Markets swing, jobs disappear, or investments suddenly lose value. When the cards seem stacked against you, how do you manage financial risk? This article breaks down what financial risk really is and what you can do about it—whether you’re worried about permanent loss, uncertain returns, or unexpected life events that could drain your savings.

To guide you, we’ve compiled advice from several books that dive into financial risk management. Together, these sources outline practical strategies—from defensive investing to smart insurance choices—that help you avoid costly surprises and make decisions with clearer judgment.

Table of Contents

Editor’s note: This article is part of Shortform’s guide to saving money. If you like what you read here, there’s plenty more to check out in the guide!

What Is Financial Risk?

Before learning how to manage financial risk, you first need to understand what it is. In The Most Important Thing, Howard Marks clarifies that the real risk of investing is the possibility of permanent loss—based on his own investing experience, he argues that this prospect most worries investors.

The upshot is that risk can’t be objectively measured, and only investors with careful qualitative analysis can discern the risk associated with a given security. In particular, Marks argues that investors must ascertain how stable a security’s intrinsic value is, along with the nature of the connection between this value and the security’s market price. After all, these are the two factors that determine the likelihood of loss: If a security’s value dips, or the market fails to accurately reflect this value, investors will lose money.

The Best Financial Risk Management Strategies

Life is unpredictable and full of financial risks. After all, you never know when the economy might turn and cause you to lose your job, or a market downturn will deflate the value of your assets. But you can avoid falling into a financial hole with several strategies of risk management—careful investing and insurance. We’ll explore all of these strategies next.

Strategy #1: Accept Responsibility

Killing Sacred Cows by Garrett Gunderson says traditional financial wisdom holds that high-return investments require high risk—in other words, you have to risk catastrophic losses to reap extraordinary returns. This happens because investors won’t accept greater uncertainty unless they’re offered the possibility of greater rewards. For example, say you have two investment options: a low-risk government bond that guarantees 3% annual return, and a high-risk startup stock that might return 15% or might lose 50%. You’d only choose the risky startup stock because it offers the potential for much higher returns than the safe government bond.

(Shortform note: The relationship between uncertainty and rewards is known as the risk premium. In the example above, the extra potential return (the difference between a 15% return and a 3% return) is the risk premium—the additional reward investors demand for taking on additional risk. Risk premiums take into account several factors, including the uncertain cash flow of the company you’re investing in and political uncertainties.)

But, Gunderson writes, this logic is flawed because there’s no such thing as a “high-risk investment.” He argues that risk isn’t inherent to specific investments—instead, both risk and returns are functions of how much knowledge you as an investor bring to the table. You’re responsible for acquiring that knowledge and using it to inform your investments. If you experience losses, it’s not because “the market or investment is risky,” but instead because you invested without sufficient knowledge or control.

Buying into this philosophy encourages you to prioritize your financial education before making investment decisions, seek investments where you can actually affect the outcomes instead of just passively accepting them, and understand how value is being created with every dollar you invest. This approach, writes Gunderson, is empowering: It puts you in the driver’s seat of your financial future and encourages you to invest in yourself through knowledge, education, and experience.

Strategy #2: Don’t Try to Self-Insure

Now, let’s discuss other kinds of financial risks—the kinds that come from economic downturns and personal catastrophes, leading you to lose income or assets (for example, a medical condition forces you to leave your job). Garrett Gunderson writes that if you’re looking to reduce this kind of risk, you’ll need to have a smart approach to insurance. After all, the whole purpose of insurance is to reduce risk by paying a small, certain amount (your monthly premium) to avoid potentially losing much more later if catastrophe strikes.

Gunderson notes that many people convince themselves they no longer need insurance once they reach a certain net worth because they’re “self-insured.” In other words, they believe that they’ve stockpiled enough assets to cover potential losses without the need to purchase traditional insurance policies. But this approach is flawed for two reasons, according to Gunderson.

First, when you hold your own money in reserve instead of buying insurance, what you’re really doing is preventing that money from being invested in growth opportunities where it might generate returns. In many cases, the returns you’d have likely earned from investing that money would be significantly higher than what the insurance premiums would’ve cost.

(Shortform note: Despite Gunderson’s warning against it, some financial experts write that there are valid circumstances when you’d want to consider self-insurance. It might make sense not just if you have a high net worth, but also if you don’t have major financial obligations, dependents, or future liabilities, or if you can’t qualify for traditional life insurance due to health issues. The primary benefits of self-insurance in these cases include greater control over your funds—you can invest the money you’d otherwise be spending on premiums and use the returns on your investment to reinforce your financial safety net.)

Second, foregoing insurance leaves you more vulnerable than ever to financial losses. Your self-insurance approach means that you have to spend down your own assets and absorb 100% of the losses if a catastrophic event does occur. This permanently reduces your wealth and future earning potential.

In his book Die With Zero, Bill Perkins agrees with the suggestion to use outside insurance policies to avoid risk. He acknowledges the possibility of negative unforeseen circumstances and suggests looking into insurance policies that guard against unforeseen circumstances. This will allow you to invest in experiences while minimizing catastrophic financial risks.

For example, if you’re worried about crippling debt due to medical complications, you might look into long-term care insurance (which can cover costs not covered by health insurance should you ever need help performing activities of daily living). Alternatively, you might purchase life insurance to protect your loved ones should you die unexpectedly. Perkins also suggests an annuity to guard against the ‘risk’ of outliving your money.

Strategy #3: Ray Dalio’s Risk Parity Strategy

Popularized by Ray Dalio, the founder and principal of the successful hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, “risk parity” involves taking long positions in low-risk assets—even borrowing money to do so—to increase returns. The theory underlying this strategy is that low-risk assets often boast higher returns than their risk level would indicate and that high-risk assets are often overpriced.

There are several ways to develop a risk parity portfolio, all involving buying low-risk assets on margin, according to A Random Walk Down Wall Street by Burton G. Malkiel. For example, an investor might borrow to invest in low-beta stocks or bonds. Of course, by borrowing, an investor increases his or her risk—but he or she also increases returns. An investor who bought only bonds between 2007–2016, 50% on margin, would have produced returns just under 2% better than the S&P 500 with slightly less volatility. (This example assumes no cost of borrowing, however.)

The Risk Parity Strategy and the 60/40 Portfolio

A baseline allocation for institutional portfolios—for example, retirement or pension funds—is 60% common stock, 40% bonds. The 60/40 portfolio aims to net investors the higher returns of the stock market while insuring them against market corrections with the consistency of bonds.

However, using a risk parity strategy, investors might be able to achieve greater returns with the same level of risk as a 60/40 portfolio. The way to do this is to create a portfolio whose stock/bond allocation has the same risk and return as the “riskless” rate (in other words, the interest rate on a Treasury bill), and then buy that portfolio on margin. By buying on margin, one can increase volatility to the point where it’s the same as a 60/40 portfolio but with better returns.

Another way to achieve risk parity and outperform a 60/40 portfolio is to invest in a wider array of assets. For example, Bridgewater Associates includes real estate assets (REITs), Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), and other products in its portfolios. As long as these additional assets are negatively correlated—that is, they increase the diversification of the portfolio—then risk is further minimized.

Strategy #4: Defensive Investing

Though he discourages high-risk investments, Howard Marks recognizes that eliminating risk altogether—for example, by purchasing 10-year government bonds that return around 4% annually—will yield unsatisfying returns. He argues that, to balance this inverse relationship between risk and return, you should practice defensive investing, which uses a margin of safety to reap reliable returns while minimizing risk.

As Marks relates, the margin of safety refers to the difference between a security’s intrinsic value and its market price when purchased. For example, imagine that you purchased Tesla stock at $118.47 at the beginning of 2023, and its intrinsic value was $150 per share. Then, your margin of safety would be about $32 per share.

(Shortform note: Graham, who first introduced the concept of margin of safety in The Intelligent Investor, argued that one crucial way to increase your margin of safety is through diversification (purchasing more securities of different types). He reasoned that, even with a margin of safety, investing in only one security leaves you exposed to loss if that security drops significantly. For instance, even with a $32 per share margin of safety when purchasing Tesla stock, a large drop in Tesla’s intrinsic value could leave you exposed to a loss if that was your only investment. By contrast, with a diverse portfolio, you’ll still be able to earn a profit even if some of your securities drop in value.)

According to Marks, investing based on the margin of safety has two key benefits. First, as we discussed earlier, securities purchased below their intrinsic value are likely to increase in price because market price typically reflects intrinsic value over the long term. Second, the margin of safety protects investors from loss if the intrinsic value of a security decreases. Returning to the previous example, even if Tesla’s intrinsic value dropped to $120 per share, it’s unlikely that you’d lose money since you purchased at $118.47 per share.

(Shortform note: Although investing with a margin of safety has these benefits, experts point out that it also suffers drawbacks. In particular, establishing a margin of safety requires accurately determining a security’s intrinsic value—a practice which, experts warn, rarely lends itself to a precise answer. For example, Buffett’s method of calculating intrinsic value requires estimating a company’s future net income, which is an inherently subjective estimate. For this reason, investors can easily think they’ve established a margin of safety because of a faulty intrinsic value calculation, leaving them overconfident.)

Strategy #5: Use the Expected Value Statistic

Investors use the “expected value” statistic for calculating investment risk, says Charles Wheelan’s book Naked Statistics. To determine the risk of a financial investment, we multiply the financial payoff for each possible outcome by its probability and then add them all together.

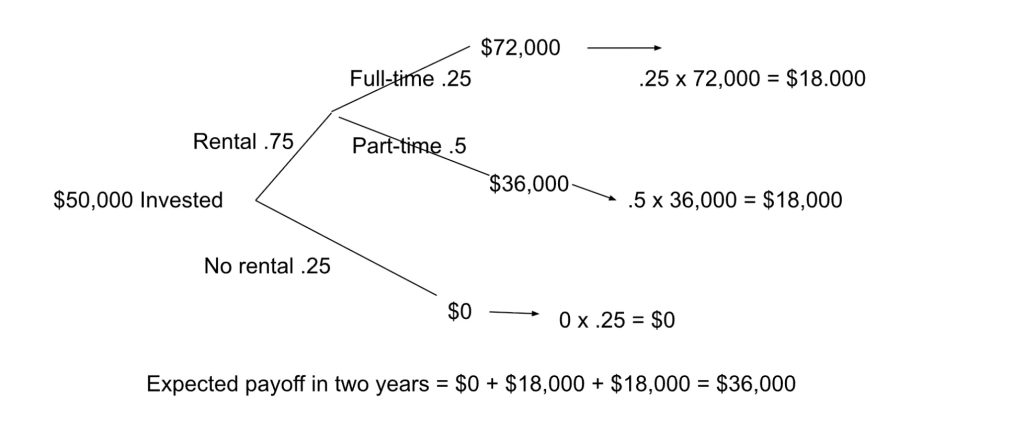

For example, say you were interested in building a tiny house on your property to rent to tourists. It will cost $50,000 to build the house. Based on location and current market demand, you estimate a 25% chance that the house won’t be rented at all during the first two years, a 50% chance that it will be rented “part-time” and earn $1,500/month, and a 25% chance that it will be in high demand and rented “full time,” earning $3,000/month. To calculate the expected value of the investment during your first two years, you would multiply $0 by 25%, $36,000 (for two years of part-time rentals) by 50%, and $72,000 (for two years of full-time rentals) by 25%, and add them together for an expected value of $36,000.

Wheelan explains that we can represent the calculations for the expected payoff visually in a decision tree. For your tiny house, your decision tree would look like this:

Again, probability dictates that your investment is likely worth $36,000 in the first two years. But looking at your decision tree, you can also see that it’s reasonably likely that you’ll make no money at all and also reasonably likely that you’ll only make $18,000.

The decision tree highlights an important lesson in probability: Probability is a tool, not a guarantee. Unless the probability of an event is zero or 100%, we should always be prepared for an unlikely outcome. Wheelan reminds us that statistically improbable things happen all the time (someone’s “illogical” ticket purchase will win them the lottery!).

Since no outcome is guaranteed, Wheelan explains that we all use probability differently depending on our goals, motivation, risk tolerance, and so on. For example, Wheelan points out that the expected value becomes a more and more useful statistic as the number of financial risks one takes increases. Real-estate developers, for instance, can use this tool to make sure that their multiple investments are likely to make money as a whole. Even if one property loses money or underperforms in a given year, as long as the expected value of their portfolio is profitable overall, they are likely to make money.

Decision Trees for Purchasing Stock

As Wheelan explains, probability is an effective tool for managing risk. Unfortunately, many of us underutilize probability when investing in the stock market. Research shows that we tend to overestimate the probability of rare events and our ability to foresee them. For example, people will often invest in a single stock that they think will be the next Apple instead of spreading their investment across a diverse portfolio. This desire to “hit the jackpot” instead of earn a more modest yet statistically likely return on their investment leads people to under-diversify their stock to the detriment of their wallets. Data suggests that these errors in judgment cost the average investor $2,500 per year.

Using a tool to assess the probable outcomes of our financial investments, such as the decision tree described above, is likely a good idea before investing in the stock market. With a decision tree, our “gut feeling” about a stock can be tempered by math, and we may make smarter investments.

More Risk Management Tips by Guatum Baid

In The Joys of Compounding, Gautam Baid offers the following recommendations to learn how to manage financial risk:

Anticipate various outcomes: Actively prepare for both success and failure, even in seemingly stable markets. This proactive stance protects against over-reliance on a particular asset or sector and ensures you’re not caught off-guard by market shifts.

Invest in familiar terrain: Allocate funds to sectors or industries you understand well to diminish the risk of making ill-informed choices based on market hype or misconceptions.

Minimize overhead costs: Be mindful of fees and taxes associated with your investments to ensure they don’t diminish your returns.

Diversify strategically: Distribute your investments across various sectors to shield against substantial losses from a single asset’s underperformance. However, strive for a balanced approach and avoid over-diversifying, as this approach can dilute potential returns.

Demand transparency: Prioritize businesses that favor clear communication in executive correspondence and financial reports. Such clarity often indicates trustworthy management and reduces the risk of unexpected issues or questionable tactics affecting your investments.

Buy low-priced stocks: Purchase assets when their market price is below their estimated value to create a margin of safety. This buffer guards against unforeseen market downturns and helps reduce potential losses.

Discover More About Financial Risk Management

If you want to learn more about the complex psychology behind rewarding children, you can check out the full guides to the books mentioned in this article:

- The Most Important Thing

- Killing Sacred Cows

- Die With Zero

- A Random Walk Down Wall Street

- The Intelligent Investor

- Naked Statistics

- The Joys of Compounding

FAQ

1. What is financial risk?

Financial risk is the possibility of permanent loss and the uncertainty around whether market prices will reflect a security’s true value.

2. Why does knowledge matter when investing?

Financial risk comes from a lack of knowledge, so improving your financial understanding helps you make better, safer decisions.

3. Should I rely on self-insurance?

Self-insurance ties up your money and leaves you exposed to large losses if something unexpected happens.

4. How does Ray Dalio’s risk parity strategy work?

The risk parity strategy involves investing heavily in low-risk assets—sometimes using borrowed money—to achieve more balanced returns.

5. What is defensive investing?

Defensive investing means buying securities below their intrinsic value to create a margin of safety that protects you from loss.

6. What is expected value in investing?

Expected value is a probability-based calculation that estimates the likely payoff of an investment across different outcomes.

7. Why are decision trees useful for financial risk management?

Decision trees help visualize possible outcomes, making it easier to avoid emotional decisions and judge risks more clearly.