PDF Summary:The Great Mental Models Volume 3, by Rhiannon Beaubien and Rosie Leizrowice

Book Summary: Learn the key points in minutes.

Below is a preview of the Shortform book summary of The Great Mental Models Volume 3 by Rhiannon Beaubien and Rosie Leizrowice. Read the full comprehensive summary at Shortform.

1-Page PDF Summary of The Great Mental Models Volume 3

What if you could understand anything in the world by learning a finite set of rules and patterns that apply to all aspects of life? That’s the premise of The Great Mental Models series of books from Farnham Street (FS), a website dedicated to timeless knowledge and insightful ideas.

In this third volume in The Great Mental Models series, FS contributors Rhiannon Beaubien and Rosie Leizrowice borrow models from systems science and mathematics to build a framework for understanding human behavior and viewing the world more objectively. Beaubien and Leizrowice explore topics such as how humans are driven by algorithms, how to earn compound interest on your knowledge and skills, and how not to be fooled by randomness.

In this guide, we organize Volume 3’s models into five broad themes: behavior, group dynamics, efficiency, long-term planning, and statistical thinking. As we explore each theme, we offer suggestions for how to put the book’s models into practice in your daily life.

(continued)...

According to Beaubien and Leizrowice, critical mass is important because it helps you focus your efforts where they’re most needed. If you’re trying to effect change in society—or even in a smaller group—you won’t get very far if you only focus on the moment of change itself because big change is only possible when a system is already critical. By way of analogy, the Civil Rights Act couldn’t have passed in 1954—and it likely couldn’t even have been conceived of in 1864. But even if you’re lobbying for a rules change at work, for example, you’ll probably have more luck if you garner support from your coworkers than if you try to act alone to change things directly.

How to Build Critical Mass

In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell identifies three factors that determine how quickly an idea reaches critical mass. He argues that you can manipulate these factors to spread an idea more quickly and thereby achieve critical mass—and social change—faster. These three factors are:

The fact that some people are more effective at spreading ideas than others. These social superspreaders include people with lots of connections, trusted experts, and people with natural persuasive skills.

How sticky the idea is—in other words, how easy it is to understand and remember, and how well it motivates people to act.

The idea’s context—the environmental and social factors that determine how receptive people are to the new idea. In particular, Gladwell argues that groups of 150 people or fewer adopt new ideas easily because such groups are large enough for peer pressure to influence members’ thinking but small enough for everyone to reach consensus.

Gladwell’s ideas suggest that if you’re working toward social change, you should:

Convince influential people to join your cause early on.

Make your message clear, catchy, and actionable.

Target small groups rather than individuals or large segments of the population.

Where possible, change the environment to make your cause more attractive or easier to act on.

Churn

So far, we’ve been looking at the power of getting more people together and on the same page. But when you’re looking at group dynamics, you also have to think about the rate at which people leave the group. Beaubien and Leizrowice explain that managing churn—the inevitable attrition that happens over time—is key to keeping a group functioning at its best.

The authors explain that churn affects every kind of system. In a physical system such as a car, some parts need to be replaced or replenished regularly (like tires or gasoline) and other parts wear out over time (like the engine or transmission). In a social system, churn is governed by the rate at which new members join a group and the rate at which existing members leave.

In business, churn refers to customer gain vs. retention, and also employee turnover. The authors suggest that in business contexts, rather than trying to eliminate churn—which requires extreme cult-like methods of control and intimidation—you should find the appropriate level of churn that supports optimal growth. Focusing only on attracting new customers and paying no attention to keeping your existing customers limits growth and wastes resources. But focusing only on customer retention at the expense of bringing in new customers also limits growth.

Group Dynamics Influence Each Other

In order to manage churn, you need to consider how it interacts with the other group dynamics we’ve explored. For example, in The Lean Startup, Eric Ries outlines three approaches to growing your customer base. One method is traditional paid advertisements, but the other two depend on group dynamics:

Sticky growth depends on network effects to minimize churn. In sticky growth, a company needs to retain a core set of users so that new users have more incentive to stay—which further increases the incentive for the next batch of new users. This increasing “stickiness” comes from the fact that, as we’ve seen, some products increase in value and usefulness as their user base increases.

Viral growth uses the principles of critical mass to mitigate churn. Viral growth happens when a company gets current customers to recruit new customers through referral incentives (like a reward for each friend who signs up) or automated processes (such as sign-up links automatically included in users’ outgoing emails). If you can get a customer to bring in two other customers (and so on), it doesn’t matter if you then lose that first customer—you’ve still grown overall.

Similarly, the network effect itself requires a critical mass of users for a product or service to be useful. And if you’re trying to enact change by building a critical mass, you need to pay attention to churn—if you’re losing too many supporters, your cause will never take off.

The authors argue that in any social context, churn is necessary for innovation. In academia, for example, new professors bring new theories and new approaches. As their work becomes established and they advance in their careers, they don’t typically move that far from their initial innovations. Instead, the next generation of professors, inspired by and building on (or tearing down) the previous work, are the ones who bring in new ideas and keep the field moving forward.

(Shortform note: When innovation is important, you can intentionally increase churn by imposing term limits. For example, the US military research agency DARPA hires project leaders for only three- to five-year contracts. In doing so, they hope to instill a sense of urgency and to keep new ideas flowing through the organization.)

Part 3: Growth and Efficiency

Now that we’ve seen the kinds of behaviors that emerge as systems grow, let’s look at some models for understanding how systems grow in the first place as well as how and why they break down. The fundamental idea in this section is that systems are nonlinear, which means there’s not always a 1:1 correlation between changes in input and changes in output. Throughout this section, we’ll explain why that is and what you can do about it in order to maximize a system’s efficiency.

Bottlenecks

The authors point out that one of the difficulties in growing a system is that growth inevitably creates bottlenecks, which are the slowest parts of the system. A bottleneck can be:

- A physical limitation or choke point. If you’re preparing a large, complex meal for a crowd, you’ll hit a bottleneck when you run out of burners on your stove.

- An inefficiency in your methods. When you’re preparing the meal, it’s more efficient to gather all of your ingredients before you start cooking. If you keep stopping your prep work to root around in the pantry or the refrigerator, that behavior creates a bottleneck.

- A resource shortage. If you run out of onions, you won’t be able to prepare any more tomato sauce until you buy more, meaning there’s a bottleneck on your sauce output.

In each of these cases, the bottleneck serves as a limiting factor—it either slows the system down or it limits how much output the system can create.

The Importance of Identifying Bottlenecks

Not only do bottlenecks slow systems down, but they can also lead to more problems if we don’t identify them properly. In Thinking In Systems, Donella H. Meadows points out that when we misidentify a bottleneck, we often try to solve the problem by adding more input, which only creates backlogs and waste. For example, if you’ve run out of burners on the stove, you won’t get the meal cooked any faster by continuing to pile ingredients on the counter—in fact, the added clutter will only get in your way. And left long enough, the backlogged ingredients will start to spoil before you can get to them.

Similarly, companies and governments can easily waste money and resources by pouring them into systems that are suffering from undiagnosed bottlenecks. For example, in Basic Economics, Thomas Sowell argues that foreign aid typically fails at its intended purpose (improving life in poor countries) because in many cases the fundamental problem isn’t a lack of money—it’s corrupt leadership, a lack of a skilled and educated workforce, and so on.

Beaubien and Leizrowice point out that addressing bottlenecks is an ongoing process because removing one bottleneck always reveals another. In other words, when you fix a bottleneck, the system starts growing again until its increased size reveals another bottleneck somewhere else. In the above example, if you had access to more burners, you’d be able to get more components cooking at once. But eventually you’d hit another bottleneck when you exceeded your capacity to keep up with all the stirring, flipping, and combining on your own. If you recruited some friends to help you in the kitchen, you’d remove that bottleneck, but only until there were too many people to work effectively in a small space.

(Shortform note: In practice, this principle means that no system can grow forever. For that reason, in Thinking In Systems, Donella H. Meadows suggests deciding which limits you can live with and making your peace with them. Doing so can also open the door to alternative ways to solve a problem. In our cooking example, unless your goal is to run a commercial kitchen, your best bet is to figure out how many people you can comfortably cook for at once and plan your dinner parties accordingly. That could mean inviting fewer guests, but it could also mean buying prepared food or hosting a potluck—both of which would reduce your cooking load.)

Because there will always be a bottleneck somewhere in the system, the authors suggest that you plan ahead and address fundamental causes that will eliminate as many bottlenecks as possible down the line. Though you can never completely eliminate bottlenecks, you can make your life easier by thinking of potential problems in advance instead of reacting to them as they arise.

Diagnosing Bottlenecks With the Five Whys

One way to plan for future bottlenecks is by using what entrepreneur Eric Ries calls the Five Whys. In The Lean Startup, Ries argues that when you encounter a problem, asking “why?” five times in a row helps get to the root causes of the problem. For example:

Why wasn’t there enough pasta sauce at the dinner party? We ran out of onions.

Why did we run out of onions? We didn’t buy enough onions.

Why didn’t we buy enough onions? We didn’t know how many we needed.

Why didn’t we know how many we needed? We didn’t know how much sauce we needed.

Why didn’t we know how much sauce we needed? We didn’t know how many people were coming to dinner.

If we stopped with the first why, we might conclude that we could avoid future problems by filling the pantry with onions. But by going through the Five Whys, we discover that we can avoid running out of onions—and any other ingredient, not to mention place settings, table space, and so on—by asking guests to RSVP.

Diminishing Returns

When you run into a bottleneck, you’ll discover that adding more input doesn’t always increase output—a phenomenon known as diminishing returns. Beaubien and Leizrowice say that the model of diminishing returns describes any situation in which input increases output only up to a point: Past that point, more input has less and less effect.

For example, if you’re trying to learn about a new subject, the first few books you read will probably have a big impact on your knowledge. As you read more books, you’ll keep learning more, but not as much or as quickly as you did at first, because now you already have a base of knowledge. Eventually you’ll reach a point where you know the field well, and each new book might only add a nuance here or there. (Shortform note: Sometimes, diminishing returns result from bottlenecks—as we saw earlier, it does little good to keep adding input to a bottlenecked system.)

The idea of diminishing returns also applies to cases where small amounts of input have a disproportionately large influence on the output. The authors cite the Pareto principle, which states that about 20% of a system’s input is more influential than all the rest, as that 20% generates about 80% of the system’s output. In the example of learning about a new subject, the first 20% of your reading might develop 80% of your knowledge base. That means that adding more knowledge takes disproportionate amounts of time and effort. Unless your goal is to become a world expert on that topic, your time and energy might better be spent elsewhere.

(Shortform note: In The One Thing, real estate entrepreneur Gary Keller suggests using the 80/20 rule to boil a large goal down into a single essential action. To do so, he says, once you’ve identified the 20%, find the 20% of that 20% and so on until you hit the “one thing” that will make a bigger difference to your goal than anything else you could do.)

In some cases, this disproportionate influence happens because the system adapts to the input. The authors cite the example of horror movies, which are constantly one-upping each other in terms of graphic violence and other scare tactics. But movie maniacs can only wield so many machetes and chainsaws before audiences get jaded and what started out as shocking becomes trite.

(Shortform note: This form of diminishing returns is also known as hedonic adaptation: When something good or bad happens to us, it affects our happiness for a while, but then the novelty wears off and we return to a baseline level of happiness. Similarly, the more you do something pleasurable, like eating a favorite food, the less that activity increases your happiness. To avoid hedonic adaptation, you can rotate through different things you enjoy or use techniques like gratitude journaling to increase your appreciation for your positive experiences.)

Part 4: Long-Term Thinking

As we’ve seen, if you’re looking to maintain or grow a system, it pays to plan ahead. To help you do so, this section focuses on several models that encourage effective long-term thinking. The central theme of this section is that being open-minded and broadening your knowledge can lead to big gains down the road. These gains might be material or they might come in the form of enhanced creativity or greater preparedness for the unknown.

Compounding

One major reason to think long term is that doing so lets you capitalize on the effects of compounding. The authors explain that investments of money, knowledge, and effort compound over time, leading to exponential (rather than linear) gains.

The model of compounding comes from finance and economics, where it refers to compound interest—the process of adding interest earnings back to an initial investment in order to earn more interest next time. If you put $100 in an account with a 10% daily interest rate, the next day your account will have $110—you earned $10 in interest. If you leave that money alone, then on the third day you’ll have $121—this time, you earned $11 in interest.

Beaubien and Leizrowice argue that a similar form of compounding happens as you build knowledge and skills over time. For example, if you’re just learning to cook, making dinner takes a long time—your knife work is slow, you measure everything carefully, and you keep checking the recipe to see what to do next. But eventually, the physical skills become second nature and you begin to internalize the basic principles and techniques that dishes are based on. Your cooking becomes a lot faster because new recipes aren’t really new—they’re variations on things you already know how to make. Moreover, you can take on more complicated dishes than you could at first because you’ve built an ever-increasing base of knowledge and skill.

(Shortform note: In Atomic Habits, James Clear takes the idea of compounding even further by arguing that your identity is the product of your actions—in other words, that your behaviors compound over time to produce who you are as a person. The good news, from this point of view, is that you can capitalize on this compounding by using small changes to create major transformations in your life.)

Surface Area

Even when it’s happening, sometimes compounding isn’t obvious because there’s no way to know what gains await you down the line. For this reason, the authors recommend that you increase your surface area by exposing yourself to as many new ideas and experiences as possible. They point out that in geometry and physics, the more surface area an object has, the more (literal) connections it has to the world around it—and the more connections, the more opportunities to exchange molecules, energy, and so on.

By way of analogy, the greater your surface area, the more connections you make and the greater your chances to find unexpected opportunities and new applications for things you’ve learned before. Building on the last example, when you learn to cook, you learn more than just how to prepare food. You learn how to organize, prioritize, problem solve, and manage your time. These skills will come in handy for years to come in your job, hobbies, and daily life.

(Shortform note: In other words, increasing your surface area builds your collection of what educators and career experts call transferable skills—abilities and knowledge that you learn in one context but can apply in many other contexts as well. The more transferable skills you have, the more challenges you’ll be able to face. And the more aware you are of your transferable skills, the more competitive you’ll be when looking for jobs or other opportunities.)

So how do you increase your surface area? The authors recommend being curious and open to new things. They also recommend cultivating your relationships, pointing out that networking is another form of compounding because each person you know exponentially increases your chances of meeting another new person or finding a new opportunity.

(Shortform note: Growing your skills and knowledge can help you grow your relationships, and vice versa: If you’re at a party, your cooking experience might help you strike up a conversation about the food with another guest. And as with skills and knowledge, you never know where your personal connections will lead you or when. Maybe your fellow partygoer—who happens to be a professional chef—is impressed with your insight into the food and invites you to interview for a job at her restaurant.)

Part 5: Looking at the Big Picture

As you work through any of the models we’ve discussed so far, you’ll stand the best chance of success if you have an accurate view of the world. Unfortunately, because each of us has a limited perspective, sometimes it’s hard to see the big picture—and easy to misinterpret some situations as a result. This final section introduces several models drawn from mathematics that can help us see the big picture more clearly. The basic theme of this section is that by thinking statistically, you’ll have a clearer context for the things you encounter.

Distributions

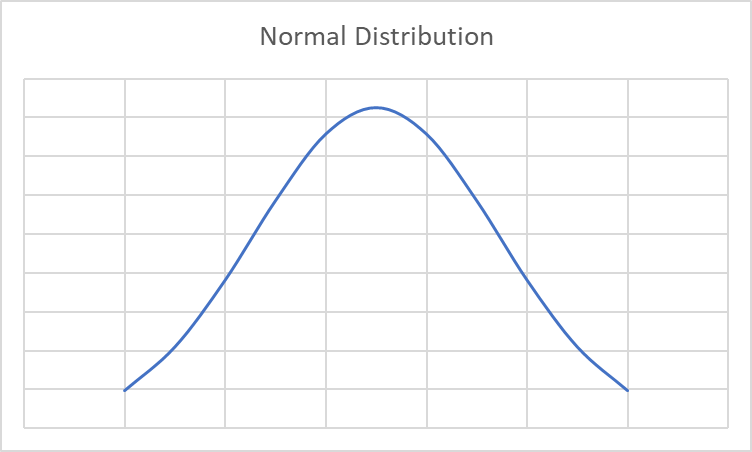

Beaubien and Leizrowice argue that in order to have accurate contexts for information, you need to understand probability distributions. In statistics, a distribution describes how likely different results are in a given data set. The best known distribution is probably the bell curve—in technical terms, it’s called a normal distribution.

In a normal distribution, most of the values are somewhere near the middle with values becoming less common the more they deviate from the average. Often, student grades work this way, with Cs being more common than Bs or Ds, which are more common than As or Fs. (Shortform note: We tend to think that the more average something is, the more common it is. That’s true in the normal distribution, but it’s not always true in life. As we’ll see in a moment, equating averageness with commonness can lead to serious misconceptions of real-world situations.)

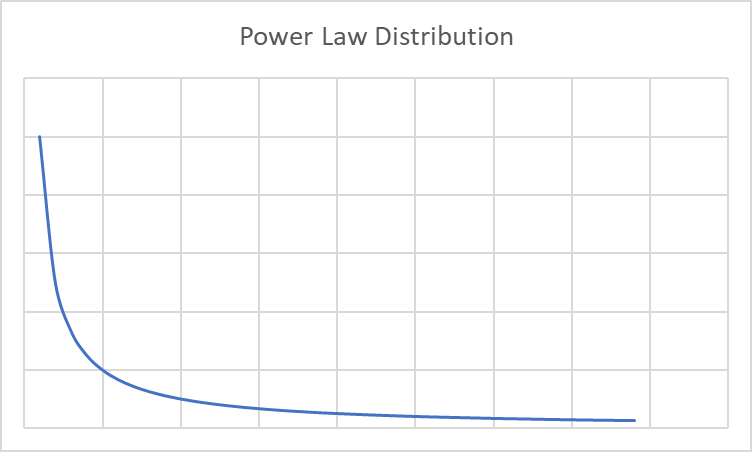

While the normal distribution is familiar and widespread, Beaubien and Leizrowice point out that many important phenomena follow other distributions, such as the power law distribution.

Power law distributions describe situations where most items cluster around either a high or low point on the scale rather than clustering around the middle. The further from the high or low point, the less likely a value is. For example, most of us aren’t especially fast sprinters. If the chart above measures 100 meter dash times, with better times on the right side of the chart, most people will be near the left—that’s why the curve is highest there. As you move from left to right, you’ll find fewer people (high school athletes), then fewer still (college athletes), then fewer still (Olympic athletes), until at the far end you find Usain Bolt.

The Importance of Understanding Distributions

A major takeaway from this discussion of distributions is that you always need to look for the greater context for information, especially when you’re dealing with figures and statistics. You also need to remember that our intuitive notions about things like averages can sometimes lead us astray.

For example, Beaubien and Leizrowice point out that wealth follows a power law distribution, with most of the world’s wealth concentrated among a few people while most people have exponentially fewer resources—in fact, recent studies show that .01% of the world’s population owns 11% of its wealth and that gaps in income and wealth have only widened over the past decade.

If we want to address problems like wealth inequality, we first need to see them clearly. But if we don’t have a clear understanding of distributions, it’s easy to misinterpret the situation in a way that masks the problem.

Take the idea of average income. In a normal distribution, average values tend to be more widespread. But that’s not true in a power law distribution. For example, imagine there are 10 people in a room. Nine of them make $30,000 per year. The 10th person makes $2,000,000 per year. The average income among these 10 people is $227,000.

Obviously, that doesn’t tell us anything—none of the 10 people in the room make anywhere near that figure. But if all we knew was the average income, we might conclude that everyone in the room was quite wealthy (an individual annual income of $227,000 would put you in the top 3% of Americans in 2021). In other words, by not recognizing which distribution curve is at work, we might completely miss the income inequality among those 10 people.

Randomness

Whereas distributions can help you understand the patterns behind facts or events, the model of randomness can help prevent thinking errors by reminding you that sometimes there isn’t a pattern to be found. Beaubien and Leizrowice argue that most of what happens does so by chance. They say that we don’t realize this because humans constantly try to connect events into stories with clear cause-effect relationships.

(Shortform note: This is known as the narrative fallacy. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman explains that the narrative fallacy occurs because we tend to look for patterns and causal explanations even where none exist. For example, he says that during the German bombing of London during World War II, people suspected that there were German spies housed in unbombed areas of the city—so much was bombed that people assumed the untouched areas must have been left alone for a reason. In fact, Kahneman says, the distribution of bombed and unbombed areas was totally random.)

The idea that the universe is mostly random might seem scary at first, but Beaubien and Leizrowice point out that recognizing randomness has numerous benefits, starting with better decision-making. For example, if you keep in mind that your observations are subject to randomness, you’ll realize that it’s important to have a sufficient number of observations before you draw any conclusions. In the example of wealth distribution above, if you only consider two of the 10 people in the room, you’ll have a totally inaccurate picture of the situation—you might conclude either that everyone in the room makes $30,000 or that half of them make $30,000 and half of them make $2,000,000.

(Shortform note: In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman argues that this is another way that narrative thinking leads to mistakes: Because we’re quick to make causal links between facts, we can forget to make sure we have a big enough sample to support the conclusion we’ve drawn.)

Understanding randomness also helps you avoid making faulty predictions. The authors point out that a fair coin is equally likely to land on heads or tails on any given flip. That means that even if it comes up heads 10 times in a row, it still has a 50% chance of coming up heads the next time. It can be easy to forget that, because we intuitively realize that the odds of flipping heads 10 times in a row are extremely low—1 in 1,024 to be exact. Therefore, when we see 10 heads in a row, we might think the coin is due to come up tails. This mistake is called the gambler’s fallacy—and casinos make big profits off it all the time.

(Shortform note: The gambler’s fallacy is yet another example of our tendency to look for patterns. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman points out that the coin flip pattern HTHTTH “looks more random” than HHHTTT or TTTTTT—yet each of these sequences is equally likely when you flip a coin six times. He adds that because the other two patterns look less random, we have more of a desire to understand—and create—a “why” for their occurrence.)

Regression to the Mean

Another lesson we can learn from randomness is that the past doesn’t always predict the future. According to Beaubien and Leizrowice, the principle of regression to the mean suggests that unusual results are most likely to be followed by ordinary results rather than by additional unusual results. For example, in 2021, the average SAT score was 1060. If you randomly sampled 10 test takers from that year and found that those 10 students averaged 1500, it’s most likely that a second random sample of 10 will average much closer to 1060 than 1500.

The reason to keep regression to the mean in mind is that it’s easy to look at a result and construct stories with no basis in reality. For example, if an athlete has a great rookie season followed by a mediocre career, announcers might say that she let early success go to her head, or that the league figured her out, or that she burned out early. In reality, she might simply have had an unusually lucky season followed by years of solid performance at her true skill level. If that’s the case, her apparent dropoff in performance was entirely random.

(Shortform note: Moreover, our tendency to look for correlations among randomness can also lead to faulty understandings of our own behavior. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman points out that it often wrongly appears that punishment leads to improved performance when in fact, the initial poor performance that led to the punishment was a random outlier, and the subsequent “improved” performance would have happened anyway. But if we just notice that punishment is followed by improvement, we might adopt an unnecessarily punitive management style based on this misconception.)

Randomness and Creativity

One final reason Beaubien and Leizrowice say we should embrace randomness is that randomness is at the heart of creativity. We’ve already talked about the fact that we never know where our investments of time and learning will lead us. That’s especially true when it comes to creative activities. The authors point out that novelists often can’t explain where they get their ideas because so much creative inspiration is the result of random chance and the unexpected combinations of prior experience and knowledge. (Shortform note: In fact, there are numerous tools that harness randomness to spark creativity. These tools range from dice based story generators to cards with cryptic instructions designed to help in music production to websites that give random prompts for visual artists.)

Want to learn the rest of The Great Mental Models Volume 3 in 21 minutes?

Unlock the full book summary of The Great Mental Models Volume 3 by signing up for Shortform.

Shortform summaries help you learn 10x faster by:

- Being 100% comprehensive: you learn the most important points in the book

- Cutting out the fluff: you don't spend your time wondering what the author's point is.

- Interactive exercises: apply the book's ideas to your own life with our educators' guidance.

Here's a preview of the rest of Shortform's The Great Mental Models Volume 3 PDF summary:

What Our Readers Say

This is the best summary of The Great Mental Models Volume 3 I've ever read. I learned all the main points in just 20 minutes.

Learn more about our summaries →Why are Shortform Summaries the Best?

We're the most efficient way to learn the most useful ideas from a book.

Cuts Out the Fluff

Ever feel a book rambles on, giving anecdotes that aren't useful? Often get frustrated by an author who doesn't get to the point?

We cut out the fluff, keeping only the most useful examples and ideas. We also re-organize books for clarity, putting the most important principles first, so you can learn faster.

Always Comprehensive

Other summaries give you just a highlight of some of the ideas in a book. We find these too vague to be satisfying.

At Shortform, we want to cover every point worth knowing in the book. Learn nuances, key examples, and critical details on how to apply the ideas.

3 Different Levels of Detail

You want different levels of detail at different times. That's why every book is summarized in three lengths:

1) Paragraph to get the gist

2) 1-page summary, to get the main takeaways

3) Full comprehensive summary and analysis, containing every useful point and example