Have you ever wondered why your best intentions crumble? The answer isn’t a lack of willpower—it’s a misunderstanding of how your brain actually works. According to psychologist Wendy Wood’s research, roughly 43% of your daily actions are automatic habits. This means that no amount of willpower can directly override these deeply embedded behaviors.

Wood’s insights in her book Good Habits, Bad Habits reveal that successful habit change requires working with your brain’s natural systems rather than fighting against them. By understanding the three key elements that create habits—context cues, repetition, and rewards—you can redesign your environment and behaviors to make lasting change effortless. Keep reading for a full overview of Wood’s book.

Good Habits, Bad Habits Book Overview

Have you ever tried to change a habit, only to find yourself reverting to your old ways no matter how hard you try? Do you believe that your inability to change is due to a lack of willpower or self-control? According to psychologist Wendy Wood, this isn’t the case.

In the book Good Habits, Bad Habits (2019), Wood argues that you’re fighting a losing battle when you rely on willpower alone to change habits—because the harder you try to overcome unwanted habits, the stronger those habits become. She suggests that understanding how habits form can help you easily and effectively change your unwanted habits or introduce new ones without having to rely on constant willpower.

Wendy Wood is the Provost Professor of Psychology and Business at the University of Southern California. She’s published over 100 scientific articles on habits, attitudes, and behavior change, and her research has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and on NPR.

This guide walks you through Wood’s ideas in three parts:

- Part 1 explains why habits form and why they’re immune to conscious intervention.

- Part 2 outlines the conditions required for behaviors to become habits.

- Part 3 provides methods to change your unwanted habits or form entirely new ones.

We’ll also expand on her insights with research and actionable methods from other behavioral scientists and psychologists.

Part 1: You Don’t Consciously Control Your Habits

While you may assume you consciously choose your behaviors, Wood argues that 43% of your daily actions are automatic habits. It’s difficult to be aware of or control these habits because they operate on a system that’s independent from your conscious mind.

Wood explains that your brain relies on two distinct operating systems to guide your behaviors—conscious and habitual:

- Your conscious system requires active attention and effort to operate. It enables you to plan, make decisions, and solve complex problems. However, it has a limited capacity and is easily depleted.

- Your habitual system doesn’t require your attention or input to operate. It enables you to perform routine tasks without having to consciously think about them.

According to Wood, your brain relies heavily on your habitual system because, without it, you’d be too overwhelmed to function. To clarify her point, we’ll first explore how your habitual system saves mental energy, helping you engage in routine behaviors without conscious thought. Then, to help you understand why willpower alone isn’t sufficient for changing habits, we’ll explain how your habitual system resists change by protecting your habits from conscious intervention.

Your Habitual System Saves Mental Energy

Your habitual system saves mental energy by taking control of the things you do most often so you can perform them without actively thinking about them. Wood explains that each time you learn or do something new, you need to focus your attention, make a conscious effort to process information, and then make decisions based on what you’ve learned. This takes up a lot of mental energy, restricting your ability to think about or achieve anything else. For example, recall the first time you signed your name. You had to concentrate fully on the task, work out how to do it, and figure out your preferences: What’s my name? How do I spell it? Do I want to include all my initials or just the first? What style do I like?

Without your habitual system, you would have to relearn every single thing you do every time you do it, processing information and making decisions every step of the way. This would drain your cognitive resources, leaving you in a constant state of mental exhaustion. However, your habitual system preserves your mental energy—it allows you to perform routine tasks automatically, freeing your conscious mind to think about other things, like creative projects or complex problems. For example, your habitual system lets you sign your name and plan how you’ll respond to a thorny work email at the same time.

Your Habitual System Ensures Consistent Behavior

By taking control of your routine actions, your habitual system ensures that you can perform actions consistently without conscious intervention. For example, you automatically do things like brushing your teeth or showering the same way every time without having to think about how you’ll do them.

Your habitual system can ensure this consistency because, once it takes control of a behavior, it permanently stores that behavior in the part of your memory known as procedural memory. Unlike the adaptable part of your memory that stores facts, experiences, and conscious knowledge, procedural memory is designed to preserve learned behaviors and routines so that you never have to waste energy relearning them. This explains why, for example, you can ride a bicycle even after years of not practicing.

Feelings, Intentions, and Knowledge Don’t Influence Your Habitual System

While your habitual system saves you mental energy, it has a significant drawback: Once it takes control of a habit, it drives you to engage in that habit regardless of your conscious intentions. Wood explains that factors like your mood, energy level, and acquired knowledge influence your conscious system. There, they impact your moment-to-moment thoughts and intentions (like what habits you want to continue). But since your conscious and habitual systems are separate, these factors can’t change the routine behaviors stored in your procedural memory (part of the habitual system). So, your brain compels you to keep acting out of habit, even if you consciously decide to change that habit.

For example, say you habitually drink coffee first thing in the morning. If you wake up feeling energetic without it, or you learn about the negative effects of caffeine, you might decide to stop drinking coffee every morning. But this conscious intention won’t touch your procedural memory. Your habitual system will drive you to automatically reach for a cup every morning, regardless of whether or not you want to drink coffee.

How Exerting Willpower Backfires

Wood explains that it’s possible to consciously redirect a habit once in a while—for example, you might successfully abstain from coffee one morning out of five. However, since conscious intentions can’t change the routines your habitual system has permanently stored, you’d need to consciously fight your habitual system every time it drives your habit. And each attempt at changing that habit would require you to exert a great deal of conscious effort. For example, you’d need to consciously push back against your coffee-drinking habit every morning.

Wood explains that exerting willpower in this way often backfires, causing you to quickly revert to the habits you intend to change. This is because while your feelings, intentions, and knowledge don’t influence your habitual system, your level of mental energy does. When you’re running low on mental energy—due to cognitive strain, stress, or tiredness—your brain shifts even more control to your habitual system so it can protect and replenish your energy reserves.

Put simply, the more you try to consciously control your habits, the more you deplete your mental energy—and your ability to consciously redirect your habitual behaviors. You end up in a losing battle where your efforts to change strengthen the system that drives the behaviors you want to avoid.

Part 2: How Behaviors Become Habits

Although willpower alone is insufficient for changing habitual behaviors in the long term, and your habitual system is built to be resistant to change, Wood suggests that it is possible to control habits. To achieve this, you first need to understand the specific conditions required for behaviors to become habits. She explains that to solidify as automatic actions in your habitual system, habits require three interdependent elements: context cues, repetition, and rewards. Let’s explore each of these.

Element #1: Context Cues

Context cues are environmental triggers that prompt your habitual system to execute a specific habit. These cues encompass everything surrounding you when you perform a behavior, like the physical location, an object, the time of day, people present, or preceding actions. Wood explains that when you repeatedly perform a behavior within a specific context, your habitual system associates that context with that behavior—turning it into a habit. For example, if you regularly reach for the TV remote when you sit on the sofa, your habitual system associates your sofa (the context cue) with reaching for the remote (the behavior). As a result, you develop a habit of reaching for the remote as soon as you sit on the sofa.

Once your habitual system cements a context-behavior association, it drives you to automatically engage in the behavior every time you’re in that context. This process happens so fast that you often don’t have a chance to consciously decide what you want to do. For example, when you sit on the sofa, your habitual system pushes you to reach for the remote, even when you don’t feel like watching TV.

Consistent Patterns Create Context-Behavior Associations

Wood adds that your habitual system struggles to form context-behavior associations when your behavioral patterns are unpredictable or inconsistent. This inconsistency occurs when you:

- Perform the same behavior in different contexts: Sometimes, you also reach for the remote when talking on the phone, playing with your kids, or eating dinner.

- Perform different behaviors in the same context: Sometimes you pick up a book or a sewing project when you sit on the sofa.

This is because your habitual system relies on behavioral patterns to form your habits: When you regularly perform a specific behavior within a specific context, it sees a clear pattern and creates a context-behavior association, turning that behavior into a habit. However, when you keep changing your behaviors or their contexts, your habitual system fails to detect a pattern and doesn’t form the context-behavior association required to turn that behavior into a habit.

This explains why habits are often situation-dependent. For example, say you regularly reach for the remote when sitting on your sofa, but don’t do so when sitting on a sofa in someone else’s home. In this case, your habitual system will only push you to engage in this habit when you’re at home.

Element #2: Repetition

As we’ve discussed, your habitual system relies on behavioral patterns to form context-behavior associations. This is why the second element of habit formation—repetition—is so important: The more often you engage in the same behavior in the same context, the easier it is for your habitual system to identify a pattern and form a context-behavior association. However, Wood explains that even after your habitual system forms a context-behavior association, it relies on repetition to turn that association into an automatic habit.

This is due to the way neural pathways inform your behaviors: When your habitual system first forms an association, the neural pathway connecting the context cue to the behavior is weak and underdeveloped—meaning it’s not yet the default response for that cue. As a result, you still need to apply conscious effort to perform the behavior in that context. For example, before TV-watching became a habit, you likely considered alternative actions when you sat on the sofa before deciding to pick up the remote.

However, repeating the same behavior in the same context strengthens this neural pathway, solidifying the connection between the cue and behavior until it becomes your default response. This lets your habitual system instantly respond to the cue without conscious involvement: It activates the behavior before you have time to consider other options. At this point, the behavior has become an automatic habit.

How Long Does It Take to Form an Automatic Habit?

According to Wood, there’s no set timeline for when context-behavior associations become automatic. This process depends on the complexity of the behavior, how consistently you do it in response to the cue, and your learning speed.

Element #3: Rewards

The third element of habit formation—rewards—helps your habitual system identify what context-behavior associations are worth reinforcing. Wood explains that enjoying a positive outcome for performing a behavior in a specific context releases dopamine (a pleasurable neurochemical) into your bloodstream. This dopamine release makes you feel good, teaching your habitual system to strengthen that context-behavior association.

According to Wood, rewards must be immediate, occurring within seconds or minutes of performing the behavior. This is because your habitual system learns from immediate consequences rather than long-term ones; it can’t identify a behavior as rewarding unless you enjoy a pleasurable dopamine release right away. She adds that you’re more likely to experience an immediate release of dopamine when you find the behavior itself enjoyable. For example, when you sit on the sofa and reach for the remote, you experience the immediate pleasure of relaxation.

Additionally, Wood suggests that variable rewards strengthen context-behavior associations. When rewards for performing a behavior are unpredictable—sometimes they’re big, but at other times less so—your habitual system never knows what to expect. This uncertainty about what reward you’ll receive keeps your habitual system in a state of anticipation. Each instance of engaging in the behavior could potentially offer a satisfying reward.

For example, if in addition to your regular shows you sometimes find movies you’ve been eager to watch, your habitual system will be in a greater state of anticipation each time you sit on the sofa. The possibility of watching something new creates more anticipation than always watching the same shows.

Wood explains that the more your habitual system anticipates a reward, the more dopamine gets released into your bloodstream in response to the context cue. This occurs while you anticipate it, before you perform the behavior. This anticipatory dopamine release teaches your habitual system to strengthen that context-behavior association more effectively than predictable rewards would.

Established Habits Continue Without Ongoing Rewards

Wood explains that the combination of repetition and rewards is important early on because it trains your habitual system to strengthen a context-behavior association. As we’ve discussed, this process solidifies the neural pathway connecting the context cue to the behavior, turning that behavior into the default, automatic response for that cue. Once a habit is solidified, you’ll engage in the behavior regardless of whether you receive a reward. This explains why you engage in habits that no longer appeal to or benefit you—for example, you sit on the sofa and reach for the remote even when you know there’s nothing worth watching on TV.

Part 3: How to Change Your Habits

We’ve just explained the three elements that fuel habits: context cues, repetition, and rewards. Now, we’ll explore how you can apply that information to change unwanted habits or create entirely new ones.

Change Unwanted Habits

Since established habits are permanently stored in your habitual system, you can’t simply delete the ones you no longer want. However, that doesn’t mean you’re stuck with them.

Wood suggests that you can break free from an unwanted habit by manipulating its context cue and replacing the associated behavior with a more productive one. This process doesn’t involve manipulating rewards since, as previously explained, established habits operate independently of rewards—removing the reward you receive for a habit won’t weaken its context-behavior association.

Wood offers three methods that, when used together, can help you redesign your unwanted habits: Remove context cues, make it inconvenient to engage in your default behavior, and replace your default behavior. Let’s explore each.

Method #1: Remove Context Cues

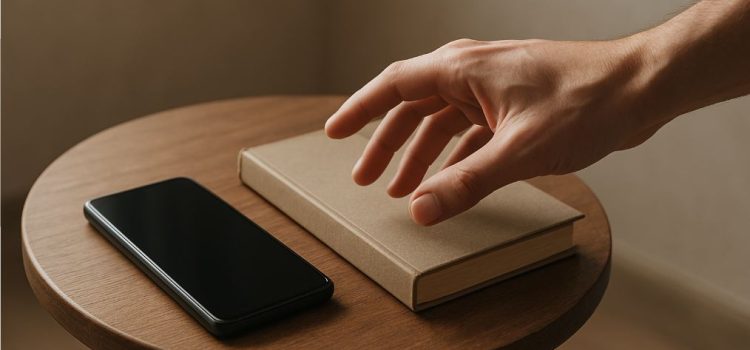

Since habits activate in response to specific cues in your environment, removing context cues for the habits you want to change can disrupt them. As Wood explains, without those cues, there’s nothing in your environment to trigger your habits. For example, you might move your sofa out of the TV room or, instead of keeping your remote next to your sofa, put it in the TV cabinet so it’s out of sight.

Method #2: Make It Inconvenient to Engage in Your Default Behavior

As it stands, you engage in your habits because they’re easy and don’t require any conscious effort—for example, keeping your remote next to the sofa allows you to reach for it without having to think about it. Wood says that making an unwanted habit inconvenient prevents you from automatically engaging in it when you see the cue. Instead, it forces you to make a conscious effort, which gives you a chance to redirect your behavior.

For example, let’s say you put the remote on a very high shelf and turn the TV to face the wall. After sitting on the sofa, you’d need to decide whether it’s worth making the effort to watch TV. Since this would involve finding a chair to stand on to reach the remote and fiddling with the TV to get it into the right position, you might decide that it’s not worth the effort.

Method #3: Replace Your Default Behavior

While removing context cues and making behaviors inconvenient are effective at disrupting unwanted habits, these methods alone won’t prevent your habitual system from driving you to engage in those habits when:

- You encounter context cues by chance—for example, if your partner leaves the remote on the coffee table.

- Circumstances prevent you from maintaining the inconveniences—for example, if your partner bans you from turning the TV to face the wall.

Therefore, Wood says you need to train your habitual system to associate the context cue for your unwanted habit with a behavior you want to engage in. To achieve this, consciously engage in your chosen behavior when you encounter the context cue. Repeat this new context-behavior pairing until your habitual system forms a strong association and turns it into a new automatic habit. For example, if you want to replace reaching for the remote with reading a book when you sit on the sofa, you need to consciously choose to read each time. With enough repetition, your habitual system will associate sitting on the sofa with reading, regardless of whether or not the remote’s within reach.

Form a New Habit

Unlike changing an unwanted habit, where you’re working against an existing context-behavior association, forming a new habit involves creating a context-behavior association from scratch. Wood offers four methods that, when practiced together, will enable your habitual system to turn your desired behavior into an automatic habit: Build on an existing habit, establish clear and consistent context cues, make it easy to engage in your desired behavior, and reward yourself.

Let’s explore how to apply these methods to form the new habit of taking vitamins every morning.

Method #1: Build on an Established Habit

Wood suggests that one of the most effective ways to form a new habit is to link it to an existing habit. This lets you leverage established context-behavior associations rather than creating entirely new ones. In other words, you can use an existing habit to trigger your desired habit. For example, if you already have a habit of drinking coffee every morning, you could place your vitamins next to your coffee machine and take them immediately after pouring your first cup. With enough repetition, your habitual system will associate that first cup with taking vitamins, eventually making vitamin-taking part of your habitual morning routine.

Method #2: Establish Consistent Context Cues

Since your habitual system relies on consistent patterns to form context-behavior associations, you’ll need to establish obvious context cues and a predictable routine to help your habitual system identify the new pattern and form a strong context-behavior association for it. This means performing your new behavior in the same context every time, such as at the same time or in the same location. For example, take your vitamins every morning after pouring your first cup of coffee while standing at your kitchen counter.

Method #3: Make It Easy to Engage in Your Desired Behavior

The less conscious effort a behavior requires—meaning the less you need to think about if you want to do it or how you’ll do it—the easier it is for your habitual system to make it automatic. Therefore, Wood suggests making your desired behavior as easy as possible. This involves identifying and removing any factors that might require you to make a conscious effort. For example, taking multiple vitamins requires you to open different bottles and take out vitamins one by one. You might minimize the effort required by pre-sorting your daily vitamins into a weekly pill organizer that you keep next to your coffee machine.

Method #4: Reward Yourself

As previously explained, rewards effectively strengthen context-behavior associations when they’re immediate, tied directly to performing the behavior, and unpredictable. Therefore, Wood suggests that you find a variety of ways to make your desired behavior feel more rewarding. For example, you might make the act of taking vitamins unpredictably enjoyable by mixing your favorite flavors, introducing gummy or effervescent vitamins into your mix, or sometimes taking them with sparkling water instead of regular water.

Exercise: Change an Unwanted Habit

Wood suggests that you can change unwanted habits by removing context cues, making it inconvenient to engage in your default behavior, and replacing your default behavior. In this exercise, we’ll explore how you can apply these methods to redesign one of your habits.

- Think of one habit you’d like to change and identify the specific context cue that triggers it. (For example, you might have a habit of eating chips every time you open the pantry door, with “seeing the bag of chips” being the context cue.)

- Consider how you can remove the context cue for this habit and write down at least one possibility. (For example, you might remove chips from your pantry or move them to a high shelf where they’re out of sight.)

- Think about how you can make it inconvenient to engage in the behavior that defines this habit and write down at least one option. (For example, you might store the chips in a locked container and keep the key in the basement.)

- Consider how you’d prefer to behave when you encounter the context cue and how you might make it easy to engage in this behavior. Write down at least one idea. (For example, if you’d prefer to eat nuts and dried fruits, you could keep them in a clear container and place them at eye level so you can see them every time you open the pantry door.)