What is Verbal Judo? Why should you practice it?

George Thompson contends that, by using a form of “tactical communication” inspired by the Japanese martial art of judo, you can resolve stressful confrontations without losing your cool. Verbal Judo involves directing the other person’s energy toward a solution that makes everyone feel understood.

Read more to learn what Verbal Judo is and how it can improve your communication and relationships.

What Is Verbal Judo?

What is Verbal Judo? It’s a practical method for responding effectively to confrontations, arguments, and conflicts. We all encounter conflict at work, home, school, and elsewhere in our lives. Thompson contends that how you respond in a tense situation can determine the outcome: Either it’ll strengthen your relationships and help you find a resolution that satisfies everyone involved, or it’ll undermine your efforts to solve the problem and leave you or the other person feeling frustrated, misunderstood, and resentful.

(Shortform note: While many of us prefer to avoid conflict, some experts see disagreement as a crucial tool for improving our knowledge. Conflicted author Ian Leslie explains that cognitive flaws like confirmation bias make us think we’re always right, so our reasoning skills often don’t help us figure out what’s true. Instead, these skills seem to have developed to help us argue more effectively, according to evolutionary psychologists. Leslie points out that when we disagree, we think of arguments to prove to the other person that we’re right. This means that when we disagree productively, we can come to better informed, more intelligent, more insightful conclusions together—even if it takes some arguing to get there.)

If you’re like most people, you don’t always know how to behave when you’re under pressure. And Thompson explains that we naturally handle conflict reactively rather than responsively. When you react to a situation, you act in the heat of the moment. You might get defensive, take things personally, or attack the other person like you feel they’re attacking you. But when you instead respond to a situation, you give yourself the perspective to act in a more intentional and measured way—one that’s much more effective at convincing the other person that you can come to a satisfactory solution together. Thompson contends that by learning to respond using Verbal Judo, you can avoid harming other people, even when the situation gets tense.

(Shortform note: Responding instead of reacting sounds great, but it often doesn’t come naturally. That’s why law enforcement officers take “stress inoculation training,” which simulates stressful situations so officers can see how they naturally react and learn to respond instead, according to The Entrepreneur’s Solution author Mel Abraham. The name “stress inoculation training” is shared with a form of therapy that helps people with PTSD or anxiety prepare for stressful situations. Therapy exposes them to feelings of fear so they can respond more effectively when they feel afraid in everyday life. In much the same way, Abraham advises role-playing stressful situations to see how you naturally react. Then, you can learn to respond more productively.)

What Can Martial Arts Teach You About Communication?

Since a verbal confrontation can feel like an attack, martial arts like judo and karate offer a useful metaphor for different ways to handle the situation. Thompson argues that it’s most effective to respond to a confrontation like a practitioner of judo: by evading your opponent’s attack, using their momentum to take them off-balance, and gently moving them in the direction you’d like them to go. It might feel more natural to react like a practitioner of karate: by fighting back against your opponent, striking them, and forcing their cooperation. But only when you use a judo-like approach can you channel your opponent’s energy toward reaching a resolution.

(Shortform note: Thompson, who held black belts in judo and taekwondo, turns to karate as a metaphor for a forceful communication style. But practitioners say that karate is more than punching and kicking, and one of the fathers of modern karate emphasized that “You never attack first in karate.” A core principle of many martial arts is kuzushi, or unbalancing your opponent. As Thompson notes, this principle is easy to see at work in judo. But, it also guides practitioners of karate: Kuzushi involves taking someone off-balance physically and mentally by making them focus on regaining their equilibrium. In karate, striking is one way to take someone off-balance, and a well-timed strike serves the purpose of getting them to stop attacking you.)

Thompson writes that, when you use Verbal Judo, you can communicate with other people effectively to reach a resolution that benefits everyone while minimizing the effort you expend to reach that resolution. This method also gives you a less aggressive approach to conflict. That means you protect yourself from getting hurt and avoid bruising other people’s egos or damaging your relationship with them. When necessary, you can disagree with your friends, family, partner, or colleagues, but do so without hurting them. Thompson states that with Verbal Judo to guide you, you can strengthen your relationships as you find more effective ways to communicate with others.

(Shortform note: Thompson’s advice to find a solution that maximizes the benefits for everyone while minimizing the effort you expend echoes the first judo principle of Seiryoku zen’yō, or “Maximum efficiency, minimum effort.” In judo, you don’t have to have more strength than your opponent: You just have to make better use of your technique and timing to take them off-balance instead of resisting them directly. Judo practitioners say this leads to the second principle of judo: Jita-Kyoei, or “mutual benefit and welfare.” This means your interactions with other people should help you and them—whether you’re resolving a conflict at work or training in judo, where partners have to alternate taking falls so that each can practice their technique.)

What Are the Principles of Verbal Judo?

Verbal Judo incorporates three basic principles that help you to communicate more effectively in difficult situations: empathy, a mindset known as mushin, and impartiality. Thompson explains that each one serves a different purpose as you navigate a difficult conversation. By prioritizing empathy, you can turn down the temperature in a heated exchange. By practicing mushin, you can avoid reacting impulsively when you feel the heat. And by adopting an attitude of impartiality, you remind yourself that the temperature isn’t about you. We’ll discuss each of these principles in more detail.

Empathy

The most basic tool for practicing Verbal Judo is empathy: the ability to understand someone else’s perspective, even if you disagree with them or their interpretation of the situation. Thompson explains that empathizing with the other person, no matter how unreasonable you might think they’re being, enables you to take the tension out of the situation. That’s because practicing empathy helps you give people what they want: to be understood. Demonstrating that you’re trying to understand what the other person needs and listening to what they’re saying can go a long way toward getting them to dial back their language, even when they’re still feeling angry or upset.

According to Thompson, empathizing with another person doesn’t just make them feel understood—it also helps you see their perspective and understand what they need from you. When you show that you understand the problem and are working toward a solution, the other person will feel reassured that you recognize how they’re feeling. For example, imagine you have to tell your team that a project they’ve been working on has been put on the back burner. Your colleagues might get upset, since they’ve worked hard to finish it on time. To practice empathy, you might acknowledge their work and their disappointment. By validating their feelings, you reduce the tension in the room, even though everyone still feels disappointed.

Mushin

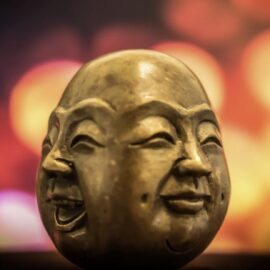

A second core skill in Verbal Judo is cultivating a mindset called mushin (wushin in Chinese), which practitioners of many Japanese and Chinese martial arts aim to achieve. Thompson explains mushin as a mental state where you remain calm even amid a chaotic situation, intentionally observe what’s happening around you, and stay in control of how you respond. He explains that staying calm enables you to stay centered, no matter how stressful the situation or how much the other person resists resolving the conflict.

Thompson notes that cultivating mushin also enables you to let go of any fear or anger that you might naturally, even justifiably, feel when someone is insulting or berating you. Mushin ties into another lesson of Verbal Judo: It’s better to deflect, rather than engage with, verbal abuse, particularly if you work in a public-facing role, like customer service. For example, you might draw on mushin when a customer yells at you because their delivery was late, the shipment was wrong, and on and on with more complaints. Even if you feel frustrated, you can focus on listening calmly. That way, instead of struggling to get a word in edgewise or obsessing over what you’ll say when they finally pause to take a breath, you can focus on engaging more thoughtfully with the conversation and resolving the problem.

(Shortform note: Thompson advises staying calm in the face of verbal abuse, but sometimes it’s not so simple. For example, many women find it scary or dangerous to turn down advances from men, who can view women as owing them attention and sometimes respond to rejection with abuse. In Men Explain Things to Me, Rebecca Solnit writes that society teaches men they have a right to control women: how they behave, when they talk, and even if they’re allowed to live. In the same vein, Margaret Atwood has noted that while men fear that women will laugh at them, women fear that men will kill them. And for some groups of women—women of color, trans women, and women who do sex work—refusing men’s advances is particularly likely to result in aggression and violence.)

Impartiality

A third principle of Verbal Judo is to adopt an attitude of what Thompson calls “disinterest” toward personal insults or attacks that might come your way. It’s one thing to stay calm when someone gets angry about something that doesn’t directly involve you—but it’s quite another to keep your cool when they insult you personally. Adopting an attitude of impartiality means that you don’t take it personally when someone says something hurtful to you, because people often say things they don’t mean in the heat of the moment.

(Shortform note: Like some of the other principles that Thompson incorporates into Verbal Judo, you can understand disinterest as a spiritual virtue as well as a tool to use in difficult conversations. Medieval theologian Meister Eckhart wrote about disinterest as the highest of virtues, one that can bring us closer to God as we learn to let go of the external world and our attachments to it. Scholar D.T. Suzuki compared the idea to the Buddhist principle of emptiness, which describes a way of perceiving the world directly, without getting caught up in our emotions and presumptions. By just watching your experiences, like anger or frustration, you can see them for what they are, no more and no less—a more enlightened mode of perception.)

Thompson explains that learning to avoid taking things personally keeps you and others from getting hurt. If you recognize that someone is only saying what they’re saying because they’re feeling frustrated, angry, or scared, then you’ll be less inclined to react to their words by saying things that might hurt them or even damage your relationship in the long run. By adopting an attitude of impartiality and not engaging with attacks or accusations, you can sidestep others’ most hurtful words and instead put the focus back on the issue at hand—like a judo practitioner who wants to dodge an attack rather than to mount an attack of their own.

For example, imagine that you’re at a neighborhood association meeting. If another member rudely interrupts you and criticizes your idea for renovating the community garden as “ridiculous” or “impractical,” you can maintain an attitude of impartiality. Instead of letting the harsh words derail you—and retaliating with some sharp words of your own—you can acknowledge his concerns and refocus the discussion. By staying impartial and deflecting the rude remarks, you keep the meeting productive and sidestep the personal attack.

(Shortform note: Other experts agree with Thompson that it’s best not to let angry words bother you. In The Four Agreements, don Miguel Ruiz writes that you should never take anything personally. Ruiz explains that when someone says something hurtful to you, that feedback says much more about them than it says about you. Everybody has their perspective and therefore has their truth, and Ruiz contends that their input is unimportant. By learning to not let other people’s words hurt you, you can become less afraid of being hurt. That, in turn, will make you more capable of being open and vulnerable with others.)

Exercise: Switch to a Verbal Judo State of Mind

Using martial arts as a metaphor for modes of communication, Thompson explains that it’s more helpful to focus on calmly redirecting the energy in a difficult conversation rather than to take an adversarial approach. But adopting that kind of stance takes some practice.

- Think about the last argument, confrontation, or difficult conversation you had. How would you describe how you handled it? Did you stay calm and collected, or did you try to counterattack?

- Consider how you could use the principles of Verbal Judo—empathy, mushin, and impartiality—to handle the situation differently next time. What do you think would change?

- Imagine what it might be like to make the same kind of adjustments to how you handle every difficult conversation. How might it make a difference at home, work, or other important areas of your life?