This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "NeuroTribes" by Steve Silberman. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Who was Bernard Rimland? How did his autism research change how some saw the disorder? What were some of the problems with his theories?

Bernard Rimland was an American psychologist in the mid-1900s. It was thanks to Rimland that parents were no longer blamed for causing autism, however, Rimland also promoted the idea that vaccines caused autism.

Continue reading to learn about Bernard Rimland’s research and its impacts.

The Work of Bernard Rimland

According to Steve Silberman in NeuroTribes, the theory that poor parenting causes autism prevailed in the medical field until the 1960s, when Navy psychologist Bernard Rimland (who had an autistic son) published a book arguing that autism wasn’t caused by childhood trauma but was instead a genetic disorder.

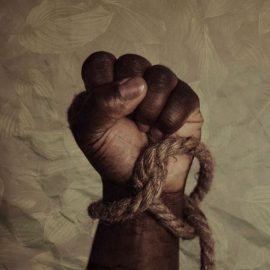

Rimland’s book took the blame for autism off of the parents, Silberman explains. It also took the experiences of autistic children into account in a way that had rarely been done before: Rimland theorized about what it was like to exist in a world not built for them and sympathized with the frustration that must come from meeting all the seemingly arbitrary demands of adults whose brains worked differently. However, not all of his work holds up to modern scrutiny, as we’ll see next.

(Shortform note: As Silberman asserts, parents don’t cause autism. However, experts explain that with the right training, they can help improve their children’s lives. Research suggests that training parents in how to communicate with their autistic children can help reduce symptoms like anxiety and aggression. Additionally, participating in cognitive behavioral therapy with their autistic children can improve parents’ mental and emotional well-being.)

| The Interplay Between Autism and Trauma The attribution of autism to childhood trauma—a myth Rimland helped dispel—is further complicated by the fact that autism and trauma are often hard to distinguish. For one thing, the symptoms of trauma-related conditions like PTSD often mirror some of the symptoms and traits of autism—for example, increased sensory sensitivity and difficulty regulating emotions. Additionally, autistic people are more likely than allistic people to experience trauma, and trauma survivors are more likely to experience further trauma, making both groups especially vulnerable. Autistic people’s sensitivities can also cause them to be traumatized by events that allistic people wouldn’t find traumatizing. All of these factors can lead to misdiagnoses of PTSD and autism (mistaking one condition for another) and missed diagnoses (correctly diagnosing one condition while overlooking a co-occurring one). |

Rimland’s Problematic Theories

While much of Rimland’s work helped progress the field of autism research, he also promoted other, ultimately harmful theories, Silberman explains. For instance, Rimland agreed with Kanner’s strict definition of what constituted autism and believed it wasn’t a spectrum. He also posited that while autism was genetic, environmental factors such as diet and metabolism could exacerbate it. This began a movement known as the biomedical movement (or BioMed for short). This movement was devoted to “curing” autism through dietary changes (like gluten-free or ketogenic diets), supplements, medication, and chelation (the use of drugs that bind to toxic metals in the blood, allowing the body to then flush out the toxic metals).

Rimland also promoted the idea that vaccines caused autism. Though it’s since been debunked, this idea gained greater traction in the late 1990s, when gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield published a paper claiming that chemicals in the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine had caused an autism epidemic. The paper cited a study that was later retracted due to its unreliability and inaccuracies, and Wakefield lost his medical license for spreading fraudulent information.

Furthermore, the apparent “autism epidemic” that Wakefield cited wasn’t due to an increased incidence of autism. Rather, increasing autism rates were due to expanded diagnostic criteria and a better clinical understanding of the disorder. Thus, vaccination rates had no effect on autism rates.Still, the paper led to a worldwide drop in vaccination rates, resulting in a massive resurgence of diseases that had nearly been eradicated.

| Why We Cling to the Theory of Environmental Causes Despite its thorough debunking, the idea that vaccines and other environmental factors cause—or might cause—autism persists to this day. Proponents of this idea argue that the expansion of diagnostic criteria alone isn’t enough to explain the increase in diagnosis rates. They add that, whether or not you believe in environmental causes of autism, BioMedical interventions like dietary changes can’t hurt (though some research and critics suggest otherwise). Other researchers contend that the reason many still cling to the idea of environmental causes is because we haven’t yet identified the specific genetic cause of autism, and this uncertainty makes parents and carers of autistic people uncomfortable. It’s more reassuring to hear a decisive (though false) statement like “Vaccines cause autism” than to be told, “We haven’t yet identified the precise mechanism that causes autism.” However, as research progresses, science is getting closer to identifying a clear biological cause. A 2019 study suggests autism may be caused by a gene mutation that impairs the development of synaptic connections (the connections between brain cells) at an early age. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Steve Silberman's "NeuroTribes" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full NeuroTribes summary:

- The truth behind the common misconceptions about autism

- How society’s perception of autism has evolved since the 1930s

- The most effective treatments for autism spectrum disorder