Image credit: PR Image Factory/shutterstock.com

Do you wake up each morning with a clear sense of purpose, or do you struggle to find the motivation to pursue your goals? The ancient Japanese concept of ikigai offers a powerful solution to the motivation crisis that leaves many people feeling stuck and unfulfilled.

This comprehensive guide explores how finding your ikigai can transform your approach to goal-setting and life satisfaction. Drawing from Anthony Raymond’s Ikigai & Kaizen and Héctor García and Francesc Miralles’ Ikigai, you’ll discover why external rewards often diminish motivation while internal rewards create lasting drive, along with practical exercises to help you identify your unique ikigai.

Table of Contents

Why Find Your Ikigai?

In his book Ikigai & Kaizen, Anthony Raymond argues that one reason people struggle to pursue goals is that they lack the right motivation. We’ll explore this obstacle in greater depth before turning to the solution Raymond proposes: finding your ikigai.

Obstacle: You Lack Motivation

Raymond explains that you set a goal for one of two reasons:

- You believe achieving it will allow you to acquire external rewards such as social approval or money.

- You believe pursuing it will allow you to experience internal rewards such as enjoyment or satisfaction.

He suggests that you’re more likely to feel unmotivated when you’re too focused on external rewards.

Why External Rewards Decrease Motivation

According to Raymond, goals motivated only by external rewards are difficult to act on because they don’t align with what fulfills you, nor do they provide opportunities to spend time on your interests. As a result, they don’t inspire positive emotions that make you want to work toward your goal. Instead, you focus only on the potential result of achieving your goal (the external reward), and you perceive goal-related tasks as chores that you should do to make it to the finish line. According to Raymond, this perception makes it difficult to summon the energy to take action and make meaningful progress.

Over time, your lack of progress makes you associate goal-related tasks with uncomfortable feelings that make it increasingly difficult to take action: Each time you think you should work on your goal, your lack of enjoyment heightens your awareness of other things you’d rather be doing. This awareness causes you to resent spending time on goal-related tasks, making you prone to procrastination. Then, giving in to procrastination sparks feelings such as guilt (for not progressing) and anxiety (because there’s so much left to do)—leaving you too emotionally drained to take action.

Why Internal Rewards Increase Motivation

On the other hand, Raymond argues that goals motivated by internal rewards are easier to act on because you associate the process of working toward them with pleasurable feelings. This is because such goals align with what fulfills you—meaning, you choose to pursue these goals because they enable you to spend time on interests that inspire positive emotions.

As a result, you enjoy working on goal-related tasks, and your enjoyment creates a positive feedback loop that reinforces your desire to take action: Each time you work toward your goal, your positive emotions make you want to immerse yourself in goal-related tasks. The more you immerse yourself, the easier you find it to develop the confidence and abilities you need to overcome challenges and make progress. This progress invigorates you and makes you want to keep taking action.

Solution: Find Your Ikigai

In their book Ikigai, Héctor García and Francesc Miralles explain that you can think of your ikigai as your “existential fuel.” It’s the thing that keeps you going in life and the reason you get up in the morning. Your ikigai could involve helping people or enjoying their companionship. It could involve an art or craft, such as writing or painting. It could involve a sport or activity. It could involve business, science, or any number of other things.

You don’t necessarily have just a single ikigai. Einstein, for example, had two ikigais: physics and playing the violin. He said that if he hadn’t been a physicist, he would have devoted his life to music.

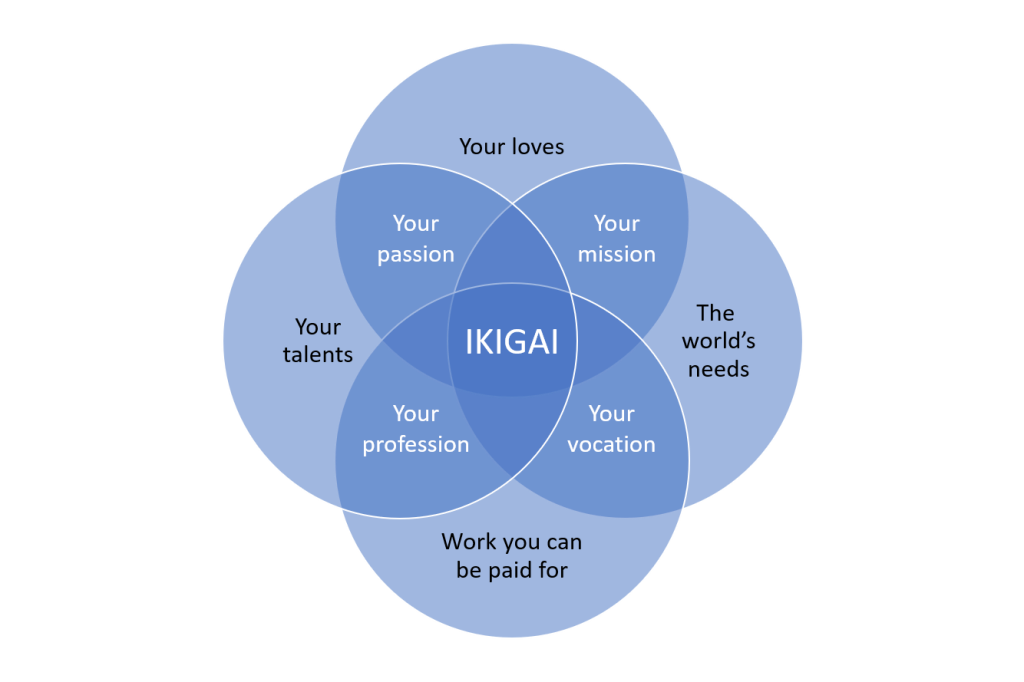

The following diagram helps to illustrate the various elements that go into your ikigai.

Anthony Raymond argues that knowing your ikigai boosts motivation by helping you set goals that promise internal rewards. Similar to García and Miralles, Raymond says that ikigai is a concept that roughly translates to “your reason for being,” referring to the personal and professional activities that give your life a sense of meaning or purpose.

He says that an ikigai combines four elements that naturally generate internal rewards:

1. It’s something you love doing. This makes working on goal-related tasks pleasurable and satisfying. (Shortform note: According to research in the area of positive psychology, focusing on what you love also improves your chances of achieving your goals. Because these goals allow you to experience an upward emotional spiral (increased feelings of happiness and satisfaction), you’re able to access the best parts of yourself—your unique strengths and talents—and apply them to successfully achieve your goal.)

2. It’s something you’re good at, or are willing to become good at. This ensures your actions lead to positive results. Each small win boosts your confidence in your ability to make progress. (Shortform note: In addition to boosting confidence, being competent drives progress by increasing concentration. Kotler (The Art of Impossible) explains that being good at a task increases your chances of completing it successfully. Each time you complete a task, you trigger a dopamine spike that increases your motivation and concentration, making you want to tackle increasingly challenging tasks. It follows that being good at what you do creates a positive neurochemical feedback loop that makes it both easy and pleasurable to gain momentum toward achieving your goal.)

3. It’s something that benefits others. This aligns goal-related tasks with a larger purpose, making them feel meaningful and fulfilling. (Shortform note: Daniel H. Pink (Drive) clarifies why aligning your goal with a larger purpose increases your motivation: You’re biologically wired to want to help other people. Therefore, goals that don’t contribute to the well-being of others feel less meaningful because they don’t align with your natural inclination to help others. Further, scientific research confirms that actively contributing to the well-being of others makes you happier: When you act with the intention of helping others, you activate the same parts of your brain that are stimulated by pleasurable activities such as eating good food or having great sex.)

4. It’s something you can make money doing. This provides opportunities for financial stability, allowing you to devote more time and energy to goal-related tasks and what you love doing. (Shortform note: While financial security is important, Ian Robertson (The Winner Effect) warns that introducing external rewards for activities you’re internally motivated to pursue can diminish your motivation over time. It does this by shifting your focus from the inherent satisfaction you feel while performing the activity to the external reward you’ll receive after you complete it. This change in perspective can transform a once-enjoyable pursuit into a chore. Therefore, maintain equal focus on the first three elements listed above to maintain your sense of satisfaction.)

Because your ikigai generates internal rewards, the process of working toward ikigai-based goals is as satisfying as achieving them. As a result, you always feel motivated to take action and make progress toward these goals.

Tips for Finding Your Ikigai

Raymond suggests that you can find your ikigai by ranking all your interests, skills, activities, and career ideas against each of the four elements we just outlined. For example, if one of your hobbies is upholstering furniture, you would rank this activity by asking yourself these four questions:

So, for the upholstering example, your questions might look like this:

- How much do I love upholstering?

- How good are my completed projects, and how willing am I to improve my skills?

- How much potential is there for my skills or upholstered furniture to benefit others?

- How much potential is there for my skills or upholstered furniture to make money?

Once you’ve ranked your interests and activities, identify anything that ranks highly in all four elements.

| Track How Your Activities Make You Feel If you’re struggling to think of potential interests or activities, try this complementary method for identifying fulfilling activities: Start a daily journal to track and reflect on how your activities make you feel. According to Bill Burnett and Dave Evans (Designing Your Life), this helps you identify what types of experiences make you feel joyful, engaged, and energized—and those that make you feel bored and drained. After the first week of tracking, include weekly reflections in your journal: Zoom in on the details of each activity to identify what you specifically like or dislike about it. Pay particular attention to who you were with, what you were doing, where you were, and what you were interacting with (for example, people, objects, or a machine) as your feelings rose and fell. Write down any themes, insights, or surprises you discover. If your current schedule doesn’t offer much in the way of variety, consider including reflections on past experiences that stand out as particularly positive or negative. |

Don’t feel discouraged if you don’t immediately discover your ikigai. Raymond explains that finding your ikigai is an evolutionary process—your feelings about different activities will naturally change as you grow and gain new experiences. He suggests completing this exercise periodically will help you understand your shifting priorities. Over time, this will provide opportunities to move toward internally rewarding activities.

| Make Short-Term Goals David Epstein (Range) echoes the idea that meaningful goals hinge on your willingness to continually evaluate and adapt to shifting priorities. He adds a practical way to put this into action: Plan for the short term instead of the long term. He argues that it’s better to pursue satisfying goals and opportunities in the short term than to commit to a single long-term goal or vision for two reasons: 1. You can’t predict how your needs will change: What satisfies you now may not satisfy you a few years from now. 2. You can’t predict how the world will change: It’s impossible to know what opportunities will or won’t be available in the future. Planning for the short term helps you easily adapt to these changes and take advantage of immediate opportunities, exposing you to even more satisfying experiences than you might encounter with a more long-term vision. |

Example: Japanese Takumis

In Japan, takumis are individuals who learn to flow with their ikigai as they become masters of a highly particular craft. The work of takumis displays a special kind of simplicity that combines sophistication and attention to detail in pursuit of their ikigai. Various industries employ them, from automobile makers to entertainment companies.

For example, in a Japanese town with several factories that produce makeup brushes for big-name companies. One Takumi had become an expert at choosing and sorting brush bristles. She was visibly happy and dedicated to her task, which she performed with amazing skill and grace, fully absorbed in the flow state. The company president told them that this takumi was one of the most important people in the company, because every brush bristle went through her. Takumis protect their space and make sure to create distraction-free environments that are conducive to entering the flow state. They are often reclusive by common standards, choosing to limit many

| Other Methods for Finding Your Ikigai Logotherapy: Logotherapy is unique among Western forms of psychotherapy because it focuses explicitly on helping people find meaning. Like ikigai, logotherapy says we don’t create our life’s meaning. Instead, we discover it. The formal practice of logotherapy takes place in five steps or stages: 1. Someone feels empty or anxious. 2. A therapist helps the person realize that her negative feelings are really the desire for a meaningful life. 3. The patient discovers her life’s purpose, relative to that moment in time. 4. The patient freely accepts that purpose. 5. With her newfound passion for life, the patient now overcomes her problems and sorrows. Morita Therapy: Another possible aid for finding your ikigai comes from Morita therapy, a Japanese form of life therapy specifically based on finding your purpose. Morita therapy teaches people in psychological crisis to accept their emotions instead of trying to control them. It says your emotions will automatically change when you change your actions, and as this happens, your purpose will become clear. The practice of Morita therapy takes place in four stages. The first stage is a week of absolute bed rest and total silence. This creates an extended space for doing nothing but watching your mind, thus clearing away the layers of manic mind activity that obscure your purpose. The second and third stages take the patient through a multi-stage reintroduction to active living and working. Activities include keeping a diary, practicing breathing exercises, walking, and doing chores, while still maintaining mostly silence so the patient can continue to reflect. The fourth stage has the patient return to the world and social life as a newly inner-directed person with a clear sense of purpose. The patient now knows who they are and what they’re supposed to do. |

Try These Ikigai Exercises

Why do you get up in the morning? What gives your life meaning and purpose?

Many people can’t answer these questions. Even worse, they’re stuck in dysfunctional lifestyles that prevent them from ever finding out what their purpose is. If that sounds like you, check out these ikigai exercises. They will help you reflect on what your personal ikigai might be and consider some possible avenues for realizing it in reality.

Exercise 1: Consider Your Ikigai

- How does the very concept of ikigai make you feel? Does it feel “right”? Does it make sense to you? Why or why not?

- Describe someone who has a strong ikigai. It could be someone you know personally or some famous person in history (an artist, athlete, inventor, or anyone else). What’s their ikigai? How can you tell?

- What do you think your ikigai is? (Remember, some people have more than one, so if that’s you, list them all.)

- If you don’t know your ikigai, why not? What’s standing in the way of you figuring out your purpose in life?

Exercise 2: Use Flow to Find Your Ikigai

Write down the activities that bring you into the flow state. (These are activities that engage you so deeply that time flies and you feel pleasurably focused, creative, and capable. They might be related to your job, hobbies, talents, interpersonal relationships, or any other factors.)

- Why do you think these particular activities create flow for you?

- What do these activities all have in common? What recurring themes do they involve?

- Go deeper: What ikigai (or ikigais) might lie behind your flow activities? What life purpose might these activities be driving you towards?

Learn More About Ikigai

If you want to learn even more about ikigai, we recommend checking out the full guides to the books mentioned in this article:

- Ikigai & Kaizen by Anthony Raymond

- Ikigai by Héctor García and Francesc Miralles