Imagine thinking you’ve figured out how the universe works—only to discover everything operates by rules that seem to defy common sense. That’s exactly what happened to physicists in the early 1900s when they started studying atoms and light.

Classical physics treated the world like a predictable machine. But experiments shattered assumptions, forcing scientists to build an entirely new framework: quantum mechanics. Keep reading to explore the difference between classical physics and quantum mechanics and learn how the revolution revealed a reality far stranger than anyone imagined.

Table of Contents

The Difference Between Classical and Quantum Mechanics

In his book What Is Real?, Adam Becker explains that, at the dawn of the 20th century, physicists believed they had mapped reality’s basic structure. But experiments with atoms shattered their most fundamental assumptions about the world. Becker reports that this forced physicists to develop an entirely new branch of physics—and a new mathematics to describe it. It revealed that nature’s building blocks operate according to rules so strange they seem to violate logic. Let’s examine what physicists thought they knew about the world and how quantum mechanics overturned those ideas.

What Physicists Thought They Knew

Becker explains that classical physics rested on intuitive assumptions about reality that successfully explained the observable world. Physicists viewed atoms as the fundamental building blocks of matter—tiny spheres that combined to create chemical compounds. In their view, each atom had a specific position, velocity, and energy that only changed according to Newton’s laws. Later discoveries revealed that atoms aren’t actually solid spheres but consist mostly of empty space, with electrons orbiting a dense nucleus containing positively charged protons. This “planetary model” suggested that atoms functioned like miniature solar systems, obeying the same physical laws as planets and stars.

(Shortform note: The progress in our understanding of the atom illustrates what scientists mean by a “theory,” an explanation for observations that brings together many facts and hypotheses, and can be changed or abandoned as it’s tested against new evidence. We can see this progression in atomic theory: The Ancient Greeks imagined atoms as indivisible particles. John Dalton pictured them as solid balls of different weights that combined to make compounds. J.J. Thomson’s “plum pudding” model envisioned them as balls of positive matter with negative electrons scattered throughout, like raisins in pudding. Then, Ernest Rutherford’s experiments showed that atoms consist of a nucleus surrounded by electrons, hence the planetary model.)

The planetary model of atoms wasn’t the only assumption classical physics took for granted. Physicists believed energy flowed continuously, like water from a faucet—you could have any amount of energy, from a lot to a little to any fraction in between. They distinguished between waves and particles: Waves spread out through space and interfered with each other when they met, while particles followed definite paths and collided like solid objects. Finally, physicists assumed all objects had definite properties, whether you observed them or not.

| The Assumptions Behind Modern Physics Even today, physics rests on fundamental beliefs about the universe, while acknowledging that prior assumptions—such as those Becker lists—have been overturned. As Neil deGrasse Tyson explains in Astrophysics for People in a Hurry, modern science assumes that physical laws remain constant across space and time, so the same rules that govern atoms here on Earth also govern stars billions of light-years away. This assumption of universality allows physicists to make meaningful predictions about distant objects and past events. But Tyson points out that building science atop assumptions also requires accepting that all scientific knowledge is provisional and subject to change as new evidence emerges. For example, Newton’s laws seemed to work perfectly for centuries—until Einstein showed they were built on unfounded assumptions that caused them to break down at extreme speeds and masses. Even Einstein’s theories might someday need revision. This reveals something uncomfortable about science: Successful theories aren’t discoveries of absolute truth, just our best current descriptions of the patterns we observe. When we say “energy flows continuously,” we can’t claim to have discovered energy’s true essence: We’re describing how energy appears to behave. Our theories organize and predict our experiences, but they remain human constructs rather than direct glimpses of reality. |

What Quantum Mechanics Reveals Instead

At the time, physics stood on the precipice of a paradigm shift: Becker explains that experiments with atoms and light revealed a microscopic world where energy comes in discrete chunks rather than flowing smoothly, where matter and light exhibit properties of both waves and particles simultaneously, and where electrons can occupy only specific energy levels rather than any arbitrary energy value. When physicists developed new mathematics to explain these observations, they discovered that particles can exist in multiple states at once and influence each other across vast distances—phenomena that seem to contradict everyday experience.

(Shortform note: Becker describes quantum mechanics as representing a “paradigm shift,” a term coined by Thomas Kuhn to explain how science progresses. A “paradigm” is a framework of assumptions, methods, and values that guide how scientists approach problems. Kuhn wrote in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that “normal science” happens as researchers accumulate facts and solve puzzles within an established paradigm. But when they find too many anomalies that the current paradigm can’t explain, they have to adopt a new paradigm to better explain their observations. Kuhn showed that scientific “progress” isn’t always linear: Sometimes, moving forward requires abandoning what we thought we knew.)

Energy Comes in Packets Called “Quanta”

Becker reports that the first assumption of classical physics to fall was that of energy’s continuity. In 1900, German physicist Max Planck tackled a practical problem: improving lightbulbs by studying how heated objects emit light. Everyone knew the pattern: A poker left in a fireplace starts black, then glows red, then orange, then white-hot. Classical physics predicted that heated objects should emit all colors of light equally, which would make the light look white at any temperature. Planck discovered he could explain real-world observations only by abandoning the continuity assumption and replacing it with a new one: Energy comes in indivisible packets, which Planck called “quanta,” like coins that can’t be broken into smaller denominations.

According to Becker, Planck’s key insight was that different colors of light require different-sized energy packets. Higher-frequency light (like blue) demands larger energy packets than lower-frequency light (like red). This explained the poker’s color progression: At low temperatures, heated objects lack the energy to create the large packets that higher-frequency colors require, so they emit red and orange light. As temperature increases, more energy becomes available, shifting the glow toward white. Albert Einstein extended this insight in 1905, proving that light itself travels in discrete, quantized packets called “photons.”

| The Pixelated Universe: What “Quantized” Really Means What does it actually mean for energy to be “quantized”? Think of your smartphone screen: From a distance, images look smooth, but zoom in far enough and you’ll see the pixels that make up the picture. Quantum physics suggests energy works the same way. Light, which is a form of energy, can only come in whole photons—you can’t have half a photon, just as you can’t have half a pixel. Imagine a video game character casting a spell: The light streaming from their wand is made of individual pixels on your screen, each one either on or off, never half-lit. In the real world, light works similarly. Atoms can only emit whole photons, which is why heated objects glow in specific color patterns rather than in every possible shade. But, if energy and light are essentially pixelated, some scientists wonder: What if space and time are also made of pixels? That would mean there’s a smallest possible distance between any two particles, just as video game characters only occupy specific positions, and a smallest unit of time. Objects couldn’t exist closer together than one “space pixel” apart, and events couldn’t occur closer together in time than one “time pixel.” These pixels would be millions of times smaller than atoms, but scientists are running experiments to find out if they exist. |

Matter and Light Behave Like Both Waves and Particles

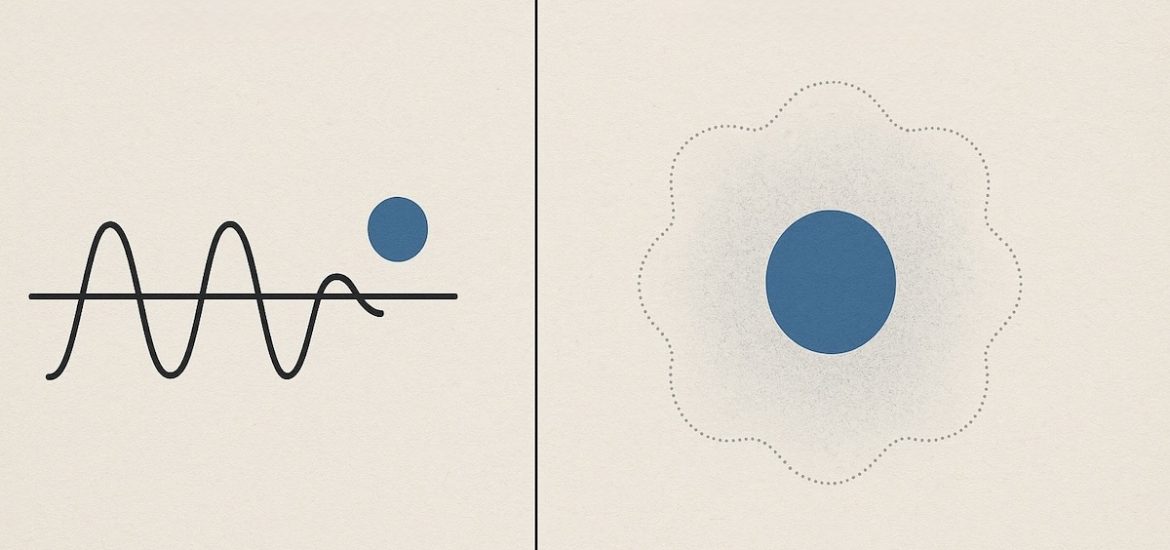

Next to fall was the classical distinction between waves and particles. Physicists discovered that light and matter exhibit wave and particle properties at the same time, depending on how you observe them. Becker explains how the double-slit experiment demonstrates this: When physicists fire individual electrons toward a barrier with two parallel slits, classical physics predicts the electrons should behave like tiny particles, passing through one slit or the other and creating two distinct bands on a detection screen. Instead, something seemingly impossible happens: The electrons create interference patterns—alternating bright and dark bands shaped like patterns created by waves when they overlap, such as those in a pond.

The only explanation is that each electron somehow travels through both slits simultaneously and interferes with itself on the other side. But, as Becker notes, the mystery deepens: If physicists place detectors at the slits to track which path each electron takes, this makes the wave pattern vanish. The electrons behave like ordinary particles, each traveling through exactly one slit. The act of observation changes the electron’s behavior from wavelike to particle-like, showing that the universe’s basic building blocks are neither waves nor particles, but something that exhibits aspects of both categories.

| What Does Wave-Particle Duality—and Quantum Probability—Actually Mean? The double-slit experiment reveals why quantum mechanics must rely on probability—the mathematical likelihood that a particular outcome will occur. When we fire electrons at two slits, we can predict exactly what the overall interference pattern will look like, but we can’t predict where any individual electron will land. This is a departure from classical physics, where knowing a system’s initial conditions theoretically lets you predict its exact behavior. So why does quantum mechanics require probability? There are three very different possibilities. First, we can see probability as a result of our ignorance: Maybe each electron travels through one slit, following a path we can’t track, so probability reflects our incomplete knowledge. Second, probability could reflect that nature is random: Maybe the electron travels through both slits until measurement forces it to randomly “choose.” Third, probability could be necessary if there are multiple realities: Maybe both outcomes occur, but in separate universes, and probability represents which one you’ll find yourself in. As we’ll see, the answer to this question is key to the debate over what quantum mechanics says about reality. |

Particles Can Occupy Only Specific Energy States

Classical physics predicted that electrons should orbit nuclei like planets around the sun, occupying any possible orbit and gradually spiraling inward while radiating energy. This energy would be detectable as a continuous rainbow of colors as electrons move through all possible positions. But Becker explains that, when physicists heated different elements to examine the light they produced, they discovered something unexpected: Each element produces only specific colors with sharp boundaries between them. Sodium always produces yellow light, hydrogen emits distinct wavelengths of red, and every other element has its own unique colors.

Danish physicist Niels Bohr solved this puzzle in 1913 by proposing that electrons can only occupy specific energy levels around atomic nuclei—like a staircase where electrons can stand on particular steps but never in the spaces between. When electrons jump between levels, they emit or absorb light with energy precisely equal to the step difference, explaining why each element produces characteristic colors. As Becker explains, this principle applies universally: Vibrating molecules, spinning nuclei, and all atomic-scale systems exist only in discrete states determined by quantum mathematics. The smooth, continuous world of classical physics was thus completely overthrown at the microscopic level.

| Why Electrons Can’t Just Go Anywhere: The Standing Wave Solution Why can’t electrons exist between the steps of Bohr’s staircase? The answer requires a shift in thinking: Electrons aren’t tiny particles, but “standing waves” that must fit perfectly within the atom. Standing waves are patterns that vibrate in place rather than traveling. Think of a guitar string: When you pluck it, only certain wavelengths can form stable vibrations that fit the string’s length. If a wave doesn’t fit, it cancels itself out through interference. Electrons work the same way, except the electron itself is the wave pattern. Just as only certain waves can exist on a guitar string, only certain electron “waves” can exist around an atomic nucleus. Each stable pattern corresponds to an energy level. So when an electron “drops” from a higher energy level to a lower one, the electron wave pattern rearranges itself from one stable shape to another. When this happens, the energy difference is released as a photon. Understanding electrons as waves isn’t just a convenient mathematical description: Particle physicist Matt Strassler (Waves in an Impossible Sea) explains that electrons actually are waves. This might seem to contradict wave-particle duality, but Strassler suggests we should think of electrons as “wavicles”: They’re fundamentally wave-like (spread out, vibrating) but come in indivisible units, which is what makes them seem particle-like. |

Mathematics Revealed Superposition and Entanglement

These experimental discoveries demanded entirely new mathematical tools. Becker writes that, from 1925 to 1926, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger independently developed frameworks to describe quantum reality. Heisenberg’s “matrix mechanics” used abstract number arrays where normal arithmetic rules failed, while Schrödinger’s “wave mechanics” treated particles as waves governed by precise equations. Connecting these approaches showed that wave functions represent the probabilities of particles appearing in different states, meaning quantum mechanics could only predict likelihoods, never definite outcomes.

| Two Ways to Describe the Same Reality These approaches describe the same reality in two different ways. Heisenberg used matrices: tables of numbers that represent properties such as a particle’s position or momentum. In regular math, 3 x 2 equals 2 x 3, but in quantum matrices, changing the order of multiplication changes the results. Meanwhile, Schrödinger used functions: formulas that give one output for each input. With Schrödinger’s wave functions, you can input any location and get the probability of finding the particle there. These probabilities spread through space like waves, where peaks indicate locations where the particle is more likely to be found. For decades, physicists assumed these two approaches were mathematically equivalent. But recent analysis suggests they might actually use different rules for connecting quantum math to classical physics, revealing unresolved complexities. |

Once Heisenberg and Schrödinger developed the math, things got even stranger. Becker explains that the mathematics revealed quantum reality’s most bizarre features: superposition and entanglement. Superposition means particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously. Entanglement creates connections between particles so that measuring one immediately affects its partner, regardless of how far apart they are, violating the rule that nothing travels faster than the speed of light. Nevertheless, Becker notes that Heisenberg and Schrödinger’s math could predict experimental results perfectly. This created a crisis: If the math works so well, what does it tell us about the nature of reality?

(Shortform note: Superposition and entanglement are more connected than they first appear; research shows these quantum behaviors always go together. Here’s why: Entanglement is essentially superposition involving multiple particles. When particles become entangled, the entire system exists in a superposition of different combined states, like two coins that are somehow both “heads-heads” and “tails-tails” at the same time until someone looks. You can think of entangled particles as twins who share the same fate no matter how far apart they are. This connection is so fundamental that any theory allowing particles to exist in multiple states simultaneously will automatically create these correlations between separated particles.)

Learn More About Classical and Quantum Physics

To better understand the transition from classical physics to quantum mechanics, check out Shortform’s guide to the book What Is Real? by Adam Becker.