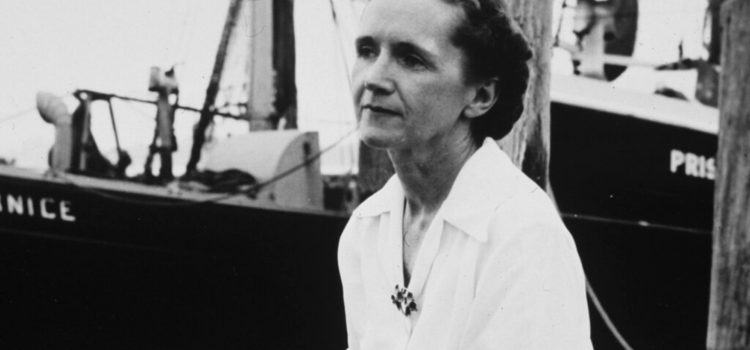

Why did biologist Rachel Carson criticize pesticides? How effective are pesticides for pest control?

According to Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, pesticides aren’t necessary to protect food in countries like the United States. She also argues that they threaten the nature of the ecosystem and ultimately strengthen pests.

Continue reading to learn more about Carson’s findings on pesticide usage.

Are Pesticides Effective?

Throughout Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, pesticides are questioned for their efficiency compared to other, less environmentally devastating methods of pest control. She also questions the need for the massive chemical campaigns of the 1950s and early ’60s, in which millions of acres of American land were sprayed and entire communities of animals wiped out. Many of these campaigns failed to meaningfully reduce the population of the target species, and some of those species built up resistances to pesticides over time, requiring the application of more dangerous chemicals in greater amounts every year. In Carson’s view, these repeated and ineffective campaigns threaten to wipe out entire species and waste millions of US taxpayer dollars.

(Shortform note: Though the kind of aerial spraying campaign Carson describes has been banned in the European Union, the practice continues in places like the US, Japan, and Costa Rica. Most recently, in 2015, Colombia banned aerial spraying of glyphosate—used to target coca fields and undermine the cocaine trade—over concerns that the chemical was carcinogenic.)

Carson cites three major arguments against pesticides: They aren’t needed to protect the food supply of countries like the US, they disrupt the balance of various populations in an ecosystem, and they may ultimately make pests stronger by allowing them to build up resistance to chemicals through repeated sprayings.

Pesticides Are Unnecessary

While pesticides supposedly protect crops and thus the country’s food supply, Carson points out that the US was actually dealing with an overproduction problem in the 1950s-’60s. Far from needing to be concerned about food shortages, Americans in 1962 were paying millions of dollars in taxes to store excess food, most of which would go bad before reaching consumers.

(Shortform note: Overproduction and food waste remains a persistent issue in the US today, with an estimated 30-40% of all produce being thrown out rather than consumed, even as many Americans living in poverty are malnourished. This problem worsened during the 2020 Covid-19 outbreak as many restaurants and schools closed and farmers were forced to dump products that had gone bad. Beyond the economic waste, overproduction contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and overwhelms landfills.)

Carson argues that in addition to the arbitrary nature in which plants are labeled weeds, many of the insects that were the subject of extermination campaigns, such as the invasive Japanese beetle, pose only a limited danger to native species. Ultimately, Carson suggests the need for pesticides may be deliberately exaggerated by chemical companies in order to sell products.

(Shortform note: Japanese beetles are harmless to humans, and the damage they do to plants is mostly aesthetic; they feed on the grass of golf courses and suburban lawns and many flowering plants. Other environmentalists since Carson have accused the chemical pesticide industry of exaggerating its importance in protecting the global food supply, arguing that the problem is not a food shortage so much as distribution and economic inequality. Despite this, the industry still makes billions of dollars each year.)

Pesticides Disrupt the Balance of an Ecosystem

While pesticides are deadly, some species are naturally resistant to them. These species’ survival, while their natural predators die en masse, may lead to overpopulation, which can devastate an environment worse than the spraying itself. For example, the spraying of Douglas firs to kill spruce budworms led to those firs becoming infested by spider mites instead. The same occurred in Louisiana sugarcane fields, where fire ants were killed off to protect people from their sting and the population of sugarcane borers subsequently exploded. Finally, spraying campaigns might even kill off the natural predators of the target population, allowing the pest to return in greater numbers the next year.

(Shortform note: Additional evidence for Carson’s claim that pesticides don’t solve the problem can be seen in the fact that both Douglas firs and sugarcane fields are still threatened by pest infestations, despite decades of spraying. These threats include both the targets of previous spraying campaigns and the naturally resistant species Carson discusses. Interestingly, fire ants are now sometimes used as a biological control against sugarcane borers, encouraged to remain in the environment rather than being targeted by pesticides.)

Pesticides Lead to Pests Building Up Resistance

Beyond the fact that pesticide campaigns sometimes fail to kill the targets in the first place, Carson argues that there’s evidence that insecticides are becoming less effective over time as insects build up natural resistance and even immunity to the chemicals used. Because insects generally live for a much shorter time than humans, several generations can live and die in the space of months or even weeks. While some are killed off by pesticides, those that survive pass their more resistant genes on to their children. This might mean possessing an enzyme that allows them to detoxify DDT inside their body or a tendency toward behavioral patterns such as nesting outside rather than on walls sprayed with pesticides.

(Shortform note: Carson is describing the process of natural selection, in which members of a species that possess traits conducive to survival tend to outlive their peers and pass those traits on to their offspring, resulting in changes to the species as a whole over time. For example, Charles Darwin famously theorized that various species of Galápagos finches had developed different beak shapes depending on which best suited their diet. Since Silent Spring was published, the kinds of biological and behavioral changes Carson describes have been observed in mosquitoes worldwide.)

Carson argues that the result of pesticide campaigns, then, has not been to reduce target populations, but to make those target populations stronger against human intervention. Carson notes that this is particularly troubling for campaigns against the spread of diseases like malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and typhus through mosquitoes, flies, and lice. The response of the chemical industry has been to use deadlier poisons in greater amounts, which will further devastate the environment long before it has any meaningful effect on the pests. Most species reproduce on a much slower timescale than insects, and Carson estimates that it would take hundreds if not thousands of years for humans to develop a natural resistance to pesticides.

(Shortform note: Some of Carson’s critics argued that by campaigning against pesticides, she was dooming the world to mass deaths from diseases spread by insects, particularly malaria. However, not only did Carson support the use of pesticides against malaria but modern evidence also suggests that her predictions were correct—mosquitoes are increasingly resistant to any form of chemical treatment. Some scientists are pushing for biological controls, such as infecting mosquitoes with a bacteria that could inhibit their ability to spread malaria, to be used instead.)