What should you do before you read a work of nonfiction? How can reading more content actually help you read faster?

The authors of 10 Days to Faster Reading offer this surprising speed-reading strategy: Familiarize yourself with the content before you begin. It might seem like you’re taking unnecessary extra time, but you’ll be able to read faster—and with more comprehension—when you take this step.

Let’s take a closer look at this reading strategy.

Before You Read

According to the authors, it’s helpful to briefly familiarize yourself with the content of a nonfiction text before you start reading in earnest. (Shortform note: In How to Read a Book, Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren describe inspectional reading, a similar process for previewing a text. It’s the second of their four reading levels, and its purpose is to understand the structure and the main points of a text. That way, you have the background knowledge and context you need to efficiently process the information before you read the body of the text in depth. They advise setting a target of 15 minutes to gain an overview of a 300-page book.)

In addition to assisting you with Strategy #1 (be selective about what you read), this strategy helps you meet the following three goals:

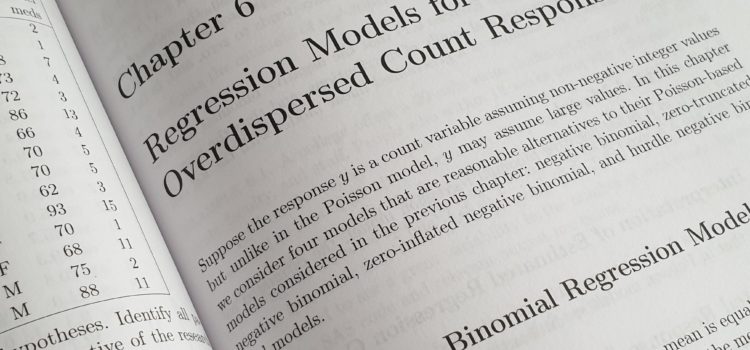

1) Getting a sense of the structure and topics covered. Almost all nonfiction writing follows an internal outline that offers a map of the topics covered. This strategy takes advantage of that framework to give you a clear overview of what you’re about to read.

(Shortform note: The internal outline is also important in nonfiction texts because it helps readers understand the author’s narrative thread throughout the piece. If a text has a clear structure, readers can follow the main points and argument without getting lost in the details. A lack of a clear outline and the author going off on too many tangents can undermine the main point of the piece.)

2) Improving your reading efficiency by giving you context and direction for a text. When you don’t familiarize yourself with a text beforehand, you don’t know where it’s going. Therefore, you may be unsure what you’re supposed to get from it. This often makes it more difficult to concentrate and understand what you’re reading. As you struggle to figure out what you’re supposed to be learning, you read more slowly.

(Shortform note: Some research suggests that looking over a text before reading improves comprehension as well as efficiency. Previewing allows you to connect the broad ideas you see in the text to any prior knowledge you have of the subject, aiding in your understanding of the ideas once you begin fully reading.)

3) Reviewing a text after reading it previously. (Shortform note: This could be particularly useful when studying or reviewing information in advance of a meeting or presentation.)

To pre-familiarize yourself with the contents of your nonfiction reading material, the authors suggest identifying and reading certain elements of the text before working through its main body. We’ll highlight two sets of elements here: 1) the title, introduction, headings, and conclusion, and 2) details about the author and the book’s copyright.

The Title, Introduction, Headings, & Conclusion

According to the authors, reading the title provides your first clue of what the text covers. Then, read the introduction (usually the first paragraph or paragraphs of the text). Once you know where the text is going, move on to the headings, which communicate the text’s content and structure. Finally, read any concluding paragraphs at the end of the text—these will often offer a synopsis of the main ideas.

| Further Thoughts on the Roles of Titles, Introductions, Headings, and Conclusions Title: In How to Read a Book, Adler and Van Doren state that a title’s usefulness for understanding what a book is about varies. Some titles tell the reader exactly what to expect from a book (like Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist). However, many modern titles are less explicit (like Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink). Introduction: According to other reading experts, introductions are important because they often contain definitions of key terms and other important context you need to understand the book’s ideas. Without this knowledge, you might be lost as you read. Headings: When you move on to the headings, consider using them to organize any notes you take. Copy them down and write your notes for each section under the correct heading or subheading—this will help you figure out what information goes with what point when you review the notes later. Conclusion: Finally, in addition to being a summary of the author’s main points, a conclusion typically offers important takeaways from the text. This is where the author lets you know why their ideas should matter to you after you stop reading, how their ideas connect to larger issues, and how to apply their ideas to your life. |

Author & Copyright Details

According to the authors, details about the writer of a piece offer insight into their unique perspective. For instance, background about their life may indicate why they’re writing about the topic.

(Shortform note: You can typically find details about an author near the end of a book, on the back cover, or on the left inside flap of the dust jacket. When reading an article, you can often find this information at the end of the text. If you want to learn more about an author’s point of view and their reasons for writing, consider also looking outside of the text for information about them. For example, visit their website if they have one, or look at their accounts on social media sites like Instagram and Goodreads. If an author is dead, look up biographical information about them.)

The authors also recommend inspecting the book’s copyright details, as they tell you when it was written. This will give you historical context.

(Shortform note: Historical context offers insight into many aspects of a text, including the style of the language and vocabulary used, the contemporary social issues influencing the text, the historical and literary references included, the behavior of characters, and so on. In the case of non-fiction works, copyright information indicates how many editions of a text exist and the most recent publication date. You can use this information to determine how relevant a text might be in relation to the most recent developments in the subject it discusses.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of The Princeton Language Institute and Abby Marks Beale's "10 Days to Faster Reading" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full 10 Days to Faster Reading summary:

- Speed-reading techniques to help you learn more efficiently

- How to rid yourself of the common unhelpful reading habits

- How to teach your eyes to take in more information at once