troublemaker to a pioneering entrepreneur. Gates shares stories about family influences, early computer encounters, and the friendships that changed everything.

Continue reading for an overview of this autobiography.

Image credit: shannonpatrick17 (License)

Overview of Bill Gates’s Source Code: My Beginnings

Bill Gates is renowned as a businessman, software developer, and pioneer of the computer revolution. At age 19, he founded Microsoft, which he would build into one of the world’s largest tech companies. Products based on software Gates designed now run on most of the world’s home computers, as well as many business and government systems. Since stepping back from Microsoft, Gates has focused on philanthropic efforts to improve global health, reduce poverty, and develop clean energy solutions to the problem of climate change.

But how did Gates become the man he is today? What experiences led him to be in the right place at the right time with the right set of skills to stake his first claim on the home computing landscape? In Bill Gates’s Source Code: My Beginnings, published in 2025, he seeks to answer those questions himself. In his first autobiography (with two more in the works at the time of publication), Gates describes his formative years, from his childhood in Seattle to the founding of Microsoft. In it, he reflects on the people, events, and sheer good fortune that gave him the opportunity to become a key figure in the computing world at such an early age.

In this overview of Source Code: My Beginnings, we’ll trace Gates’s life from his early childhood to his initial encounter with computers and his first high school business ventures, followed by his Harvard years and the events that led to the founding of Microsoft.

Starting Out (1955-1960)

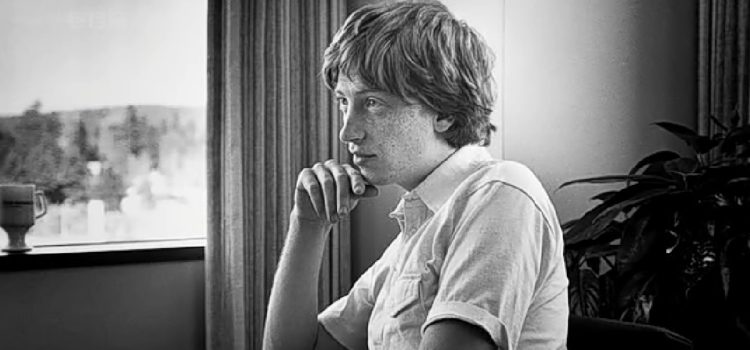

William Gates III, known to his family as “Trey” and only much later as “Bill,” was born in Seattle, Washington on October 28, 1955. Gates says this was the first stroke of luck—he was born into an era of abundance, progress, and excitement for the future. To be raised in a white, middle-class family in Seattle in the 1950s and ’60s was to be surrounded by upwardly mobile professionals of every stripe—doctors, lawyers, engineers—as well as to be immersed in a culture of technological advancement (Seattle was home to the aircraft manufacturer Boeing). While all this certainly left a mark on Gates, his outlook on life would also be shaped by his parents and his maternal grandmother, whom he called “Gami.”

Gates writes that his father, William Gates Jr., had a strong, confident, and even-tempered demeanor that suited his career as an attorney. Gates’s father instilled in him an appreciation for fairness and calm deliberation when confronted with life’s problems. At several points in Gates’s developmental years, as we’ll see later in this guide, his father would intercede when navigating a difficult situation required a steady hand. At home, Gates’s father served as the bedrock for the family, supporting not just Gates and his siblings, but also Gates’s mother in her social ambitions and philanthropic endeavors.

Gates’s Maternal Figures

Gates’s mother, Mary Maxwell Gates, came from a prosperous family with a culture of self-improvement established by her banker grandfather. From his mother, Gates learned the importance of ambition and setting high expectations for oneself. In a time when many women remained in homemaker roles, Gates’s mother became active in social organizations and community service groups. She widened her family’s social connections and exposed her children to a plethora of adult role models, while also running an efficient household. According to Gates, his mother also taught him that people as privileged as they were (with a steady income and strong social ties) had a responsibility to use their resources to benefit others.

As much as his parents set examples for him, it was with his grandmother, Adelle “Gami” Thompson, that Gates had the most fun. She taught him the joy of reading when he was young, but Gami was also an expert card player. Young Gates found it amazing how easily she won every game, and at first he couldn’t understand her luck. Eventually, though, he realized it wasn’t luck at all—she was using her brain to track each card in play and calculate the odds of every winning hand. Gates writes that thanks to his grandmother, he learned that complex problems can be solved through careful observation and analysis. After catching on, he was finally able to match her at cards, proving to himself that any skill can be learned.

Growing Pains (1961-1967)

Despite the strong examples set by his family members, Gates admits that he sometimes exhausted them. Gates was the “middle child” between two sisters, and he admits to being the most frustrating of his siblings from his parents’ point of view—his older sister Kristi was an academic high achiever who played by the rules, while his younger sister Libby was the most outgoing and athletic of the three. Gates describes himself as having been energetic, intense, single-minded, and often rebellious as a young child. In this section, we’ll describe his troubles fitting in at school, his conflicts with other family members, and how these problems reached a breaking point before he was 12 years old.

From the start, Gates wasn’t a typical student. He was younger and smaller than other children in his grade, and he had a habit of rocking back and forth when concentrating. Gates suspects that were he a child today, he’d have been diagnosed as autistic. As it was, his classmates just saw him as an oddball. He developed an early aptitude for math and reading, neither of which were considered “normal” for boys. Early on, he learned to compensate by using his energetic personality to take on the role of “class clown.” Meanwhile, he’d obsess over projects that intrigued him, but he had a hard time caring about any subject he wasn’t interested in, and his grades suffered as a result.

Gates’s Youthful Rebellion

Gates recalls that by age nine, he was openly questioning adult authority. He argued with teachers about rules he didn’t agree with, and at home he’d regularly butt heads with his parents. In particular, he locked horns with his mother, whom he perceived as trying to control him by means of her many expectations. Gates wanted the independence to pursue his interests and ignore everything else, while his mother tried to push him toward extracurricular activities, social opportunities, and behavior that was more in line with what she believed was normal for boys his age, such as sports and playing in the school band. One activity he did like was hiking, which gave him a degree of independence, at least as long as the hikes lasted.

As Gates’s conflicts at school and at home grew worse, his parents turned to a therapist, Dr. Charles Cressey, for help. Gates attended therapy for two years, in which he explored his conflict with his parents. He writes that in the end, Cressey’s conclusions and advice were both helpful and surprising. Cressey told both Gates and his parents that in their ongoing power struggle, Gates would eventually come out on top. To his parents, this meant accepting that he was different and giving him leeway to explore who he was. To Gates, Cressey recommended that he stop treating his parents as antagonists and instead cultivate them as allies for the future. After all, they loved and supported him, and it was foolish to sour that relationship.

Introduction to Computers (1968-1971)

Gates’s newfound truce with his parents coincided with another major change in his life—in 7th grade he began attending Lakeside School, a private educational institution that his parents felt would give him the challenges he needed. Gates says that this was a massive stroke of luck, because in 1968, a year after he enrolled, Lakeside School acquired its first computer terminal, where Gates learned the skills that would shape the rest of his life. Gates describes his first experiments with computing, his first opportunities to put his skills to use, and how he and his Lakeside friends formed their first computer business.

Lakeside’s terminal was a teletype machine connected by phone to a computer in California, which the school had access to via a limited time-sharing system. Gates writes that the computer was an educational experiment, but none of the faculty knew how to use it. Thankfully, researchers had recently developed a programming language they dubbed “BASIC,” which Gates and his classmates were able to use to create their first, extremely simple programs, such as rudimentary calculators and a tic-tac-toe game. Once the school’s initial excitement wore off, a core group of computer enthusiasts (which included Gates) took shape and competed among themselves to see who could write the best code.

Gates’s First Coding Jobs

One of Lakeside’s computer enthusiasts was Gates’s older classmate Paul Allen—who would one day join him as cofounder of Microsoft. Gates recounts that Allen would frequently push him to stretch his programming skills. This came in handy when a local business gave Lakeside students free access to an even more powerful computer in return for testing their system for errors. Gates, Allen, and several other friends began spending all of their free time at this business, honing their skills and learning to solve problems. While it lasted, this experience was invaluable for Gates, who would often get lost in a trance of total focus. He also made connections with adult software developers, who provided expertise that the school didn’t have.

In a search for more computer access, Lakeside School contracted with another local computer timeshare company. Separately, Gates and his friends contacted this company under the name “Lakeside Programming Group” and got a contract to write a payroll program for a pipe organ manufacturer. This payroll program was Gates’s first business project as a software developer. It was also his first experience of the stressful dynamics and personality clashes inherent in working with others. Tensions developed between the older students on the team, including Allen, and the younger programmers, including Gates. Nevertheless, they finished the project, delivering a functioning payroll system to be used by a real-world business.

Tragedy and Growth (1972)

As much as being introduced to computers shaped his life’s trajectory, Gates’s future was influenced by his childhood friendships, both with Paul Allen and with another young man named Kent Evans. Gates and Evans befriended each other in 8th grade, and Gates frequently joined Evans’s family on weekend and summer excursions. Unlike most of Gates’s peers, Evans was passionate about his interests, especially national politics, and had a vision for achieving success as an adult. The Lakeside Programming Group discussed earlier was his brainchild, and according to Gates, it was Evans’s intensity that prompted him to think about his own long-term plans.

Gates and Evans’s friendship was cut short by Evans’s untimely death in a mountaineering accident in May, 1972. This occurred shortly after two of Gates’s teachers died in an airplane crash. Gates writes that this confluence of tragedies, but Evans’s death in particular, marked a moment of transition in his life. Had Evans lived, they’d have probably gone to college together and remained close friends (or even business partners) for the rest of their lives. However, even in his grief, he was struck by how strongly Evans’s death affected others. To cope with his loss and navigate a world that no longer contained his best friend, Gates resolved to continue the extracurricular coding work he and Evans had started together.

Continuing the programming group’s work wasn’t something Gates could do by himself, so he reenlisted his friend Paul Allen, who was now attending Washington State University. Working together helped Gates and Allen grieve, and it also rekindled the bonds of their friendship. Gates recalls that he came to appreciate how his and Allen’s different personalities balanced and complemented each other—Gates was frenetic whereas Allen was calm and patient. Gates was obsessed with the software they were writing, while Allen showed an interest in the computer hardware it ran on. This opened Gates’s eyes to ongoing advances in microprocessors that would present them with great opportunities several years down the road.

College Life (1973-1974)

Because of his family’s high expectations, there was never any doubt that Gates would go to college. He applied to top-tier universities and was accepted to Princeton, Harvard, and Yale. Gates writes that Harvard was always his top choice, so after his final summer in Seattle, he moved to Boston for the next stage of his life—which he thought meant pursuing an academic career in advanced mathematics. Harvard opened a world of opportunities for Gates, especially in the growing field of computers, but college life and Gates’s frenetic personality clashed in ways he hadn’t counted on.

Gates says that one of Harvard’s main draws was its Aiken Computer Laboratory, which he visited soon after starting college. The lab was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) for the benefit of Harvard’s engineering program, and though undergraduates weren’t usually admitted, Gates lobbied for—and received—access. In addition to housing a powerful computer of its own, the Aiken Lab had access to ARPANET, the computer network that would eventually grow into the modern internet. Once granted admission, Gates spent nearly all his free time at the Aiken Lab, where he worked on his own coding projects side-by-side with graduate students.

Gates Burns Himself Out

Despite Gates’s enthusiasm for college—or perhaps because of it—the realities of campus life began to wear on him mentally and physically. Gates admits that many of his troubles at school were the fault of his attitude and approach to education, which were at odds with the rigor and discipline required to succeed in an academic setting. Bored with the courses he was required to take, Gates would skip classes for an entire semester, then cram for the final exams at the end. He did this so he could sit in on classes that did interest him, as well as to free up more time for computing. However, the result was weeks of extreme stress as he tried to make up for lost time, and his grades suffered greatly despite his last-ditch efforts.

According to Gates, the biggest emotional blow Harvard dealt him was learning that he wasn’t the best and the brightest. Gates’s whole self-image had been based on being the smartest in his class, if not his whole school, but at Harvard, everyone had that background. As such, Gates struggled with finding a new role. At first, he’d hoped to pursue pure mathematics, but he hit a barrier when he realized he couldn’t crack the particular way of thinking that only the top mathematicians possessed. As he started feeling lost and his grades continued sliding, his body began to give out as well. The junk food, lack of sleep, and nonstop anxiety of making up for all his missed coursework took their toll, eventually landing Gates in the hospital.

A New Direction (1975)

At about this time, Gates began to seriously consider the computer industry, not academia, as his career path of choice. He’d kept in touch with Paul Allen, who joined him in Boston that summer to start his own career in computing. Together, they were at the right stage in their lives to capitalize on a computing revolution that was going to ignite later that very year.

Gates says that the revolution began when the Altair home computer was released in 1975. Whereas the computers Gates had spent his life programming were behemoths accessed via remote terminals, the Altair was the first home computer with any real processing power. It wasn’t much like the home computers of today—it came as a disassembled kit, it lacked a keyboard or monitor, and programs had to be keyed in manually using a back-and-forth toggle switch for ones and zeros. Nevertheless, Gates recognized its potential. Computer processors had been becoming smaller and more powerful, so a computer that would fit on a desk had been inevitable. All he and Allen needed now was a way to make such devices user-friendly.

“Micro-Soft” Is Born

Gates believed the answer to the Altair’s usability issue was in software, not hardware. When he’d first learned to code, he’d done so using the programming language BASIC. Now, Gates and Allen hit upon the idea of adapting BASIC to run on the Altair, which would let home users input programs more easily. In 1975, they named their business partnership “Micro-Soft” (for “microcomputer software”) and sent their proposal to MITS, the makers of the Altair. MITS responded that Gates and Allen weren’t the only ones with that idea, but whoever was able to develop Altair BASIC first would win the contract for software licensing rights. At once, Gates put his academic work on hold—he and Allen had a mission, and speed was of the essence.

To put their plan in motion, Gates and Allen used Harvard’s Aiken lab to write their software. Allen designed a system by which Harvard’s computer would mimic the Altair’s processor, while Gates wrote the code for BASIC that it would run. While effective, this ran afoul of Harvard’s rules regarding use of their hardware. Gates recalls that universities at that time hadn’t yet considered the possibility of students writing commercial code on their computers. Gates was cited for his excessive amount of computer time, as well as for letting unauthorized people (such as Allen) into the restricted lab. He was threatened with expulsion, but in the end he was merely reprimanded, and Harvard tightened their rules on lab use.

Gates Launches His Career (1975-1978)

Despite their troubles at Harvard, Gates and Allen were able to complete a prototype of BASIC for the Altair. Between semesters in 1975, they left Boston to set up shop in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where MITS was headquartered. Little did Gates know at the time, but his life had just changed direction. Over the next two years, he’d play a leading role in the birth of the home computer industry, clashing with both the computer hobbyist culture and the owners of MITS before turning Microsoft into the leading software-driven company of the computer revolution.

Gates writes that when he and Allen arrived in Albuquerque, they learned that MITS had vastly underestimated the demand for their Altair computer. Instead of the hundreds of orders they’d expected, thousands of computer enthusiasts wanted one, even without an easy way to input programs. Gates and Allen sold MITS exclusive worldwide rights to their BASIC software for the Altair’s processor for an initial fee of $3,000 plus royalties for each copy of their software MITS sold. Gates and Allen agreed to a 60/40 split of the proceeds, with Gates receiving the larger share, since he’d been the one most responsible for the coding.

As a software company, Micro-Soft’s first hurdle was to convince computer hobbyists that software was something they should pay for. Gates explains that in the ’70s, the computer industry revolved around hardware—software was treated as an afterthought, and many computer enthusiasts believed that it should be traded and passed around for free. Even before their deal with MITS was final, someone in California’s Homebrew Computer Club stole a copy of Gates’s BASIC prototype and shared it with others in their community. The theft and proliferation of free copies of his software stung Gates so badly that in 1976 he published an article lambasting the hobbyist community for piracy, triggering a debate over free software.

The Age of Microsoft Begins

Newly registered in New Mexico as “Microsoft,” Gates and Allen set up shop in Albuquerque, hired their first staff, and began producing software. Though MITS was their initial client, Gates knew that other, better-funded businesses would eventually dominate the computer market, so he began work on BASIC and other programming languages that would operate on different computer systems. However, since MITS owned the distribution rights to Gates’s BASIC, all outside client contracts had to go through them, and Gates recalls that MITS soon became delinquent in paying Microsoft the royalties it was owed. Gates returned to Harvard, but his main concern remained the future of his and Allen’s business.

In January 1977, it became clear to Gates that MITS was holding Microsoft back. Texas Instruments, Commodore, and later Apple were all expressing interest in acquiring Gates’s BASIC for their new computer systems, but MITS was in the process of being bought out and showed no interest in fulfilling its contractual obligation to actively market and license their software. Gates went on leave from Harvard (to which he’d never return), and working with legal advice from his father, Microsoft took MITS into arbitration to settle their dispute. Microsoft won: The judgment ended MITS’s rights to BASIC and confirmed that Gates and Allen owned the software’s original source code, which they were now free to license as they pleased.

Gates writes that Microsoft broke free from MITS just in the nick of time—1977 was the year that the home computer market exploded, and Microsoft was primed to make the most of its potential. That fall, three affordable, groundbreaking home computers hit the market: the Apple II, the Commodore PET, and Tandy’s TRS-80, collectively referred to as the “1977 Trinity.” Each of these systems came with their own version of Microsoft’s BASIC, with which hundreds of thousands of users could now write their own computer programs. In early 1978, since they were no longer bound as a contractor to MITS, Gates relocated Microsoft to his hometown of Seattle, where the next chapter of his life and business was about to begin.

Reflections on Identity

Gates concludes with his departure from New Mexico and his hopeful visions of the future from that time. Throughout his memoir, he meditates on the various ways his past shaped him, including the many roles and identities he took on in his formative years. In conclusion, let’s recap how Gates’s sense of himself and his potential transitioned over time.

From the start, Gates knew he wasn’t the same as his other classmates. In elementary school, he recalls being surrounded by others who were richer, taller, more athletic, or simply cooler than he was, so in his early days, he adopted humor as what set him apart and took on the role of “class clown.” He found that this identity served him well in terms of popularity, since he could be liked for being willing to crack jokes without having to compete with more popular students on their own terms. However, this identity didn’t serve him forever. When he transferred to Lakeside School, his joking ways worked against him in the more serious, academic-minded environment and his academic performance took a hit.

However, he recalls that during his hiking trips—the ones he started going on in his rebellious phase—he found that others looked up to him for his toughness, determination, and his problem-solving skills. Because of this, Gates writes that his outdoor activities gave him a taste of what it meant to be seen as a leader. Even though he wasn’t traditionally athletic in a way that would have made him stand out at school, when going on wilderness trips with his friends, his other attributes were more valuable.

Personal Roles Are Multiple-Choice

Gates recalls that during the time when his grades started slipping at school but he found himself blossoming on his hiking trips, he realized that “identity” is context-specific—one person can fill a multitude of roles depending on the situation and the people he’s with. This insight would serve him well going forward as he started to learn to craft his identity to suit whatever challenge or environment he was in.

The idea of playing multiple roles is something Gates first put to use at Lakeside, where he took on the personas of “smart kid,” “jokester,” and “leader” all at once, depending on whether he was interacting with teachers, hanging out with friends, or taking part in the burgeoning computer group. He recalls sometimes taking deliberate steps to keep his identities separate. For example, his grades improved when he reapplied himself and started taking his studies seriously, but since (as stated earlier) being “smart” wasn’t cool for boys, he arranged to own two separate sets of textbooks—one for school and one to study at home—so no one at school would see him study hard, maintaining the illusion that he wasn’t a nerdy bookworm.

Identity Into Adulthood

Gates would learn that identities change over time, though they all would contribute to his growth. As mentioned earlier, in his Harvard years, Gates’s “smart kid” identity took a hit when that trait no longer distinguished him from others. However, he writes that the particular way he was smart—being willing to push boundaries, question norms, and break rules—still helped him stand out and created opportunities that were normally reserved for more advanced students.

In particular, the intellectual enthusiasm that fueled his academic drive and his determination to find his own path (first expressed in his youthful hiking trips) coalesced to spark a new identity for Gates: that of a business founder and entrepreneur. This identity had started to grow at Lakeside school during his first ventures with Kent Evans and Paul Allen. As he transitioned from Harvard to Microsoft, this new identity would define his future. At the end of his memoir, there were several other identities that Gates had yet to assume: tech giant, business mogul, family man, and philanthropist. But that, as they say, is another story.