Do you want to speak up at work, leave a toxic situation, or simply stop taking the easy way out? We’ve curated nine approaches that will help you become the courageous person you want to be.

Discover how ordinary people develop extraordinary courage with insights from authors Chip Heath and Dan Heath (The Power of Moments), Mariann Edgar Budde (How We Learn to Be Brave), Brendon Burchard (High Performance Habits), and Robert Greene (The 48 Laws of Power).

Table of Contents

- #1: Prepare Yourself for Courage

- #2: Recognize the Courage You Already Have

- #3: Make Authentic Everyday Choices

- #4: Appreciate Hardship

- #5: Fight for Someone Else

- #6: Replace Hesitancy With Audacity

- #7: Develop the Virtues That Support Courage

- #8: Be Flexible and Practical in Your Approach to Courage

- #9: Navigate the Aftermath of Brave Choices

- Exercise: Reflect on Your Decisive Moments

- Learn More About Developing Courage

#1: Prepare Yourself for Courage

In their book The Power of Moments, Chip Heath and Dan Heath write that we feel a great deal of pride when we act with courage—when we stand up for someone else, call out injustice, or fight for something we believe in. These moments are meaningful because they show us what we’re made of. The problem with these moments is that it’s very difficult to engineer situations that call on us to be courageous—they almost always happen spontaneously. However, you can practice and prepare yourself mentally to act courageously when it’s necessary. The Heaths note that, while you might not have any control over when opportunities to act with courage appear, you do have control over how you react to these opportunities.

(Shortform note: In their book Switch, the Heaths put a name to this phenomenon of clamming up when faced with the task of making a choice—decision paralysis. When presented with numerous options or ambiguity, humans are predisposed to conserving their mental energy by defaulting to whatever decision feels easiest or most familiar, or not doing anything at all.)

Preloaded responses are reactions that you’ve drilled into your memory so that they’re immediately ready in a situation that calls for it. For example, “When I see Bill and his friends mocking my sister at school, I will walk over, ask them to stop, and walk her to class.” While thinking of your preloaded responses, it’s helpful to reframe your thoughts away from, “What is the right thing to do?” This question forces you to deliberate between all the different “right” responses you could have. Instead, ask, “How can I get the right thing done?” This question asserts that you know what’s right and now must make it happen. It’s not a matter of what you should do, but what you will do.

Example: Speaking Up About Inappropriate Remarks

Imagine that your colleague makes a racially insensitive remark to another colleague. Without any practice, you’d likely be so caught off-guard that you’d do nothing at all in response. However, what if you’d had a preloaded response at the ready? “I know that Mary makes insensitive jokes to her friends about Julie. That’s not right and it won’t stop unless I bring it to HR. The next time I hear her make a remark like that, I’ll say ‘Mary, that’s a really inappropriate and disrespectful thing to say, and as it goes against our company values, I’ll be reporting you to HR.’” Chances are, if you’d had this preloaded response prepared, you would have been primed to speak up the first time you heard your colleague making these types of remarks.

Preloaded Responses for Personal Moments of Courage

Asserting that you know the right thing to do and planning out how to make it happen can apply to smaller, very personal moments of courage as well. Doing the right thing and acting with integrity matters, even if you’re doing it just for yourself.

Perhaps you’re trying to cut down on drinking. The journey toward sobriety is full of situations that will call on your ability to do the right thing, and you can cut out the hesitation and temptation of these situations by creating preloaded responses.

First, remember to reframe your thoughts. You already know what the right thing to do is: avoiding situations that will tempt you to drink. Then, determine how you can do that. You identify your triggering scenarios and practice your actions: “When the waiter asks me what I would like to drink, I will say seltzer.” “When I am walking home after work, I will take the long way around the block to avoid walking in front of the bar.”

In practicing these small moments of courage so that you may put them into action, you can bring out your best self and multiply your opportunities for meaningful moments of personal pride.

| Try Creating Precommitments Preloaded responses are a type of precommitment—a pact you make with yourself about the way you’ll act in a certain situation. At times, rehearsing your preloaded response may not be a strong enough pact to prompt you to follow through. You can try raising the stakes by putting more tangible precommitments in place. In his book Indistractable, Nir Eyal outlines several ways you can use precommitments you can use to push yourself into doing the right thing. Create social pressure: This kind of pact, which Eyal calls an “effort pact,” is a precommitment that makes it harder to do something undesirable. One way you might use an effort pact is by making a precommitment with someone else—you’re not likely to break the precommitment because of the added pressure of being “watched” by someone else. For example, you might ask a friend to walk home from work with you every day so you don’t stop at the bar. Put your money on the line: In this pact, you attach money to your precommitment—if you break it, you lose the money. You might attach a $100 bill to your fridge and make a pact: If you buy beer, you have to burn the money. Each time you think of buying beer, the potential loss holds you back. Identify with your future self: Make a precommitment to the identity you want to have by consciously talking about yourself as someone who has that identity. For example, instead of saying, “I’m someone who’s trying to quit drinking,” you might say, “I’m someone who is quitting drinking.” |

#2: Recognize the Courage You Already Have

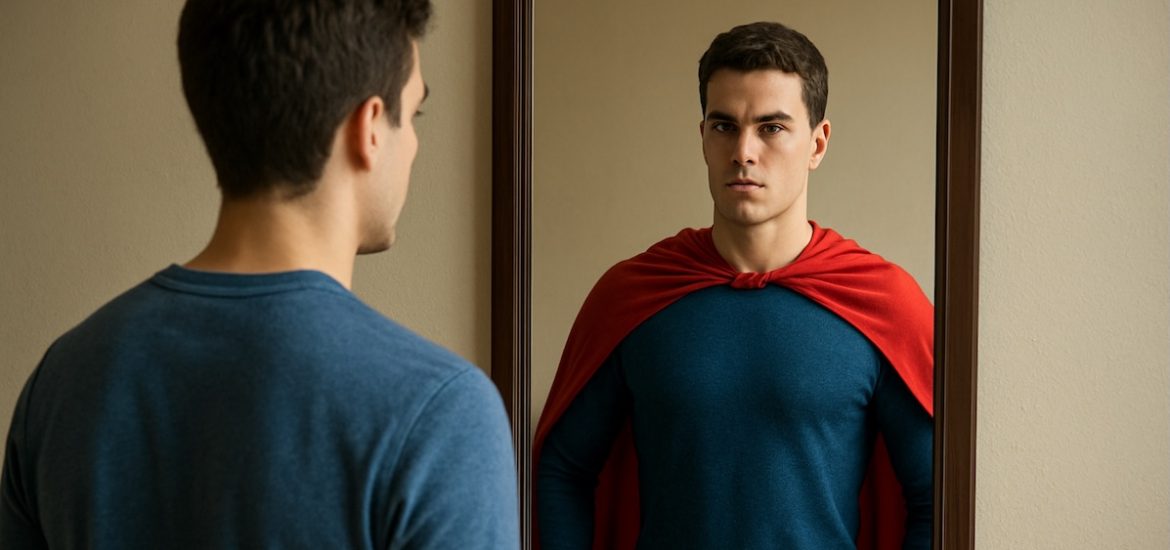

In her book How We Learn to Be Brave, Mariann Edgar Budde expresses her belief that we all already possess the raw materials for bravery. The problem isn’t that we lack courage: It’s that we often fail to recognize and access the courage we already have. The challenge is to recognize that this potential exists and to develop the awareness and skills to draw upon it when needed.

Part of this recognition involves acknowledging our vulnerabilities and limitations. Contrary to popular belief, courage doesn’t require fearlessness or perfect confidence. In fact, bravery often emerges when we acknowledge our doubts and proceed anyway. Understanding courage in this way—as a capacity we can develop rather than a trait we either have or lack—empowers us to approach occasions that call on us to be brave with greater confidence. Budde writes that we can learn to be brave—not by trying to transform ourselves into someone else—but by fully becoming who we already are.

#3: Make Authentic Everyday Choices

Budde challenges the myth that courage appears suddenly in those who possess it. Instead, bravery in decisive moments represents the culmination of smaller choices made over time. When a bishop confronts a president, a civil rights activist marches despite threats, or a parent supports their child’s difficult journey, these acts express values cultivated through countless earlier decisions.

This understanding transforms how we view courage. Rather than waiting for a dramatic moment to reveal our bravery, we can develop it through everyday choices that align with our values. Courage is learned through practice, meaning anyone can cultivate the ability to act bravely when it matters most.

| Building Courage Through Accumulation Budde’s insight that courage takes shape from many small choices challenges our perception of bravery as spontaneous. This process of accumulation reflects how we construct our identities continually over a lifetime through our interactions with our environment. Consider the decorator crab, a small sea creature that doesn’t have an innate method of camouflage but assembles its own disguise by collecting pieces of its environment—seaweed, sponges, coral, rocks, and other marine materials—and securing them to its shell. At first glance, this seems to be the opposite of courage. After all, camouflage is about blending in, not standing out. Yet the decorator crab’s strategy might illustrate a truth about courage: It emerges from the practical wisdom gained through countless small adaptations to our environment. When decorator crabs move to new locations on the ocean floor, they often shed their old decorations and collect new ones that reflect their new surroundings. Similarly, human courage develops through our responses to the specific challenges we face in the environments where we choose to spend our time. Some psychologists believe our values emerge as the “accumulated wealth of [our] aspirations”: the beliefs and commitments we collect and integrate into our identity. The decorator crab doesn’t randomly gather materials; it selects specific pieces that will help it survive in its particular environment. Similarly, the courage we develop throughout our lives is precisely shaped by the values, relationships, and environments that matter to us. In other words, we actively construct our bravery through countless small choices that reflect both the nature of our aspirations and the depth of our engagement with the world around us. |

Budde explains that, when a critical moment arrives, we rarely have time to deliberate. Instead, we respond based on the habits and values we’ve already developed. With consistent practice, courageous choices become more natural because each small act of bravery builds your capacity for integrity and courage. To strengthen your ability to be brave, Budde says:

- Pay closer attention to the small choices you face and what they say about your values.

- Identify patterns that connect situations where you tend to choose comfort over courage.

- Deliberately make the braver choice, even when it feels uncomfortable.

- Speak up when you witness something wrong.

- Take responsibility when you make mistakes.

- Embrace new challenges that stretch your abilities.

- Let go of grudges that hold you back.

- Be more honest and vulnerable with others.

- Learn from failures rather than avoiding them.

| Approaching Decisions Like a Zen Buddhist—or a Bayesian Statistician When Budde emphasizes that courage grows through small decisions, she touches on an idea that connects to both Eastern wisdom traditions and modern neuroscience. According to Zen Buddhism, making brave choices in ordinary moments isn’t just about building a habit—it’s about training ourselves to navigate uncertainty with greater wisdom. Instead of simply weighing pros and cons, mindful decision-making in the Zen tradition involves sitting quietly with choices as open questions. This creates space for intuitive wisdom to emerge alongside analytical thinking, creating a clearer picture of how to navigate uncertainty. The Zen Buddhist approach also aligns with discoveries about the decision-making process in our brains. Neuroscientists have learned that the brain has a remarkable ability to set aside existing biases when presented with new evidence. Rather than falling prey to confirmation bias (interpreting ambiguous evidence as supporting our current beliefs), our brains simultaneously consider multiple representations of reality. The brain weighs new information against our prior knowledge with what researchers describe as “an almost Bayesian-like, mathematical quality,” referencing a mathematical framework statisticians use to quantify uncertainty. Bayesian thinking addresses the essential question Budde raises: How do we modify our beliefs as we gain new information? Bayesian reasoning asks three questions: How confident are we in our initial belief? If our original belief is true, how likely would we be to observe the new evidence we’re seeing? Lastly, what is the probability of observing this evidence across all possible scenarios (not just the one where our original belief is true)? This process brings beliefs into alignment with reality, and, when applied to courage, suggests that each brave choice gives us new evidence about our capacity for courage. We gradually update our beliefs from “I am someone who avoid discomfort” to “I am capable of brave choices.” |

#4: Appreciate Hardship

In his book High Performance Habits, Brendon Burchard observes that many people are always searching for the “easy way” to do things. Whether it’s getting rich or getting fit, they don’t want to put in the work to achieve their goals—and they take the cowardly way out. Aversion to hardship prevents people from taking risks. Burchard argues that you must change your mindset on hardship if you want to build courage:

- Embrace the challenge. Learn to enjoy taking on and overcoming obstacles. This will help you change your hesitancy to excitement.

- Accept that difficult and unappealing tasks are essential to growth. There’s no “easy way” to everything in life. Remind yourself that the frustrating tasks you’re facing are helping you grow as a person.

- See the light at the end of the tunnel. Always remember that there are better times ahead. Remind yourself why you’re doing what you’re doing, and fight relentlessly toward your goal.

#5: Fight for Someone Else

Burchard asserts that overcoming obstacles for the benefit of someone you care about helps you cultivate courage. For example, if you want to provide for your child’s education, you might fight harder for a promotion or lucrative project. People are more inclined to go above and beyond for others than for themselves. For example, a woman might not challenge her boss who treats her poorly, but she’ll fight for her children if she sees them being bullied.

#6: Replace Hesitancy With Audacity

Law 28 of The 48 Laws of Power (Robert Greene) is “Enter action with boldness.” Greene writes that, if you hesitate before doing something, your doubts will undermine your efforts. When you act, do so boldly. And, if you make mistakes, correct them with even greater boldness. Everyone admires the bold. People have a natural tendency to hesitate before acting. You can overcome this tendency by practicing courage.

Greene argues that boldness doesn’t come naturally—it must be developed and practiced. He points to a few historical examples:

- Napoleon was originally timid and socially awkward, but he had to learn courage to succeed on the battlefield. Later, he applied it to all areas of his life, and it made him seem larger than life although he was physically small.

- When Columbus sought funding from the Spanish court for his voyage to the New World, he also boldly requested the title “Grand Admiral of the Ocean,” which was really a demand for respect. He received both.

- Pietro Aretino, a kitchen servant to a wealthy Roman family, had an ambition to be a great writer. Pope Leo X had received an elephant as a gift, and he was enthralled with it. He was so upset when the elephant died that he commissioned a painting to be put over the elephant’s tomb. Aretino saw an opportunity and wrote a satirical pamphlet purporting to be the elephant’s last will and testament, which ridiculed not only the pope but many cardinals, to whom the fictional elephant bequeathed various body parts. Readers immediately wanted to know who the audacious writer was. Even the pope was amused by his audacity and offered Aretino a job. Take opportunities to practice this kind of boldness.

Pitfalls of Boldness

This type of courage should be used tactically rather than willy-nilly to achieve specific goals. Greene cautions that you need to control and target it—not overdo it. Engaging in acts of erratic boldness is not the way to develop true courage. If you make it a pattern, you’ll offend too many people, which will cause your downfall.

Again, Greene offers an example from history. Lola Montez, mistress of the king of Bavaria, behaved so badly and inserted herself so boldly into the country’s affairs that she stirred outrage among the people—and the king deported her.

#7: Develop the Virtues That Support Courage

Budde contends that courage doesn’t develop in isolation but grows alongside other qualities that support it. She identifies several key virtues that create fertile ground for courage to flourish:

- Perseverance keeps us going when obstacles arise. Budde explains that while perseverance doesn’t have the drama of our initial brave choices, it’s essential for those choices to bear fruit. Without the ability to persist through difficulties, our brave beginnings often fizzle out when we face resistance.

- Acceptance means embracing reality as it is, including difficult circumstances we can’t change. Paradoxically, accepting what we can’t change creates space for meaningful action where we do have influence. It prevents us from wasting energy fighting reality and instead helps us adapt creatively.

- Faithfulness is about showing up consistently for our commitments and relationships, even when it’s difficult or our motivation is low. This steady dedication builds trust and integrity while creating stability in our lives and communities.

- Humility allows us to recognize both our strengths and limitations. It keeps us open to learning, receiving guidance, and growing from our mistakes. Humble courage strikes the right balance between confidence and openness.

- Self-awareness helps us understand our values, fears, and patterns of behavior. This understanding is crucial for making choices that align with our true selves rather than letting ourselves be driven by unconscious fears or external pressures.

To develop these supporting virtues, Budde says you should do the following:

- Set realistic goals, and celebrate small wins to build perseverance.

- Practice mindfulness to increase acceptance of your present reality.

- Establish routines that support the consistent fulfillment of your responsibilities.

- Seek feedback and mentorship to cultivate humility.

- Engage in regular reflection to deepen self-awareness.

- Surround yourself with role models who embody these virtues.

| From Aardvarks to Whales: Cultural Ideas of Courage Research on virtues across cultures reveals universal patterns and cultural variations in how different groups of people conceptualize virtues like courage and the traits that support it. A study examining virtues across 14 nations found that while some virtues (like honesty, respect, and kindness) appear to be nearly universal, others carry distinct value in specific cultural contexts. For instance, generosity is particularly valued in France, and certainty is uniquely important in Mexico. These cultural preferences reflect each society’s particular values and historical experiences. The qualities that support courage also vary culturally—as do the models we look to as illustrations of bravery. In many sub-Saharan African traditions, for example, the aardvark is considered a symbol of courage due to its willingness to tear down termite mounds despite facing hundreds of bites. The aardvark’s thick skin, which helps it endure these attacks, parallels Budde’s virtue of acceptance: the ability to embrace difficult circumstances with resilience and make the best of them. Some tribes even wear bracelets made from aardvark teeth as good luck charms, believing they impart courage and protection. Likewise, Nordic cultures have traditionally associated courage with perseverance through harsh conditions, whereas East Asian traditions often link courage to the virtuous restraint of one’s emotions. Within the Inuit communities of Alaska, courage is embedded in the relationship between humans and the natural world. Inuit whalers cultivate a deep, spiritual connection with bowhead whales, believing that respect, humility, and faithfulness are essential components of the courage humans need to hunt in dangerous conditions—and the bravery whales show by offering themselves up to the communities that rely on them for sustenance. The methods for cultivating the virtues that support courage also vary across cultures, with parallels to the practical approaches Budde recommends. Inuit traditions, for example, incorporate communal rituals and elder mentorship that align with Budde’s emphasis on surrounding oneself with virtuous role models. Similarly, sub-Saharan African storytelling serves as a form of reflection and mindfulness that reinforces courage-supporting virtues. While the specific practices may differ, what remains consistent is that courage rarely develops in isolation—it requires a foundation of complementary virtues that prepare us to act with integrity when decisive moments arrive. |

#8: Be Flexible and Practical in Your Approach to Courage

Life presents us with various situations that call for courage, and each type requires a somewhat different approach. By understanding these different scenarios, you can respond with the right kind of courage when they arise. Budde offers guidance for handling five common scenarios that demand bravery:

- When it’s time to go: Sometimes courage means leaving—a situation, relationship, or commitment that no longer serves your highest purpose. This requires facing uncertainty and the discomfort of new beginnings. Budde advises careful decision-making rather than an impulsive reaction, honoring what has been while embracing what could be, taking responsibility for your departure’s impact, and facing the unknown with hope.

- When it’s right to stay: While leaving often seems like the brave choice, sometimes the greater courage lies in remaining where you are and going deeper. This means recognizing when your work is unfinished and embracing the challenges of constancy rather than seeking escape. Budde encourages “leaning into” your current life, finding meaning in daily faithfulness, and discovering growth opportunities within existing commitments.

- When you need to start something new: Beginning a new venture requires a kind of courage that combines vision, initiative, and willingness to risk failure. Budde suggests moving forward despite uncertainty, being willing to adapt as you go, accepting imperfection as part of the process, and remaining open to unexpected directions.

- When you face circumstances you didn’t choose: Some of life’s most significant growth comes through difficult situations we didn’t ask for. Finding courage in these moments involves practicing radical acceptance, staying present rather than escaping through denial, treating yourself with compassion, and sharing your authentic experience with people you trust.

- When you’re called to step up: When opportunities align with your strengths, courage means embracing them with the appropriate amount of confidence. This involves recognizing your capacities, balancing confidence with humility, approaching challenges with enthusiasm, and maintaining a growth mindset.

| Courage Across the Centuries: Virginia Woolf’s Orlando Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando follows its protagonist through an extraordinary 300-year lifespan during which Orlando transforms from a man into a woman, experiences multiple historical eras, and faces numerous pivotal decisions that illustrate the varied types of courage Budde identifies—from deciding to go or stay, to starting something new, accepting difficult circumstances, and stepping up to opportunities. Through Orlando’s experiences across centuries (and genders), we can see how these different forms of bravery manifest in a single life, albeit an extraordinary one. The courage to go is central to Orlando’s early adventures, as the young nobleman leaves England to serve as ambassador to Constantinople, embracing uncertainty and new experiences with enthusiasm. Later, after transforming into a woman, Orlando demonstrates the courage to stay when she returns to her ancestral home despite the societal constraints placed on women, choosing to deepen her connection to her literary work and her land rather than seeking escape. Throughout the centuries, Orlando repeatedly shows the courage to start something new—whether embarking on literary endeavors, adapting to new historical eras, or rebuilding her identity after gender transformation. Perhaps most strikingly, Orlando embodies the courage to accept circumstances beyond our control. When Orlando awakens as a woman after a week-long trance, she accepts this profound change with remarkable equanimity. This acceptance of a dramatic, uninvited transformation illustrates Budde’s principle that some of life’s most significant growth comes through circumstances we didn’t choose. But what makes Orlando particularly relevant to Budde’s framework is how the character integrates these brave decisions into their identity over time. The long timeline of Orlando’s life allows readers to witness how decisive moments accumulate to form a coherent and consistent sense of self. |

#9: Navigate the Aftermath of Brave Choices

Budde writes that making a brave choice isn’t the end of the story—what happens afterward is just as important. By thoughtfully navigating what comes after making brave choices, you build a sustainable practice of courage that can serve you throughout your life. She highlights two crucial aspects of the aftermath of significant decisions that require ongoing courage:

The emotional letdown: After a significant brave choice, many people experience what Budde describes as an emotional letdown: a swing from their initial euphoria to doubt, emptiness, or even depression. This letdown can make you question whether your decision was right, but understanding that this reaction is normal helps you avoid being derailed by it. To navigate this phase, Budde recommends:

- Anticipating the letdown rather than being surprised by it.

- Staying connected to your original reasons for making the brave choice.

- Resisting the temptation to either retreat from your decision or overextend yourself.

- Allowing time for the significance of your choice to sink in.

- Leaning on supportive people during this vulnerable time.

- Being patient with yourself through the process.

Integration into your identity: For courage to become a sustainable part of your life, brave decisions need to be incorporated into your sense of who you are, rather than remaining isolated events. This integration transforms momentary acts of courage into a courageous way of being. To help with this integration, Budde suggests:

- Reflecting regularly on your decisive moments and what they reveal about your values.

- Allowing your personal story to evolve based on the courage you’ve demonstrated.

- Sharing your experiences with people you trust who can help you process their meaning.

- Applying insights from past experiences to future challenges.

| Release, Receive, Return: The Labyrinth Model for Life After Brave Decisions The post-courage letdown that Budde identifies isn’t a sign of failure—it’s a normal psychological pattern. The “arrival fallacy” describes our tendency to believe that achieving a goal will bring lasting happiness, only to discover that the joy is fleeting or absent entirely. Psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar, who coined the term, explains that we often overestimate how happy future achievements will make us, leading to disappointment when reality doesn’t match our expectations. After the initial rush of achievement subsides, we typically return to our emotional baseline, sometimes feeling even emptier than before because the promise of permanent happiness remains unfulfilled. Budde’s advice for navigating this letdown aligns with psychological research on the arrival fallacy. Budde and psychologists both emphasize staying grounded in your original purpose for making the brave choice, resisting the temptation to think the temporary happiness isn’t worth all the trouble, and allowing yourself time to reflect on your choices. Psychologists add additional strategies: setting multiple concurrent goals rather than fixating on a single achievement, finding joy in the process rather than just the outcome, and prioritizing relationships, which research shows is the strongest predictor of lasting happiness. The Episcopal tradition offers a tool for mindfully integrating our experiences into our lives: the labyrinth. Unlike a maze designed to confuse, a labyrinth offers a single path leading to the center and back out again—similar to the journey we take through decisive moments. Walking a labyrinth involves three phases that parallel the process of navigating courage’s aftermath: releasing (letting go of expectations and distractions), receiving (remaining open to insights at the center), and returning (integrating what you’ve learned as you follow the path outward). Many Episcopal churches maintain labyrinths as meditation tools, describing them as a way for us to learn to see “the wider pattern of our lives.” Whether physical or metaphorical, the labyrinth reminds us that the journey matters as much as the destination, and that integration—not just achievement—is essential for growth. |

Exercise: Reflect on Your Decisive Moments

In her book, Budde emphasizes that courage develops through our responses to decisive moments: turning points when we make conscious choices. Reflecting on past decisive moments in your life can help you recognize patterns in your courage development and prepare for future opportunities to be brave.

- Think of a time when you faced a decisive moment that required courage. This could be deciding to go in a new direction, staying committed to a difficult path, starting something new, accepting challenging circumstances, or stepping up to an unexpected opportunity. Briefly describe the situation and the choice you made.

- What values or beliefs guided your decision in that moment? How did this decisive moment reveal what matters to you the most?

- Looking back, what smaller decisions or habits had prepared you to respond with courage in that moment?

- How did this experience change you? Did it affect how you see yourself or approach subsequent challenges?

Learn More About Developing Courage

To better understand the cultivation and practice of courage in a broader context, take a look at Shortform’s guides to the books we’ve referenced in this article:

- How We Learn to Be Brave by Mariann Edgar Budde

- The Power of Moments by Chip Heath and Dan Heath

- High Performance Habits by Brendon Burchard

- The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene