This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Gene" by Siddhartha Mukherjee. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How long have we been studying genetics? What were the most significant events in the history of the field?

The word “gene” was coined by Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen in 1909. However, crucial strides in the field of genetics had been made before that term even existed.

Keep reading to learn about the scientists that laid the groundwork for the study of genetics.

Darwin’s Theory of Evolution

The history of genetics dates back to 1859, when Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution, titled On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (commonly shortened to The Origin of Species). Darwin developed his theory by studying finches in the Galapagos Islands, where he found that birds on different islands had distinctly different beak shapes—for example, one beak type was well suited for cracking open nuts, while another was effective at digging insects out of tree bark.

Darwin concluded that each type of finch had evolved to thrive in its particular environment. This happened because traits that help organisms survive and reproduce tend to get passed on to the next generation, while less suitable traits tend to get outcompeted and die out. In this case, because the conditions on each island were slightly different, over time those traits diverged and created noticeably different types of finches.

However, Mukherjee tells us that while Darwin accurately explained the results of evolution, he wasn’t able to figure out how it worked. Darwin (incorrectly) proposed small “particles” of inheritance produced by cells and carried in the blood, which he called gemmules.

Darwin theorized that streams of these particles from each parent would mingle in their offspring, thereby blending the parents’ traits. He called this theory pangenesis (meaning “originating from everything”) to illustrate that any given gemmule could come from anywhere in the body.

He also believed that, because any cell could produce gemmules, those gemmules would carry information about changes that cell had undergone—for instance, injuries, or muscles made stronger through a lifetime of exercise. In other words, pangenesis theory relied in part on the inheritance of acquired characteristics, rather than purely genetic ones.

Mendel’s “Unit of Heredity”

In 1864, not long after Darwin published The Origin of Species, biologist and Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel made another major breakthrough in genetics (although that word didn’t exist yet). By breeding and studying pea plants with obviously different traits—such as different heights, different colored flowers, and so on—he discovered clear patterns of inheritance across generations.

Most importantly, according to Mukherjee, Mendel discovered that traits would be passed on completely; for example, if he cross-pollinated a purple-flowered plant with a white-flowered plant, the offspring would have purple flowers. This ran counter to the popular theory of Mendel’s time that traits would “blend” during inheritance, in which case that plant would end up with pale purple flowers, or some purple and some white.

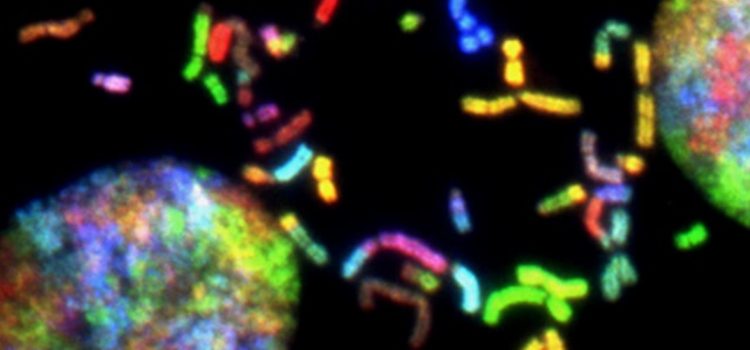

If traits get passed on completely intact, Mendel reasoned, then there must be a “unit” of heredity: self-contained packets of genetic information representing a single trait—which Mendel called factors—rather than a stream of particles mixing with other streams like Darwin proposed.

| Mendel’s Laws of Inheritance Aside from his concept of a unit of heredity, Mendel is credited with creating two “laws” that describe patterns of inheritance: The Law of Segregation. Organisms have two copies of each gene—one from each of their parents—which may be different from one another. When an organism reproduces, it randomly passes on one gene from each pair. The Law of Independent Assortment. Genes are passed on to offspring independently of each other. In other words, offspring inheriting one trait doesn’t guarantee they’ll inherit a different trait—blond hair doesn’t always go with blue eyes, for example. |

de Vries Fills in the Gaps

Mukherjee recounts that in the 1890s, Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries made the next major step toward modern genetics by recognizing that a self-contained unit of heredity perfectly explained Darwin’s observations of how species evolve. In other words, Mendel and Darwin’s discoveries were both parts of a single, cohesive theory of evolution.

De Vries added one point of his own to this theory: There must be a chance, however small, that genetic information could spontaneously change during reproduction. In other words, de Vries introduced the concept of mutations.

Mutations are a critical part of evolutionary theory because evolution requires diversity—natural selection can’t “select” genes that don’t exist—and without mutations, there would be no way for new traits to appear. For example, Darwin’s finches couldn’t have developed different types of beaks unless there were already slight beak differences coded into their genes.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Siddhartha Mukherjee's "The Gene" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Gene summary:

- What genes are and how they work, explained in simple terms

- The history of gene discovery, dating back to the 1800s

- What the future of genetic engineering looks like