Silicon Valley’s brightest engineers optimize ads and build food delivery apps while America’s rivals race ahead in military AI—the technology that will determine 21st-century dominance. In their book The Technological Republic, Palantir executives Alexander C. Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska argue that the US tech industry is wasting its enormous talent on consumer products instead of on threats facing the nation.

Drawing on their experience building defense technology, the authors contend that the US must reunite Silicon Valley with the Pentagon, revive its sense of national purpose, and launch a “new Manhattan Project” to lead AI development. In this overview of The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West, we unpack Karp and Zamiska’s argument—examining what they contend the US has lost, how cultural shifts have severed the tech-government partnership, and what they say must change.

Table of Contents

Overview of The Technological Republic

While Silicon Valley’s brightest engineers build apps that make it easier to summon taxis and order burritos, the US’s rivals are racing ahead in AI, the technology that will determine who dominates in the 21st century. This is the warning of the 2025 book The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West by Alexander C. Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska. The authors argue that this misalignment of resources is threatening the US’s position in the world just as AI begins to replace nuclear weapons as the foundation of military deterrence. The solution, they write, calls for Silicon Valley to reunite with the defense establishment, for Americans to recover a sense of national purpose, and for the government to launch a “new Manhattan Project” to ensure American dominance in military AI.

Karp is the CEO and cofounder of Palantir Technologies, a data analytics company that has staked its business on government contracts rather than consumer products, selling software to intelligence agencies, militaries, and law enforcement—and making it a controversial outlier in Silicon Valley. Zamiska is Palantir’s head of corporate affairs and legal counsel. Karp holds a PhD in social theory from Germany’s Goethe University and identifies as politically progressive, though the book mounts a defense of American military power and a critique of the cultural forces—from 1960s counterculture to postmodern academia—that Karp and Zamiska believe have eroded the US’s sense of national purpose and left the tech elite morally unmoored.

In this overview of their book, we’ll break down Karp and Zamiska’s argument into three parts. We begin with their diagnosis of the problem: how the American tech industry severed its partnership with the defense and intelligence establishment and why the rise of military AI makes this abandonment dangerous. We’ll then examine their proposed solution—three core principles for rebuilding what they call a “technological republic”—and explore their practical recommendations, drawn largely from Palantir’s organizational culture and its battles against the military procurement process.

How Did the American Tech Industry Lose Its Way?

Karp and Zamiska argue that the American tech industry has abandoned its historic mission of serving national security and now wastes extraordinary talent on trivial consumer products, rather than addressing society’s most pressing challenges. Engineers spend their time optimizing advertising algorithms and building food delivery apps, and the companies they work for largely view the government as an obstacle rather than a collaborator. When engineers do encounter opportunities to work with military or intelligence agencies, they often protest, forcing companies to withdraw from defense work entirely.

The authors contend this shift has occurred because the tech industry’s current leadership consists largely of people they call “technological agnostics,” who build things simply because they can, not because they’re motivated by a larger vision of collective purpose. Karp and Zamiska argue that cancel culture has taught these executives to avoid expressing authentic beliefs or making value judgments for fear that others might disagree with them, which leaves them with no direction except what the market rewards. In this section, we’ll explain the historical partnership between technology and government, how cultural and intellectual shifts broke it, and why the rise of military AI makes this shift particularly dangerous.

The Historical Partnership Between Technology and National Defense

Karp and Zamiska explain that we have to look back to World War II to understand the direction and purpose that the tech industry has lost. They argue that engineers and scientists in this era felt a responsibility to support the state that made their work possible. They didn’t view their talent as belonging solely to themselves, but saw themselves as participants in a larger national project. They directed their skills toward challenges that the government identified as priorities, even when those challenges involved building weapons. Karp and Zamiska point to the development of nuclear weapons through the Manhattan Project as an example of this sense of national purpose.

The World War II era partnership between technology and defense continued into the Cold War era. Karp and Zamiska explain that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funded the computer networking research that would build the internet.

Silicon Valley as we know it today emerged from the work of defense contractors like Lockheed and Fairchild Camera, who built reconnaissance systems and military technologies for the government. But according to Karp and Zamiska, three cultural and intellectual changes that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s severed the partnership (and sense of shared purpose) that had united the people who were making science and engineering breakthroughs and the people who were tasked with protecting national security.

Counterculture Eroded Trust in the Government

The first cultural change to strike at the partnership between technology and defense was the rise of counterculture and the war in Vietnam, which created lasting skepticism toward government authority and military power. Karp and Zamiska explain that the pioneers of personal computing (like Lee Felsenstein, who founded the Homebrew Computer Club) distrusted governments and corporations, and they saw their work as liberation from institutional control. Apple cofounder Steve Jobs embodied this shift: Apple’s famous 1984 advertisement showed personal computers liberating individuals from an Orwellian dystopia of governmental control, an image at odds with the earlier idea that government could be a partner worth serving.

Academic Movements Undercut Collective Identity

Second, academic deconstruction dismantled shared Western identity. Karp and Zamiska write that beginning in the 1960s, universities eliminated the Western Civilization courses that gave students a common intellectual foundation. This trend accelerated after cultural critics—such as Edward Said in his 1978 book Orientalism—argued that the historical narratives that academics teach constitute exercises of power rather than objective truth.

Karp and Zamiska contend these cultural critiques created a generation that felt skeptical of collective American identity, but had nothing substantial to replace it. Previously, the authors suggest, Americans shared a narrative of Western civilization as democratic, rational, and committed to liberty. After deconstruction, belonging to America meant little more than respecting others’ rights and participating in free markets, which gave no meaningful direction.

Consumerism Replaced What Was Lost

Third, market forces filled the vacuum left by the disappearance of collective purpose. Karp and Zamiska argue that when the US’s shared national identity weakened and trust in government eroded, the consumer market became the default mechanism for determining what technologies should be built. This redirected development toward whatever consumers would pay for. By the 2010s, the industry’s rallying cry had become simply “to build,” with few people stopping to ask what really needed to be built or why. Following the demands of the consumer market, engineers channeled their talents into apps that make people feel wealthier by summoning transportation, ordering food, and booking accommodations with a few taps.

Why Does This Matter Now?

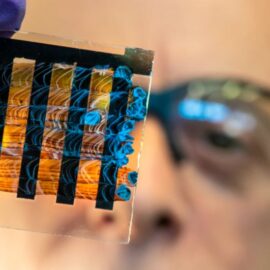

The abandonment of national purpose would be concerning in any era, but Karp and Zamiska argue it’s particularly dangerous as increases in computational power and advances in deep learning make AI much more capable. The large language models (LLMs) that have become ubiquitous may be approaching human-level reasoning. Specialized AI systems will soon be integrated into autonomous weapons, drone swarms, and targeting systems that will be able to make battlefield decisions faster than humans can process information. AI will determine military outcomes in the 21st century the same way nuclear weapons did in the 20th, and this focus is existentially urgent because adversaries are already developing these capabilities.

The authors note that unlike nuclear weapons, which required massive industrial infrastructure and rare materials, AI development depends primarily on software expertise and computing power—two areas where the US should have decisive advantages. However, Karp and Zamiska contend that the technology will be developed with or without American companies’ involvement: Because they have the unity of purpose that the US lacks, China and other authoritarian rivals are already racing ahead in facial recognition technology and military drone swarms. When talented American engineers refuse to work on military AI, they don’t prevent such weapons from existing—they simply ensure that America’s adversaries will deploy them first.

What Needs to Change?

Karp and Zamiska argue that the US must restore what they call a “technological republic,” a tradition they trace to the nation’s founding, when leaders like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were themselves scientists and engineers. They envision an American society where the tech industry reunites with government to serve national purposes, like defense and intelligence, where engineers and business leaders have collective goals, and where the pursuit of overwhelming AI superiority becomes a shared priority.

In this section, we’ll explain the three conditions the authors believe are necessary to remake the US as a technological republic: the tech industry reuniting with the defense and intelligence establishment, Americans recovering collective belief in national purpose and Western values, and the US government pursuing AI dominance through massive investment.

The Tech Industry Must Reunite With Government

First, Karp and Zamiska advocate for the tech industry to reunite with the government. They believe tech companies must prioritize working on defense, intelligence, and other “public goods.” One reason to rebuild this partnership is that markets don’t naturally prioritize what society needs most urgently. So if companies continue building whatever generates the highest returns, they won’t tackle the hard problems in national security and law enforcement that the government is working on. The authors also argue that the industry has a responsibility to support the state that enabled its success, since the American system of universities, capital markets, legal protections, and infrastructure made Silicon Valley possible.

Karp and Zamiska write that the tech industry should work with the government because only the government can coordinate technological development at the scale required to maintain military superiority and AI dominance. They argue tech companies should view the government as a collaborator rather than an obstacle, and that engineers should see working on national security challenges as honorable rather than morally suspect. The industry should also accept that some of its most talented people should be working on problems the government identifies as priorities—autonomous weapons systems, surveillance technologies, battlefield AI—even if those applications make some people uncomfortable.

America Must Recover Its Belief in National Purpose

Second, Karp and Zamiska argue the US must reject cultural relativism—the idea that no culture or set of values is better than another—and recover its conviction about national identity and the superiority of western civilization. They see this shift as necessary because the intellectual movements that dismantled university courses on western civilization—and taught that western narratives of democracy and progress were just exercises of power—trained students to be suspicious of claims about values or purpose. This created a reluctance to commit to any belief that might offend someone or course of action that might limit someone else’s choices; anyone taking a strong position now risks being accused of cultural imperialism or insensitivity.

The authors argue this intellectual stance has become destructive because it prevents societies from articulating any shared purpose or defending any particular way of life. If no values are better than others, then there’s no basis for saying democracy is preferable to authoritarianism, or that individual rights matter more than state control. People educated in this framework have no way to explain why the tech industry should work on collective challenges rather than just pursuing profit. Karp and Zamiska contend that this leaves much of Silicon Valley knowing that they oppose certain things (like building technology for the military), but without the ability to articulate what they support or believe America should stand for.

Karp and Zamiska argue it’s crucial that the US recovers its collective belief, not just personal conviction, because democracy requires more than just individual rights and market economics to function. It needs cultural coherence, which consists of shared stories, rituals, and values. People need a purpose to motivate them to tackle difficult challenges—something more than wealth, and more like the national goals that the US’s authoritarian rivals use to mobilize societies. Karp and Zamiska insist the US must rebuild a shared culture and recover its belief in Western values—and they emphasize democracy, individual rights, and technological progress as core to Western identity.

The US Must Pursue AI Dominance

Third, Karp and Zamiska call for a “new Manhattan Project” to develop AI systems for defense. They look to the Cold War to explain why we should see this as an urgent priority. During the Cold War, peace rested on mutually assured destruction: No nation would start a war that would end in annihilation for both sides, making parity in nuclear arms capability sufficient for preventing all-out war. But in AI-powered warfare, they argue, the decisive advantage will belong to whoever develops the most sophisticated systems first. Achieving overwhelming superiority could secure American power for generations.

Karp and Zamiska argue the tech industry must commit its capabilities to making AI development a national priority. They outline an ambitious vision for a new Manhattan Project: government funding at unprecedented scale for AI research with military applications; collaboration between Silicon Valley and the Department of Defense, intelligence agencies, and the military; and a focus on developing autonomous weapons, targeting systems, drone swarms, and other tech that can make decisions faster than humans.

How Can We Build a Technological Republic?

Karp and Zamiska offer their experience at Palantir as a model for how to build the technological republic they envision. Their recommendations, which we’ll explore in this section, are intended for several different audiences: private organizations, government agencies, and public institutions. They offer a vision of how the US can put outcomes above bureaucracy, make innovation accessible to the government, and ensure that the people making decisions have stakes in the technological republic they’re building.

Distribute Authority to Those With Direct Information

First, Karp and Zamiska argue that innovative organizations should give decision-making power to the people closest to actual problems, rather than forcing everything to go through management hierarchies. This principle applies to any organization facing complex, rapidly changing challenges, whether they’re tech companies, government agencies, or corporations working in more traditional industries. The authors believe this approach played an important role in Silicon Valley’s early successes, but as companies grew, many of them lost this culture. Government agencies, in particular, desperately need to learn it.

Palantir applies this through what the authors call “shadow hierarchies,” where the formal trappings of hierarchy are absent: no org charts determining who has authority, no corner offices or reserved parking signaling status. Authority still exists, but it isn’t formalized in job titles or reporting structures. This means talented people can claim authority by simply doing the work, rather than first asking permission from clearly-defined bosses. While Karp and Zamiska admit this creates some confusion about who’s in charge of what, it enables people to step forward and solve problems. This approach relies on having a founder or clear ultimate authority who can serve as final arbiter when needed.

Palantir also encourages what Karp and Zamiska call “constructive disobedience.” This means employees can challenge how leadership wants to implement strategy (though not the strategy itself). Like musicians in an orchestra who have expertise the conductor lacks, employees absorb the overall direction, but then reshape the business’s tactical approaches to get better results. The authors explain that this contrasts with the emphasis that many traditional corporations place on rewarding compliance, which undermines innovation because people stop thinking critically about whether they’re solving problems in the right ways.

Require Government to Buy Commercial Technology When It Exists

Karp and Zamiska’s second recommendation for how to build a technological republic targets a specific barrier preventing tech companies from working with the government: Federal agencies default to building custom systems rather than buying proven commercial products. The authors argue that instead, government agencies should be required to evaluate whether commercial solutions already exist before spending years and billions of dollars developing their own.

The current procurement system (and its extensive red tape) emerged from good intentions: In the 1980s, reports that the Navy paid $435 for hammers sparked outrage about wasteful military spending. Congress responded with regulations to prevent the government from overpaying so egregiously. However, the procurement rules became so burdensome that they soon prevented even basic purchases.

For example, during the Gulf War, the Air Force couldn’t buy two-way radios from Motorola because regulations required cost-tracking systems the company didn’t have. A 1994 law, the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act (FASA), tried to fix this by requiring agencies to buy commercially available products whenever possible, but for years, agencies largely ignored this rule, continuing to favor traditional defense contractors who build custom systems to their specific requirements.

Karp and Zamiska claim a breakthrough happened when Palantir sued the Army in 2016 for failing to even consider its commercial software for a battlefield intelligence contract. A federal judge ruled the Army had to evaluate whether commercial options existed. Three years later, the Army awarded Palantir the contract—the first time a Silicon Valley software company beat traditional contractors to lead a major defense program. The authors argue that this shows what must change: Government agencies need to actually enforce the 1994 law, and when a proven commercial solution exists, the government should buy it rather than spending years building an inferior version from scratch.

Give Employees Ownership in What They’re Building

Karp and Zamiska’s third recommendation for building a technological republic is that organizations should give employees equity stakes so their personal wealth depends on the company’s long-term success, not just on steady paychecks that arrive regardless of results. Beginning in the 1960s, Silicon Valley pioneered giving equity to all sorts of employees, not just executives—even administrative staff and junior engineers got ownership stakes. This created a culture where everyone participated materially in the company’s success. The authors argue this alignment of interests drove much of Silicon Valley’s growth: When people own part of what they’re building, they think like owners focused on long-term value, rather than like employees just trying to keep their jobs.

Pay Government Officials Competitive Salaries

The fourth recommendation the authors make is that the government should pay senior officials salaries competitive with what talented people earn in the private sector. Karp and Zamiska point to the chairman of the Federal Reserve, who earns roughly $190,000 annually—less than entry-level investment bankers—despite managing decisions that affect trillions of dollars and hundreds of millions of people. This creates two bad outcomes: Either only wealthy people can afford to work in public service, or officials have to cash in later through lucrative corporate board seats, speaking fees, and consulting contracts after leaving government.

Singapore offers an alternative model. Under Lee Kuan Yew, the country tied ministers’ salaries to comparable private sector positions, with senior officials earning over $1 million annually. The authors argue this attracts top talent into government and reduces corruption by making official compensation itself attractive enough that people don’t need side deals or post-government paydays. The logic is similar to giving employees equity: When decision-makers’ personal financial success depends on doing their jobs well—whether through company ownership or competitive government salaries—their interests align with long-term institutional success rather than with personal survival or future enrichment opportunities.