PDF Summary:Presence, by Amy Cuddy

Book Summary: Learn the key points in minutes.

Below is a preview of the Shortform book summary of Presence by Amy Cuddy. Read the full comprehensive summary at Shortform.

1-Page PDF Summary of Presence

Have you ever felt anxious about a new social situation, an interview, a performance, or another environment where you lack confidence? In Presence, social psychologist Amy Cuddy explains how to navigate these stressful scenarios by embodying “presence”—a self-assured confidence that’s not arrogant but allows you to comfortably express your true self. She says you can achieve presence by leveraging the body-mind connection to change the way you feel about yourself rather than worrying about what others perceive.

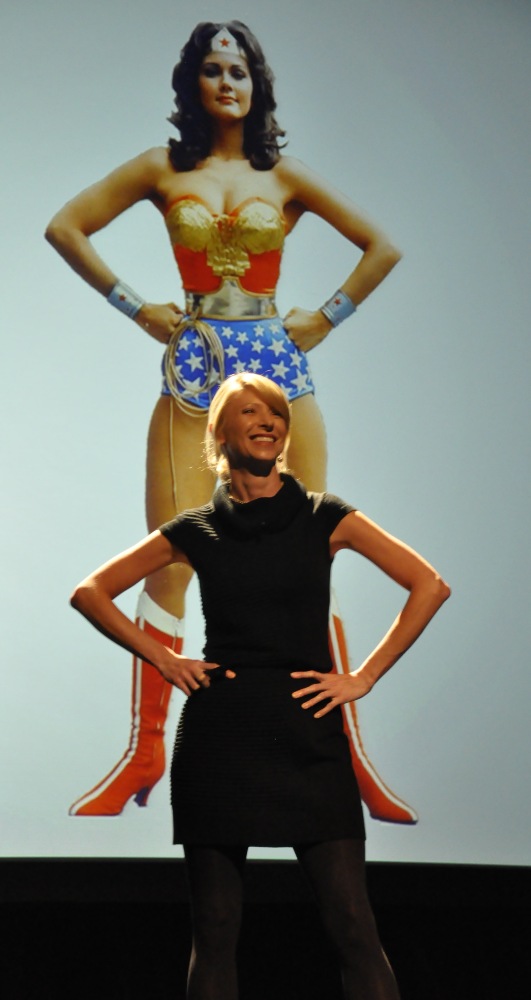

In this guide, we’ll explore Cuddy’s popular research on how “power poses”—like the superwoman stance—and other body language shifts can boost your confidence and improve your performance in high-pressure situations. We’ll also explain how research on this topic has evolved since the book was published and include tips from other experts on how to navigate stressful experiences.

(continued)...

(Shortform note: Cuddy’s concept of achieving presence by affirming your strengths and priorities is similar to other authors’ advice for cultivating confidence. For example, in High Performance Habits, Brendon Burchard says that to be confident you must have a clear self image so that you can then decisively pursue that vision. He says you can acquire this trait—what he calls “congruence”—by defining your values and setting intentions before you begin an endeavor. Burchard’s other two attributes of confidence include interpersonal connection (which presence also encourages), and competence (which Cuddy doesn’t include as a prerequisite for presence).)

The other major component of Cuddy’s advice hinges on the link between your mind and body and the idea that you can improve your mindset by changing your body language. She explains that the body-mind link is two-way: For example, when you feel embarrassed, your face flushes red—a physical response to the emotion. But when you change your posture to exude confidence—by relaxing your shoulders, for instance—your emotions also take cues from your body, and you start to genuinely feel more at ease.

(Shortform note: Because of this two-way connection, many wellness experts recommend the reverse of Cuddy’s advice: Improve your physical health by changing your mindset. For example in Ikigai, Héctor García and Francesc Miralles recommend managing your stress to prevent conditions such as premature aging and high blood pressure. Their advice for achieving mental resilience is to embrace two principles from Japanese culture: wabi-sabi—finding beauty in imperfection) and ichi-go ichi-e—recognizing that the current moment is fleeting.)

In this section, we’ll break down the best ways to use body language to your advantage before a nerve-wracking situation, how to carry yourself during a challenging situation to enhance your presence, and how you can build presence in the long term through small changes to your body language.

Before the Challenging Scenario: Power Pose

Cuddy’s advice to calm the mind and increase self-assurance before a difficult performance or experience is to find a place to “power pose,” or adopt a physical stance that increases the feeling of presence (or simply the feeling of being “powerful” as researchers often refer to it). For example, raise your arms up in a v-shape, place your legs shoulder-width apart, or put your hands on your hips. You can also put your own spin on power poses and create your own—the important part is that they make you expand your body outward and foster a feeling of power:

(Shortform note: Since Cuddy’s 2012 TED talk on power posing, the phrase “power pose”—coined in her 2010 research article—has integrated into popular culture. It has an entry in the Cambridge Dictionary, and some people speculated that Cuddy’s TED talk inspired politicians in the UK to strike power poses at high-profile events. Power posing also continues to be frequently listed on advice websites as a way to boost your confidence.)

The simple act of making yourself bigger—or even louder—is an expression of power recognized throughout the world and among both animals and humans. By extending your limbs, lifting your head, and raising your voice, you can bypass the negative thoughts fueling your anxiety and essentially trick your brain into feeling confident.

(Shortform note: In 12 Rules for Life, Jordan Peterson explains that it’s beneficial for animals to jockey for higher positioning on a social hierarchy through displays of dominance because it helps distribute scarce resources while avoiding combative conflict. For example, if two animals both want to hunt for food in the same area, they can make themselves look big, size each other up, and decide who’s most likely to win a fight. If one of them then backs down, they can both avoid injury or death. Peterson says that humans still have the biologically ingrained tendency to monitor signals of dominance (such as physical stature) to figure out social positioning, which may explain why power poses trigger confidence.)

Cuddy’s research on this topic found that power posing for a few minutes not only led to perceived feelings of greater confidence and agency in the subjects but also physically changed their hormone levels in a beneficial way. First, it elevated testosterone levels—the so-called “dominance hormone” that is both caused by and causes more assertive behavior. Second, it reduced cortisol levels, a hormone produced as a bodily stress response. Together, high levels of testosterone and low levels of cortisol are associated with more powerful people—they tend to be associated with successful leaders, for example.

And what if you’re physically unable to power pose? Cuddy adds that even if you can’t find a comfortable place to power pose before your big presentation or if you’re physically unable to do it, you can still benefit from power posing mentally. Research has demonstrated that simply visualizing yourself in a power pose can have the same effects as the physical exercise. (Shortform note: Although most studies have focused on physical power posing, rather than visualization of power poses, some research suggests that visualization techniques enhance performance and self-confidence for athletes—results that may be applicable to the many high-pressure contexts that Cuddy describes.)

Controversy Over Power Posing Research

Amid ongoing debates about the effects of power posing among researchers, social psychologists continue to refine the studies on this phenomenon to determine how high-power or low-power poses impact our behavior, mindset, and physiology. Here, we’ll describe how some of the controversy surrounding Cuddy’s work has unfolded.

Cuddy’s research on the effects of power posing initially received widespread acclaim—she was featured on major media outlets such as CNN, Oprah, and TED. However, over the next several years, some researchers criticized the results of her original 2010 power posing study, arguing that Cuddy and her colleagues may have selectively reported data and pointing out that subsequent studies by other researchers failed to replicate the results. In 2016, the main author on the initial study, Dana Carney, stated that she no longer supported the conclusion from the study due to her updated analysis of the evidence.

This evidence includes studies that found no statistically significant hormonal effect of power posing. In a 2017 interview, Cuddy stated that she’s currently undecided on whether the hormonal effects are significant, since there are wide variations in the methodologies researchers use to assess and analyze these metrics. For example, some researchers use blood samples to measure hormone levels while others use saliva samples, which can lead to discrepancies in the analyses.

However, Cuddy maintains that power posing at least increases feelings of power in individuals, which can increase their performance. A 2018 study by Cuddy reviewing 55 studies on power posing, and a 2022 study reviewing 88 studies on power posing both support the finding that high-power poses significantly enhance people’s mood, attitude, and self-esteem. The effects of power posing may also be greater when comparing a high-power posture to a low-power posture as opposed to comparing the power pose to a neutral posture.

In addition to the debate over her research, some of the criticism Cuddy received was targeted more at Cuddy as a person. For example, some critics railed against the amount of money she made from her book and speaking events. Some argue that this kind of backlash may have stemmed from people’s resentment toward successful, ambitious women and her popularity outside of the academic sphere.

During the Challenging Scenario: Adopt Open and Friendly Body Language

Although the power pose technique helps put you in a positive mindset before a high-pressure scenario, adopting overtly powerful body language while interacting with others is likely to be off-putting to them because it comes across as domineering. Therefore, in stressful situations, Cuddy recommends adopting open and friendly body language that communicates your self-assuredness without making people feel uncomfortable or defensive.

(Shortform note: Some elements of body language can also be interpreted differently depending on the context, making it important to “read the room,” so to speak. For example, standing with your hands on your hips could be interpreted as aggressive in one scenario, or it could be perceived as a sign that you’re enthusiastic and ready to go.)

Research shows that people perceive friendliness and trustworthiness before they assess your competence, so the right body language is more important for making a good first impression than showing how knowledgeable or talented you are.

To demonstrate open and friendly body language, stand up straight with your head up and shoulders back and relax your muscles. Cuddy also recommends making slow, deliberate movements when communicating. For example, if you’re on a stage, walk around slowly and use the whole space (which is also more dynamic and interesting for the audience to watch). Take your time and pause both your movements and speech when it feels right. Smiling when appropriate will make you feel better and also communicate kindness toward the other people present.

The Importance of Nailing a First Impression

Similar to Cuddy, many authors emphasize the importance of a positive first impression. For example, in How to Talk to Anyone, communication expert Leil Lowndes asserts that people rely on body language to instinctively form an opinion on someone before they even begin speaking. In How Highly Effective People Speak, public speaker Peter D. Andrei adds that people’s initial impression of you will influence their long-term perception of you because of a bias known as the halo effect: the tendency of people to generalize their opinion of someone based on one observed quality.

To optimize a first impression, Lowndes and body language experts Allan and Barbara Pease (The Definitive Book of Body Language) recommend additional open body language cues such as raising your eyebrows slightly to show that you’re happy to engage in conversation, keeping your arms loosely at your sides with your wrists and palms upward, and turning your body completely toward your listener.

Body Language to Avoid

In addition to these tips, Cuddy provides some body language to avoid, including excessive eye contact, very strong handshakes, and exaggerated, rapid, or loud movements. If you’re seated, remember not to splay your limbs all over the place like you would if you were power-posing before the event. Research shows that these behaviors tend to make people resent you because they’ll think you’re either trying to exert control over them or are being manipulative to get the results you want.

(Shortform note: It’s also important to note that while this advice is based on American culture, people’s preferences for body language vary widely by culture, so it may be necessary to account for other factors when modeling appropriate body language. For example, one source asserts that people from Asian cultures prefer more personal space than Americans, while people from Latin and Middle Eastern cultures require less personal space. Body language cues such as eye contact and handshakes may also vary depending on the relationship or gender of the people involved and can differ based on an individual’s personality.)

Cuddy writes that people tend to notice when your apparent stress and nervousness don’t match your body language—a phenomenon called “asynchrony”—which also makes you seem insincere and untrustworthy.

(Shortform note: Here, Cuddy suggests that if you use overly confident or aggressive body language to compensate for your nervousness, people will pick up on the fact that it’s not genuine or perceive it as “pseudo-confidence”. However, she doesn’t explain why people wouldn’t register asynchrony when you’re feeling nervous and you use some of the relaxed and open body language cues that we described earlier in the section. This may be why it’s important to boost your confidence with power poses before the activity so that relaxed posture comes more naturally.)

On the other end of the spectrum, tense and closed-off body language (what Cuddy refers to as “powerless posture”) to avoid includes folding your arms and legs inward, tightening your throat muscles (which raises the pitch of your voice), speaking too fast, and keeping your upper arms glued to your sides while only your lower arms move (Cuddy calls this “penguin arms”). These behaviors betray nervousness, which may make people skeptical of what you’re communicating. In other words, if you don’t have confidence in what you’re saying, neither will other people.

(Shortform note: In a sales context, some experts recommend using other people’s closed-off body language as a signal that a prospective buyer is feeling skeptical or unreceptive to what you’re saying. In The Psychology of Selling, Brian Tracy writes that if a prospective customer is crossing their arms, for example, they may be feeling closed-minded. He also says that you can subtly nudge their mood by giving them something to hold or giving them an activity that will force them to uncross their arms.)

Increase Presence in the Long Term Through Small Changes

Cuddy says that in addition to modifying your body language before and during difficult situations, you can enhance your natural feelings of presence in those moments by making powerful postures habitual in your daily life—and conversely, reducing the time you spend in postures that reinforce anxiety and negative self-views. Being intentional about small adjustments to your posture can build over time into drastic improvements in your confidence and ability to express yourself.

(Shortform note: Many experts apply this same philosophy of accumulating small wins to work toward bigger change over the long term in other contexts. For example, in Essentialism Greg McKeown describes this as a strategy that enables companies to celebrate progress, motivate employees, and create momentum when working toward a major goal. In Black Box Thinking, Matthew Syed refers to this method as a way to tackle large societal problems such as a poor economy.)

Check and Adjust Your Posture

One way to improve your presence long-term is to create reminders for yourself to check your posture and ensure that you’re not slouching or making yourself small. Reminders can be visual notes, alerts on your phone, or prompts from friends to adopt a relaxed and open posture, as we described earlier in the section. Cuddy says that the more time you spend intentionally exhibiting this kind of body language, the calmer and more confident you’ll feel on a daily basis.

(Shortform note: Although reminders may be a good start to increase your awareness of your posture, there are also other strategies you might consider for targeting the root causes of hunched posture. For example, a physical therapist could help you determine if your poor posture is a result of injury, a genetically inherited condition, or even the shoes you wear, which can shift your body out of its natural alignment.)

A major challenge of maintaining open body language is that when you spend much of your time looking at small screens—such as a smartphone or laptop— this naturally causes you to hunch your shoulders and tilt your head downward (a position Cuddy refers to as “iPosture”). One clinician observes that more people are developing dowager’s humps (a permanent curve in the upper back from slouching), and Cuddy’s research suggests that caved-in posture from looking at devices makes people less assertive and less proactive compared to when they have more open, confident posture.

(Shortform note: Research supports the idea that looking at mobile devices can contribute to poor posture and upper body strain. However, since musculoskeletal problems can arise from a wide range of conditions, it may be important to consider other factors that may be contributing to poor posture and subsequent changes in disposition. For example, these can include heavy lifting, doing any kind of repetitive motion, staying in the same position for long periods, overuse of certain muscles, or genetics that cause a higher risk for conditions such as arthritis.)

Cuddy’s tip for counteracting the closed-off body language that some devices encourage is to arrange your commonly used spaces to facilitate looking up and stretching out. For example, you might mount your TV high on the wall or use high shelves that you have to reach up to access.

(Shortform note: If you work on a computer for several hours at a time for your job, caved-in posture can cause chronic neck, back, and wrist pain in addition to negatively impacting your confidence. Some health experts recommend avoiding these physical stressors by making ergonomic adjustments to your office setup that are similar to Cuddy’s advice for rearranging your spaces. For instance, make sure that your chair supports your spine, position your armrests, keyboard, and computer mouse so that your shoulders are always relaxed, and keep your monitor or laptop at eye level between 20-40 inches away from you. Another habit that can help with these problems is getting up to move around at regular intervals. )

Practice Yoga and Controlled Breathing

Cuddy’s next advice for incrementally improving your presence is to practice yoga or another physical activity that involves stretching and controlled breathing. Research shows that this habit is particularly beneficial for people suffering from post-traumatic stress (PTS), who may experience debilitating anxiety, fear, self-doubt, and other feelings of powerlessness on a regular basis. Cuddy says that yoga enhances your presence—in addition to providing a myriad of other health benefits—because it activates the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS).

The PNS is essentially the opposite of the fight-or-flight response that arises when you feel threatened. When the PNS is activated, your heart rate slows and your mind and body enter a state of relaxation. According to many studies, doing yoga trains your body to resist automatic stress responses and can lead to long-lasting improvements in your self-esteem and mental well-being. And if you’re not interested in yoga specifically, taking slow, deep breaths, chanting, and meditating all have similar benefits.

(Shortform note: Activating the PNS through yoga and other relaxing activities is not only helpful for increasing your presence but also vital to your physical health. Activation of the PNS is the body’s way of entering a state where it can focus on digestion, healing, and physical rejuvenation. Some experts assert that hectic lifestyles—like being busy all the time—reduce the activity of the PNS and increase our stress response controlled by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). When the SNS is overactive, this imbalance can result in insomnia, digestive problems, and chronic inflammation. This stress response may also explain why people with PTSD have a higher risk of physical health problems in addition to mental health symptoms.)

Want to learn the rest of Presence in 21 minutes?

Unlock the full book summary of Presence by signing up for Shortform .

Shortform summaries help you learn 10x faster by:

- Being 100% comprehensive: you learn the most important points in the book

- Cutting out the fluff: you don't spend your time wondering what the author's point is.

- Interactive exercises: apply the book's ideas to your own life with our educators' guidance.

Here's a preview of the rest of Shortform's Presence PDF summary: