Every US president leaves their mark on history—some as heroes, others as cautionary tales. Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard’s Confronting the Presidents: No Spin Assessments From Washington to Biden examines the personal lives and political legacies of the American presidents. The book reveals how the decisions, relationships, and character traits of these leaders shaped the country we know today.

Read more to explore how various presidents navigated the pressures of the highest office and what their stories teach us about America as a nation.

Overview of Confronting the Presidents: No Spin Assessments From Washington to Biden

Some US presidents are known as great heroes, some are remembered for their failures, and others are mostly forgotten. Nevertheless, all of them made their mark on American history. In Confronting the Presidents: No Spin Assessments From Washington to Biden, Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard look at the personal and political lives of every American president, from their meaningful relationships to the political crises and decisions that shaped their time in office. By doing so, O’Reilly and Dugard hope to help their readers understand America’s past and present on a deeper level.

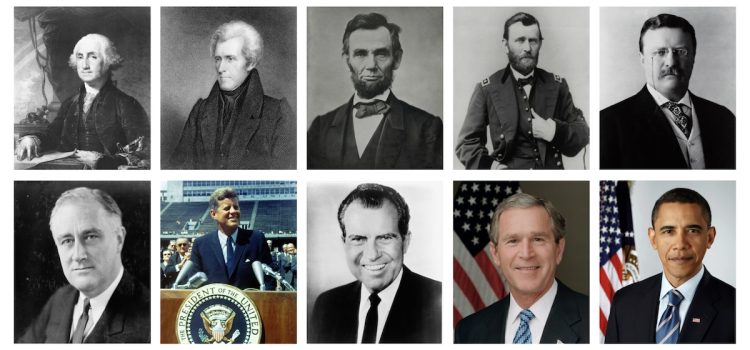

While Confronting the Presidents covers every president from Washington to Obama, our overview focuses on ten particularly impactful ones from five major eras in American History:

- Part 1: The Founding Era covers George Washington and Andrew Jackson, two presidents essential to the creation of American democracy as we know it today.

- Part 2: The Civil War and Reconstruction describes Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, two of the presidents who oversaw the American Civil War and its aftermath.

- Part 3: The Progressive Era discusses Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, presidents who guided the country through major upheavals and reforms.

- Part 4: The Cold War looks at John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, two figures who altered how people viewed the presidency.

- Part 5: The 21st Century covers George W. Bush and Barack Obama, presidents who led the country in a rapidly changing modern world.

In our overview of O’Reilly and Dugard’s book Confronting the Presidents: No Spin Assessments From Washington to Biden (published in 2024), we cover the authors’ observations of the presidents’ personal lives and presidential legacies.

(Shortform note: We’ve chosen to focus on some of the more notable, impactful presidents. But why are some so much more impactful than others? The answer has a lot to do with how the job has changed over time. The Founding Fathers didn’t give the president much power when they wrote the Constitution. Early presidents required congressional approval for nearly all foreign policy decisions and weren’t in charge of any major federal bureaucracies. Apart from a few exceptions—which we cover in this overview—most presidents accepted this arrangement until well into the 20th century. This means that a lot of the less remembered presidents simply couldn’t do nearly as much.)

Part 1: The Founding Era

The first few decades of American history were full of uncertainty. Would the country last? What would its political system look like? What did it mean to be president? Early US presidents helped provide answers to these questions through their public image and political decisions.

O’Reilly and Dugard suggest that two presidents set the standard of what the US presidency looked like in the beginning: George Washington and Andrew Jackson. Part one of our guide will cover the authors’ perspectives on the personal and political lives of these two men.

The First President: George Washington

After leading the Continental Army to victory in the American Revolution and securing US independence, George Washington had an even more difficult task: keeping the country together as its first president. The authors outline who he was as a man as well as the political struggles he faced.

Personal Life

The authors describe George Washington as a stoic man who loved horseback riding and the Virginia countryside where he spent most of his life. Both Washington and his wife Martha preferred a quiet life to the publicity of the White House. Washington didn’t like politics, but he accepted the role of president out of duty to his country.

To illustrate Washington’s loyalty and sense of duty, the authors highlight his difficult relationship with his mother, Mary. Washington inherited most of his father’s wealth, and Mary resented him for it. She frequently asked him for money and criticized him, while never acknowledging his accomplishments. She tried to embarrass him by complaining publicly about her poverty, even though Washington provided for her. For his part, Washington always gave her what he could and never confronted her about her hostility. Their relationship remained rocky until she died in 1789. Washington didn’t attend her funeral, as he was busy with presidential duties.

Presidency

O’Reilly and Dugard explain that Washington’s presidency faced immediate challenges. The country had massive debt from the Revolutionary War, no military, and deep political divisions. Some of Washington’s advisors, like Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, wanted a strong federal government with the power to manage the whole country. Others, like Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, wanted Washington to give power to state governments while keeping the federal government weak. Washington struggled to find compromises that both camps could agree to.

Washington’s problems came to a head in 1791 during the Whiskey Rebellion. When the federal government taxed whiskey, many farmers in the rural mountains of Pennsylvania refused to pay—and even attacked—tax collectors. Washington tried to handle the situation without force by encouraging the farmers to pay. But anti-government violence continued, and in 1794, Washington put his foot down and personally led 13,000 troops to quell the rebellion. This act demonstrated the power of the newly formed federal government.

Washington could have run for president again after his second term, the authors explain, but he was tired of political life and wanted to retire. He also believed that the US Constitution was stable enough to last without him—a belief the authors say was correct, largely because of his efforts to mediate disputes and strengthen the government.

The Seventh President: Andrew Jackson

America’s first six presidents were all either Founding Fathers or their relatives. But by the 1820s, American politics had grown beyond a few small influential families. The seventh president, Andrew Jackson, symbolized this change. The authors explain that Jackson was born poor, had limited education, and lacked the formal manners of many elites in Washington. This meant a lot of established American politicians hated him, but it made him uniquely popular among the public—ushering in a new spirit of popular democracy in America.

Personal Life

Jackson’s early life was full of tragedy: His father died before he was born, and he lost his mother and both of his brothers in the Revolutionary War. As an adult, Jackson became a lawyer despite having little formal education, served briefly in Congress, and rose to prominence as a military leader during the War of 1812 after his victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.

The authors explain that Jackson was short-tempered, and he valued honor highly. He loved fighting, gambling, and fine foods, earning the nickname “King Andrew” because of the lavish meals he ate in the White House on fine china. He spent much of his life running a large plantation in Tennessee called “The Hermitage,” and was known for being cruel to his slaves.

Presidency

Jackson’s presidency was marked by several major controversies. Most notably, he dealt with tensions between settlers and American Indian tribes in Georgia. Jackson forcibly relocated the tribes hundreds of miles west, to Oklahoma. Thousands died of cold, starvation, and disease along the route, which is now known as the Trail of Tears.

Tensions over the expansion versus abolition of slavery also flared up during Jackson’s presidency. This included navigating Texan independence. Once a territory of Mexico, Texas declared itself an independent republic in 1836 and wanted to be annexed by the United States—as a slave state. Politicians in the US were split over whether to admit Texas and whether it would have slavery, as there was a precarious balance between slave and free states. O’Reilly and Dugard write that instead of annexing Texas outright, Jackson chose to recognize it as an independent nation. This set the groundwork for US-Texan relations and future annexation, which happened several years after Jackson’s presidency.

Despite his controversial legacy, Jackson’s influence on American politics remains strong to this day. Later presidents, from Abraham Lincoln to Franklin Roosevelt to Donald Trump, have referenced Jackson’s relatable, anti-establishment style of presidency as an inspiration.

Part 2: The Civil War and Reconstruction

Now that we’ve covered two iconic presidents of early US history, we’ll turn to the presidents who oversaw one of the nation’s largest crises—the American Civil War—and its aftermath: Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.

The 16th President: Abraham Lincoln

O’Reilly and Dugard explain that before Abraham Lincoln was elected president, the US was on the verge of falling apart. Debates over slavery had triggered multiple political crises, failed compromises, and talk of seceding from the Union among several slave states. And as soon as Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860, this talk became reality, and the lead-up to the American Civil War began.

Lincoln served as president for the entire conflict. O’Reilly and Dugard delve into the character traits, decisions, and political circumstances that allowed Lincoln to win the war and reunite the country.

Personal Life

O’Reilly and Dugard explain that, despite growing up poor and losing his mother at a young age, Lincoln was intensely ambitious. He educated himself, reading whatever he could get his hands on, and rose from lawyer to state senator to congressman over two decades. In 1860, Lincoln gave a speech at The Cooper Union in New York City that caught the attention of the newly formed Republican Party. In it, he argued a moderate position—keeping slavery where it already existed, but not expanding it. What really caught the crowd’s attention was his passion and rhetorical skill, which eventually secured his victory in the 1860 presidential election.

Lincoln went through bouts of depression all his life, particularly after the death of his 11-year-old son Willie in 1862. But despite this, he fully dedicated himself to his work and the war effort. Lincoln lived a simple lifestyle without luxuries. His wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, was a close supporter, but struggled with mental illness later in life. Nevertheless, Lincoln stood by her.

Presidency

As president, Lincoln was faced with the enormous task of winning the largest war yet in American history and reuniting the country. O’Reilly and Dugard emphasize how Lincoln was able to adapt his approach over time:

While his goal was always to reunite the country with as little bloodshed as possible, he learned that decisive and sometimes harsh measures were necessary to win the war. He replaced Generals like George McClellan who proved too cautious to press their advantage. And when the public criticized General Ulysses S. Grant for his bloody campaigns later in the war, Lincoln understood the tactical importance of wearing down the rebels and let Grant continue. Above all else, Lincoln refused to accept anything but victory.

Lincoln’s most famous act as president was signing the Emancipation Proclamation, a document that started the process of ending slavery in the US. But he was never able to finish this process, or to rebuild the country, despite winning a second term as president (a secessionist assassinated Lincoln less than a week after the end of the war). Nevertheless, O’Reilly and Dugard note, many scholars consider Lincoln the greatest president in American history for ending slavery and keeping the country intact while facing the biggest crisis in its history.

The 18th President: Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was already a national hero when he became president in 1869, having led the Union military to victory in the American Civil War. However, although the war was over, the country was far from being peacefully reunited. O’Reilly and Dugard go over Grant’s attempt to rebuild an integrated South as well as his personal and political struggles.

Personal Life

Grant was born in Ohio and went to West Point Military Academy at a young age. His young adulthood was a mix of excellent military service and personal struggle. After serving with distinction in the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848, Grant resigned from the army in 1854—in part because of his drinking—and started multiple businesses that failed. When the American Civil War started, he rejoined the military and became one of its greatest heroes.

Grant wasn’t interested in politics or becoming president, but he wanted to make sure the Reconstruction of the American South succeeded—and his status as a national icon made him a popular candidate. The authors state that once in the White House, Grant was glad to leave behind the harsh conditions and isolation he’d dealt with in the military. He spent a lot of time with his family and was known for being humble and honest. Later in life, Grant lost most of his money and decided to write a series of memoirs with the popular novelist Mark Twain. He died a few days after finishing it in 1885, and over 1.5 million people attended his funeral.

Presidency

The authors explain that Grant maintained his commitment to Reconstruction throughout his presidency. His predecessor, Andrew Johnson, had angered much of Congress—and Grant himself—by being lenient toward former Confederates and refusing to enact federal legislation to rebuild an integrated South. This leniency had allowed ex-Confederate groups like the Ku Klux Klan to freely terrorize and murder newly freed Black Americans. Grant’s aggressive response, including deploying federal troops, suspending habeas corpus, and establishing new, multiracial governments, successfully weakened the organization by 1872. However, challenges like corruption and economic instability beleaguered Grant’s Reconstruction efforts.

Grant’s presidency also saw continued westward expansion and its consequences, both positive and negative. On the positive side, Grant oversaw the creation of the first national park at Yellowstone and the completion of the transcontinental railroad. On the negative side, increased expansion meant more conflicts with American Indians, despite Grant’s efforts at mediation.

O’Reilly and Dugard write that while Grant was an honest man who maintained a good reputation throughout his presidency, his administration was plagued by corruption. Scandals like the Whiskey Ring involved the people around Grant using federal money to enrich themselves and their friends.

Part 3: The Progressive Era

Now that we’ve covered the presidents who guided the US through the Civil War and its aftermath, we’ll skip ahead several decades. Following a series of relatively hands-off administrations, the Progressive Era saw presidents taking a more active approach to politics. In this section of the guide, we’ll examine two presidents who set the tone for this period: Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The 26th President: Theodore Roosevelt

O’Reilly and Dugard write that Theodore Roosevelt became president at the end of the Gilded Age, a time when unregulated corporations expanded massively in wealth and political power. Roosevelt believed these corporations had gone too far and that the government had to step in. This section will go over Roosevelt’s personality and life, as well as his major political accomplishments.

Personal Life

Roosevelt was born into a wealthy New York City family, though he always preferred sports and outdoor activities to education and high society. When he was a young man, Roosevelt’s wife and mother both died within a short period of time. Full of grief, Roosevelt moved to North Dakota to live on an isolated ranch. There, he adapted to the harsh lifestyle of the American West and developed the belief that the country should be run according to rugged, masculine values like strength, courage, and determination. The authors say he lived by these ideals himself during the Spanish-American War, when he gathered and led a regiment of volunteers known as the Rough Riders, who earned distinction for their bravery in battle.

After his military service, Roosevelt returned to politics and concerned many of the high-up politicians and businessmen in the Republican Party with his popularity and strong anti-corruption stance. O’Reilly and Dugard write that these power brokers offered Roosevelt the vice presidency under President McKinley to keep him in a position without much real power. But, in 1901, an assassin killed McKinley, and Roosevelt was suddenly president.

Presidency

As President, Roosevelt was energetic and ambitious. The authors explain that for his domestic agenda, he started the country’s first wave of corporate regulations to protect public health, the environment, and competition in the free market. This included creating the Food and Drug Administration to ensure the cleanliness and safety of food and medicine and having his Department of Justice pursue antitrust laws to break up corporate monopolies. Roosevelt also created some of the country’s first environmental protections through agencies like the Forest Service.

Internationally, Roosevelt made a point of projecting America’s power and prestige across the globe. His biggest project was the Panama Canal, a massive structure that connected the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Roosevelt also brokered a peace deal to end the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, winning a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts and highlighting the US as a major player on the global political stage.

The 32nd President: Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Two decades after Theodore Roosevelt left office in 1909, his fifth cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, or “FDR,” began the longest term of any US President to date. FDR became president during the Great Depression, the worst economic crisis in world history. Meanwhile, tensions in Europe between democratic, fascist, and communist nations were on the rise. O’Reilly and Dugard argue that, because of the way FDR handled these developments, he’s undoubtedly the most impactful president in modern American history, even though his legacy is complex and imperfect. They elaborate on the president’s character and the controversies of his presidency.

Personal Life

Much like his cousin Theodore Roosevelt, FDR was born into wealth. After receiving a prestigious education at Harvard, he married his distant cousin Anna Eleanor Roosevelt—a woman who went on to have a long, accomplished career of her own as a diplomat and activist. O’Reilly and Dugard explain that their marriage was distant, with the pair sharing little affection and living their lives separately.

According to the authors, FDR was ambitious and intellectual, and he enjoyed solitude. He was also plagued by health problems. At 39, he caught a rare adult case of polio that left him mostly wheelchair-bound. However, he trained himself physically and pushed himself to stand and walk during public appearances. Once the US entered World War II, the strain on FDR’s body increased. He slept less, using the extra time to meet with his advisors and plan. He lost weight and became weak. These stresses, combined with FDR’s lifelong smoking habit, caused his death in office at 63 by cerebral hemorrhage.

Presidency

O’Reilly and Dugard largely discuss FDR’s time in office through two major events: The Great Depression and World War II.

The Great Depression was ongoing when FDR entered office, and he attempted to stabilize the economy through a variety of new federal programs known as the New Deal. The New Deal aimed to build safety nets for the poor, create thousands of new jobs, and restore consumer confidence with projects ranging from bailouts for banks to the creation of Social Security and investments in public works projects. FDR used his control over both houses of Congress and pushed the limits of his executive power to pass the New Deal. His critics compared his left-leaning policies and desire for power to Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. But FDR remained popular, easily winning re-election in 1936, and the economy slowly recovered.

O’Reilly and Dugard explain that during the first half of his presidency, FDR tried to take a mostly neutral stance on the rise of communism in the Soviet Union (USSR) and fascism in Germany and Italy—despite growing news of human rights abuses in these countries. But when World War II began in 1939, FDR gradually changed course and supported Allied nations like France and the UK, providing resources like diplomatic pressure and weapon shipments. Eventually, this support caused the Empire of Japan—part of the Axis powers along with Germany and Italy—to launch a surprise attack on the US and bring it into the war.

FDR delegated most military decision-making to his generals, focusing on politics and diplomacy instead. O’Reilly and Dugard note that he made his most controversial decisions during this period, from imprisoning thousands of innocent Japanese Americans in internment camps to ignoring Holocaust victims in Nazi concentration camps in favor of trying to end the war quickly. He also grew to trust Stalin and wanted to peacefully divide influence over Europe between the US and the USSR—a move that O’Reilly and Dugard argue allowed the Soviets to occupy and oppress much of eastern and central Europe. FDR remained popular regardless, becoming the first and only president to be elected to four terms in office.

Part 4: The Cold War

After the end of WWII, the US and the USSR were global superpowers, and both nations engaged in a “Cold War” of economic and diplomatic competition along with espionage and warfare through proxy groups. The authors write that America’s power, along with the constant threat of nuclear war, meant that the role of president was more important than ever. In Part 4 of our guide, we’ll cover two presidents who took on these challenges in very different ways: John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon.

The 35th President: John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, or “JFK,” was the youngest man ever to become president. He took office during one of the most tense moments in the country’s history, as the Cold War threatened to heat up. JFK was a figure known for both his personal popularity and his tragic death via assassination in 1963. But O’Reilly and Dugard emphasize that beneath JFK’s clean-cut image was a chaotic personal life and a political career full of controversy.

Personal Life

JFK was born in 1917 to an influential political dynasty. His father, Joseph Kennedy—a wealthy financier and ambassador with many political connections—favored JFK’s older brother Joe Jr., grooming him for political office from a young age. Meanwhile, JFK suffered from a number of medical problems in his youth. These included chronic back pain, which led to a painkiller addiction for much of his life. When Joe Jr. died serving in WWII—O’Reilly and Dugard note that both he and JFK served despite their family’s ties to and sympathy for Adolf Hitler—Joseph decided JFK would run for office instead, spending vast sums of money on JFK’s campaigns for Congress and eventually the presidency.

While the public knew JFK as an honest, handsome young man with a happy, loving family, O’Reilly and Dugard explain that this wasn’t the case in private. They explain that JFK had countless marital affairs to the point where his promiscuity was an open secret in Washington. He even made passes at the wives of the people around him and was known as a “playboy.”

Presidency

O’Reilly and Dugard mainly focus on JFK’s foreign policy, which had two major challenges to manage. First, America’s ally South Vietnam was struggling with domestic unrest against its oppressive leader, President Ngo Dinh Diem. The country was also under attack from communist revolutionaries in the north. JFK didn’t want to expand American involvement in Vietnam, but he didn’t want to be seen as weak on communism either. O’Reilly and Dugard argue that JFK chose to take a middle path instead—ordering the CIA to assassinate Diem in the hopes that it would stabilize the situation.

JFK’s second major challenge was in Cuba, where a recent revolution led by Fidel Castro had created a communist government allied with the USSR. JFK approved a CIA plan to arm and train Cuban dissidents to invade Cuba via the Bay of Pigs and overthrow Castro in 1961. The plan failed disastrously, and the public and press blamed JFK. The following year, JFK entered a tense standoff when the USSR attempted to move nuclear missiles to Cuba—eventually forcing Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to back off.

JFK’s presidency ended suddenly when an assassin killed him in 1963, creating chaos and preventing him from pursuing his primarily progressive political plans.

The 37th President: Richard Nixon

Six years after JFK’s death, Richard Nixon became president during the height of the Vietnam War, a moment of uncertainty for the country and its role in the Cold War. But while Nixon focused on international affairs, problems at home piled up and threatened to undo him. O’Reilly and Dugard explore the complex web of Nixon’s political achievements, failures, and personality.

Personal Life

Nixon was born poor in Orange County, California, and spent much of his youth working to support his family. An excellent student, he was invited to Harvard, but chose the smaller Whittier College so he could stay in California and continue helping his parents. Nixon served in the Navy during World War II and pursued a political career shortly after, quickly rising from Congress to the vice presidency on the strength of his strong anti-communist messaging. After narrowly losing the 1960 presidential election to JFK, Nixon bided his time and gathered a coalition of conservative allies. This strategy paid off with a close election victory in 1968.

O’Reilly and Dugard acknowledge that Nixon had a reputation as a ruthless and ambitious man who had little empathy for others. But they also note that the people close to him spoke often of his intelligence, his sense of humor, and his patriotism.

Presidency

Nixon largely focused on international affairs while in office, managing—and after much delay, ending—the Vietnam War while also negotiating a thaw in relations between the US and communist China. But his presidency fell apart starting in 1972 due to the Watergate scandal, when burglars broke into and bugged the Democratic National Committee offices in Watergate, a complex of buildings in Washington, DC. Nixon denied any involvement in the Watergate scandal, and O’Reilly and Dugard suggest that while he likely didn’t know about the break-in ahead of time, he did attempt to cover it up when he learned that the burglars were connected to his political campaign committee.

The media gradually uncovered not only Nixon’s cover-up attempts but also his covert funding of other acts of political spying and sabotage. Over the course of a year, Nixon went from being the landslide victor of the 1972 presidential election to a broadly hated figure. Facing possible impeachment, Nixon chose to resign in 1974. O’Reilly and Dugard explain that Nixon left behind a legacy strongly associated with lying, cheating, and corruption in the public consciousness.

Part 5: The 21st Century

With the end of the Cold War and the rise of the internet, the 21st-century political landscape changed drastically in only a few short years. Part 5 of our guide will cover both of the 21st-century presidents who’d served their full terms by the time Confronting the Presidents was written: George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

The 43rd President: George W. Bush

George W. Bush became president during a time of peace and prosperity for the US. The Cold War was over, there was no major threat to liberal democracy in the world, and the economy was running smoothly. But all of that was soon to change. O’Reilly and Dugard explore the major twists and turns in Bush’s presidency as well as his background.

Personal Life

George W. Bush was born into a wealthy and powerful political dynasty. The son of George H. W. Bush, who served as president from 1989 to 1993, the younger Bush received a prestigious education at Yale University. Then, he served in the Texas Air National Guard to avoid getting drafted into Vietnam, and he entered politics a few years later. Bush went from a position in Congress to governor of Texas and then to president after a hotly contested election decided by the US Supreme Court in 2000.

O’Reilly and Dugard note that Bush was rumored to be a reckless young man who’d had difficulties with heavy drinking in his past. However, Bush quit alcohol entirely when he was 40 after receiving an ultimatum from his wife. O’Reilly and Dugard describe Bush as energetic and restless, and they emphasize the politeness and dignity he expressed even during the most intense moments of his presidency.

Presidency

O’Reilly and Dugard argue that the September 11 terrorist attacks defined Bush’s presidency, turning him from a controversial president to the leader of a temporarily united country. Bush acted decisively after the attacks. Within weeks, he ordered the invasion of Afghanistan in search of Osama Bin Laden, one of the main figures behind them. He described the invasion as part of a larger war on terrorism, both at home and abroad. O’Reilly and Dugard acknowledge that some of Bush’s measures to fight the War on Terror were controversial, like his use of mass surveillance and torture. But they argue he effectively improved national security.

In 2003, Bush set his sights on Iraq and its dictator, Saddam Hussein. Saddam wasn’t closely affiliated with Bin Laden or his associates; regardless, Bush decided to invade Iraq after a number of reports came out suggesting Saddam possessed nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. The US deposed Saddam in less than a month, but found no evidence of the weapons of mass destruction described in previous intelligence.

The 44th President: Barack Obama

Barack Obama became president as the war on terror was cooling off—and as the 2008 financial crisis was causing economic chaos. O’Reilly and Dugard explore both who Obama was and how he managed these evolving challenges.

Personal Life

Barack Obama was born in 1961 to Ann Dunham, an American academic, and Barack Obama Sr., a Kenyan government official. Both were students at the time, and their relationship didn’t last. Obama was primarily raised by his grandparents in Hawaii. He was an excellent student, attending Harvard Law School. From there, Obama went to Chicago to work as a lawyer and activist—a path that led him to political office. O’Reilly and Dugard explain that as a senator, Obama avoided taking controversial stances. Instead, he focused on planning for a presidential run two years after joining the Senate and became the first African-American president.

O’Reilly and Dugard describe Obama as a serious and disciplined man. They explain that he often made big, ambitious plans in and out of office. He faced a great deal of criticism during his political career, including doubts about his American citizenship—doubts that O’Reilly and Dugard argue are unfounded.

Presidency

O’Reilly and Dugard largely tell the story of Obama’s presidency through two of his major political projects, neither of which completely succeeded or failed: Obamacare and ending the war in Iraq that his predecessor, Bush, had started as part of the War on Terror.

Obamacare, officially known as the Affordable Care Act, was Obama’s landmark piece of legislation to expand the government’s role in providing healthcare. O’Reilly and Dugard argue that while Obamacare did provide many low-income Americans with health insurance, critics viewed it as government overreach. The authors suggest this backlash cost Obama both the House and Senate in the 2010 midterm elections, halting a lot of his political momentum, and that it contributed to increased political polarization throughout the 2010s.

Obama also wanted to withdraw all American soldiers from Iraq, preferring to fight the War on Terror with smaller tactical strikes and raids like the one that killed September 11 architect Osama Bin Laden in 2011. However, a civil war in Iraq’s neighbor Syria, as well as the rise of terrorism in the region controlled by the Islamic State (ISIS), led Obama to redeploy troops to both Iraq and Syria.